Many mixed signals

The President and Vice President have this week sent mixed and confusing signals on the macroeconomic picture. It is hard to reconcile a “stay the course” strategy with (a) new bad data, (b) “we misread the economy” and (c) “we had incomplete information.”

This seems to be part of a broader problem with the Administration’s ability to send clear, coordinated, and internally consistent signals on economic policy.

I want to distinguish between my views on sound policy and the communications critique I present here. As an example, I oppose the House-passed climate change bill. But that is independent of my critique below that the President is making an absurd claim to sell that bill. There is a more intellectually valid case he could make for a bill that I oppose. I was skeptical but open to a successful PPIP, but the Administration oversold an underdeveloped policy.

A certain amount of confusion is normal, especially in a rapidly-changing economic and market environment. But events are not driving changes on a daily basis as they did last Fall. Instead, this confusion is being driven by deliberate policy signals from senior Administration officials.

Macroeconomy and stimulus

- More important than any question about a second stimulus, a reporter should ask the Administration if they think the economy is right now getting weaker or stronger. Before last Friday, I’m confident they would have said something like, “It’s slowly getting stronger, but it will take time.” Last Thursday’s jobs rport creates uncertainty around this answer. It’s a crucial judgment for the Administration to make, and an important signal to send. For now the Administration is signaling that it thinks the economy continues to strengthen, while admitting that their initial forecast was overly optimistic, and while confronting an important jobs report last week that moved in the wrong direction.

- The Administration argues the stimulus is working to improve the economy now. Their “create or save” metric, however, makes it impossible to prove this, so they must rely on demonstrating that cash is actually flowing out the door, and showing particular examples of new jobs resulting from that spending. It’s hard to convince people that jobs are being created when they see on net that hundreds of thousands of jobs are being lost each month. And so little of the stimulus cash has flowed so far that their argument that the stimulus is helping now is incredible.

The budget

- The President and his Budget Director Peter Orszag say that the President’s budget would cut the deficit in half, yet Director Orszag argues elsewhere that the deficit measure they use in that calculation is the wrong one.

- The President and Director Orszag say their budget reduces future deficits by $2 trillion over the next decade. CBO says it would increase deficits by $4.8 trillion, and that debt held by the public would exceed 82% at the end of the decade, a level not seen since the end of World War II. The Administration gets its result in part by using a “current policy” spending baseline, even though Director Orszag used on a more rigorous “current law” baseline while at CBO.

- The President and Director Orszag say that health care spending is the primary long-term budget problem. But CBO correctly says that the aging of the population, and its effects on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid spending, is a bigger and more immediate problem than health care cost growth 40+ years from now.

- The President and Director Orszag say their health care proposals would slow the growth of long-term public and private health care spending. CBO says the legislation being developed in Congress would significantly increase government health care spending, and that the long-term changes don’t produce scorable savings. Director Orszag claims this means that CBO agrees with him that these proposals will save money, but just won’t attach a number to it. And yet the Director, who has hundreds of analysts working for him, has not produced his own numbers to measure the long-term savings from health care reform.

Climate change

- The President and his team make the Orwellian argument that cap-and-trade legislation that would raise the price of energy is good for the economy. If they want to argue that the long-term climate benefits are worth the economic costs, that’s a debatable argument. it is absurd to claim that higher energy prices will help the U.S. economy by creating “green jobs.”

TARP

- With great fanfare the Administration rolled out its new and improved TARP plan this Spring, including stress tests, a new foreclosure mitigation plan, and a Public-Private Investment Partnership to buy toxic financial assets. PPIP is now on life support, and we have not yet seen from the Administration any evidence that the foreclosure mitigation plan is working. Aside from the apparently successful stress tests, the new TARP plan for banks looks a lot like the old TARP plan for banks.

The Vice President’s and President’s recent macro/stimulus comments were so provocative that it is unsurprising they are driving intense press scrutiny. There are many other claims that the Administration has made that would collapse under rigorous questioning, and that send mixed signals to investors, Congress, the press, and the public. I will continue to wait for this rigorous questioning from a largely docile and pliant press corps.

(photo credit: February 20, 2009 – Stop Go by Davery B.)

Scrambling for a macroeconomic message

Provoked by the Vice President’s comment on Sunday that the Administration “misread the economy,” the Obama Administration is partway through an unplanned shift in their topline economic message. It is painful to see this transition play out in public as the Obama Administration and its allies try to find their footing on the most basic questions about the U.S. economy and their macroeconomic policy.

Last Thursday the President spoke in the Rose Garden after meeting with some alternative energy CEOs. His statement included only a placeholder about the jobs report:

And obviously, this is a timely discussion, on a day of sobering news. The job figures released this morning show that we lost 467,000 jobs last month. And while the average loss of about 400,000 jobs per month this quarter is less devastating than the 700,000 per month that we lost in the previous quarter, and while there are continuing signs that the recession is slowing, obviously this is little comfort to all those Americans who’ve lost their jobs.

There’s no real substance there, so last Thursday the Administration’s basic economic message appeared unchanged by the new jobs data.

Then on Sunday, when asked about why unemployment is now higher than the Administration predicted it would be, the Vice President said:

The truth is, we and everyone misread the economy. The figures we worked off of in January were the consensus figures and most of the blue chip indexes out there.

… And so the truth is, there was a misreading of just how bad an economy we inherited.

In Moscow yesterday, the President tried to correct the Vice President:

THE PRESIDENT (to NBC): No, no, no, no, no. Rather than say “misread,” we had incomplete information.

THE PRESIDENT (to ABC): There’s nothing that we would have done differently.

THE PRESIDENT (to Fox News): I think it’s important to understand that we’ve got a short-term challenge which, no matter how big our stimulus was, was going to be a challenge … partly because we’ve got fiscal constraints. … You just can’t push that out that quickly, partly, not just because the federal government has to process applications, but also because states and local governments have to gear up to get these projects going. … I don’t take anything off the table when unemployment is close to 10 percent and a lot of Americans are hurting out there.

NEC Director Dr. Larry Summers said Tuesday:

It is clear from the data that there needs to be more fiscal stimulus in the second half of the year than there was in the first half of the year. Fortunately, the stimulus program designed by the president and passed by Congress provides exactly that.

The Vice President’s economic advisor, Dr. Jared Bernstein, said:

It’s working, it’s demonstrably working. … There is no conceivable stimulus package on the face of this earth that would fully offset the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs said today in a press gaggle on Air Force One en route to Rome:

Q I know I might get crosswise with you on this, but is the White House considering a second stimulus?

MR. GIBBS: Well, I would say — I’ll repeat what I’ve said and I think the President and Vice President have said, and I think the President said this yesterday, he’s not ruling anything out, but at the same time he’s not ruling anything in. Obviously we passed a hefty recovery plan that implements over the course of about a two-year period of time, and we’re on track with that implementation.

The Gibbs statement was reinforced by an emailed statement from one of his deputies, Jen Psaki:

We remain focused on putting thousands of Americans back to work through the implementation of the recovery act and any discussion of a second stimulus is premature at this point.

These comments lead me to conclude that the Administration’s policy is unchanged: their answer on a second stimulus is “No for now,” while reserving the right to change their minds later as new data comes in.

This answer is, however, being lost on some of their friends and allies:

Dr. Laura Tyson, characterized as “an outside adviser to President Barack Obama” said:

The stimulus is performing close to expectations but not in timing. … The stimulus was a bit too small. (Source: Bloomberg)

and

We should be planning on a contingency basis for a second round of stimulus. (Source: NBC)

Here’s House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer:

We need to be open to whether or not we need additional action.

And here is Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid:

As far as I’m concerned, there’s no showing to me that another stimulus is needed. Things are … things, as Bernanke said, the crops have been planted, the shoots are now appearing above the ground. And that certainly is evident based on the fact that slightly over 10 percent of the dollars are out among the people.

It’s hard to reconcile a “stay the course” strategy with (a) new bad data, (b) “we misread the economy” and (c) “we had incomplete information.”

Last week’s jobs report provoked this chaos. For the first five months, the Administration’s macroeconomic message was simple and internally consistent:

<

ul>

I disagree with several of these points, but this is/was their message.

Until last Thursday, the employment data was consistent with this message, and in particular with “Things are getting better bit by bit.” The economy lost fewer jobs in March than in February, fewer still in April, and even fewer in May. A topline message of “Things are still bad and we feel your pain, but they’re getting better” was consistent with the most fundamental monthly metric of the country’s economic health.

Last week’s employment report fouled up this message. June’s job losses were significantly worse than May’s.

This data point is significant and poses a challenge to the President and his team. If it is the beginning of a new downward trend, then both the Administration’s stimulus policy and their message about the economy and economic policy need to change. If, however, it is a random deviation from the previous trend, then the old policy and message still works, and they’ll just have to ride out the next few weeks until new data confirms that things are actually still on a gradual upward trend.

Monthly employment data has large “error bars.” For a while, the standard joke among our CEA economists was that the forecast for the upcoming monthly jobs report was +50,000 jobs, plus or minus 100,000. There’s a decent chance that the June employment report was just a bad luck data point (although the report was consistently bad throughout, which is scary).

Thus the President, aided by his advisors, has to make a macroeconomic judgment and a a policy decision: Does Thursday’s jobs report necessitate a change in policy now, or should we stick with our policy and wait for additional data to see if it confirms a new downward trend? This economic judgment and policy decision should then drive their public messages to the press, markets, and Congress. Within the White House, I imagine this judgment call is primarily a Summers/Romer responsibility, supplemented by views from Treasury Secretary Geithner, Budget Director Orszag, and Labor Secretary Solis.

For the time being, the Administration and its allies are implicitly wagering that the new jobs report is not an early warning sign of a new downward trend. They are sticking to their existing policy and message.

I see at least five challenges on the path they have chosen:

- It might be wrong. If the July employment report (to be released August 7th) is worse than the June report, the Obama team will look like they have missed a turning point. In their preemptive defense, it’s often quite difficult to identify turning points.

- The Vice President’s comment that “we misread the economy,” followed by the President’s comment that “we had incomplete information,” undermines confidence in the Administration’s ability to diagnose and address major macroeconomic trends. Sticking with the current path under potentially changed circumstances risks reinforcing this feeling.

- They have to rally nervous allies to echo their message that “the stimulus is working,” while the evidence to prove this is in question. Just as it’s impossible for opponents to prove that the stimulus did not “save or create” jobs, it’s impossible for the Administration to demonstrate that 467,000 lost jobs is better than it would have been without the stimulus. On a raw political level, how do you convince people that the stimulus is working when the economy is still in visible decline?

- They have to publish the Mid-Session Review of the President’s Budget this month, with a new updated economic forecast. That forecast was almost certainly locked down weeks ago. Do they revise it downward based on last week’s bad jobs data? Either choice has significant downsides.

- They have to combat a press trend for a “weakening U.S. economy” storyline to overwhelm their desire to move health care legislation through the Congress in July. This storyline has exploded today in the Washington-centric press.

I conclude with two quotes that crystallize the Administration’s current challenge. The first is from a good analysis by Dan Balz in today’s Washington Post:

It seems hard to square an assessment that the administration underestimated the severity of the recession and the assertion that the White House wouldn’t have done anything differently had it known how bad things really were.

And since this is a debate about Keynesian macroeconomic fiscal stimulus, here is how John Maynard Keynes replied to a criticism during the Great Depression of having changed his mind on monetary policy:

When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?

(photo credit: humpty dumpty sat on a wall by paul peracchia)

Six month economic policy status update

We’re less than two weeks away from the six month mark of the Obama Administration. Here is a summary I would give to someone who had missed the past six months. I think the groupings are particularly important.

Good

- The bank stress tests worked – regulators now have a common framework to evaluate the health of the 20 largest banks, and these banks are in the process of raising private capital.

- Reports are that the Fed’s Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) is working, providing liquidity to certain markets that lacked it.

- There has not been a sudden failure of a major financial institution since the President took office, in part due to significant new government efforts with AIG and Citigroup, and an ongoing flow of hundreds of billions of dollars to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

- As a result, the severe instability that plagued inter-bank lending markets and certain credit markets last fall and winter has largely receded.

Bad

- As the Vice President said on Sunday, the Administration underestimated the severity of short-term macroeconomic decline.

- The U.S. economy has lost 2.64 million jobs since the beginning of the Administration, and the unemployment rate is now 9.5%. Most private sector forecasters project economic growth will turn positive in the fourth quarter of this year, with job growth to resume sometime in 2010. The June job report was really bad. Watch the July report closely.

- The stimulus was poorly designed by Congress, such that it is not now having any measurable economic effect, and the bulk of the GDP boost won’t come until 2010. When you combine this with the missed economic forecast, it means the next six months will be worse than they needed to be.

- The President’s budget would result in massive increases in both deficits and taxes, driving by significant proposed spending increases, especially in health care. CBO projects deficits over the next decade equal to 5.2% of GDP, more than double the cumulative deficit projected under current law. Debt held by the public would rise from 57% of GDP in 2009 to 82% of GDP by 2019, while taxes would grow from 15.5% of GDP in 2009 to almost 20% by 2019.

Too soon to tell

<

ul>

Non-existent

- The much-hyped plan to buy troubled/bad/legacy/toxic assets from financial institutions, aka the Public-Private Investment Partnerships (PPIP), is reportedly being dramatically dialed back, almost to non-existence. This means that the Obama Administration’s much-hyped “new way” of doing TARP is basically the old way + the stress tests. After all the bashing of Secretary Paulson and the Bush Administration, TARP’s application to banks looks quite similar to how it looked in December and January.

- The same CBO table shows no spending so far for the President’s small business lending program. I can’t tell if it’s in operation or not.

- There has been almost complete radio silence on trade and open investment. The Free Trade Agreements with Colombia and South Korea are on life support due to Presidential and Congressional inaction. The Buy America provisions in the stimulus law are protectionist.

- The President’s budget and Congressional proposals would significantly increase federal health care spending by creating a new entitlement to health insurance. The President and his advisors emphasize that their long-run budget plan is to “bend the health cost curve downward” by making systemic policy changes that would slow the growth of private and public health care spending. While the Administration has proposed policy changes that would increase the information available to consumers of health care, they remain silent on how to change the incentives to use more and more expensive health care. As a result, the President has no proposals that will slow the long-run unsustainable growth of private health care spending, and the Administration’s promises of long-run budget discipline are unsubstantiated.

- Similarly, the Administration emphasizes the long-run budgetary effects of health care cost growth, but the Administration has no policies to address the more immediate budget pressures driven by an aging population.

Uncertain and unlikely

- Climate change legislation passed the House June 26, but is unlikely to pass the Senate this year or next.

Uncertain

- Health care reform legislation will pass the House, probably in July. Prospects in the Senate are highly uncertain. If legislation moves in the Senate, it will not be until fall.

- The fate of the President’s financial regulatory reform package is unclear. House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank is talking positively about moving at least part of the package this Fall. Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd is busy with health care reform and his re-election campaign. I think it is unlikely legislation will be enacted this year. If something is enacted, it will only be a piece of the whole.

Observations

Each of the good items is a joint Treasury-Fed operation.

In my judgment, four initiatives that the Administration hyped heavily appear dead or nearly dead: PPIP, foreclosure prevention, small business lending, and climate change. I respect that others may disagree with this judgment.

There is almost complete radio silence from the Administration on international economic policy, while incremental protectionist measures quietly move into place.

I think that over the next 3-6 months, the President’s economic stewardship will be judged almost entirely on (1) how he deals with the worsening macro picture, and (2) whether he signs into law a health care reform bill that meets his goals. Both are fraught with peril.

Misreading the economy

Here’s Vice President Biden yesterday on This Week with George Stephanopolous:

STEPHANOPOULOS: While we’ve been here, some pretty grim job numbers back at home — 9.5 percent unemployment in June, the worst numbers in 26 years.

How do you explain that? Because when the president and you all were selling the stimulus package, you predicted at the beginning that, to get this package in place, unemployment will peak at about 8 percent. So, either you misread the economy, or the stimulus package is too slow and to small.

BIDEN: The truth is, we and everyone else misread the economy. The figures we worked off of in January were the consensus figures and most of the blue chip indexes out there.

Everyone thought at that stage — everyone — the bulk of…

STEPHANOPOULOS: CBO would say a little bit higher.

BIDEN: A little bit, but they’re all in the same range. No one was talking about that we would be moving towards — we’re worried about 10.5 percent, it will be 9.5 percent at this point.

STEPHANOPOULOS: But we’re looking at 10 now, aren’t we?

BIDEN: No. Well, look, we’re much too high. We’re at 9 — what, 9.5 right now?

STEPHANOPOULOS: 9.5.

BIDEN: And so the truth is, there was a misreading of just how bad an economy we inherited. Now, that doesn’t — I’m not — it’s now our responsibility. So the second question becomes, did the economic package we put in place, including the Recovery Act, is it the right package given the circumstances we’re in? And we believe it is the right package given the circumstances we’re in.

We misread how bad the economy was, but we are now only about 120 days into the recovery package. The truth of the matter was, no one anticipated, no one expected that that recovery package would in fact be in a position at this point of having to distribute the bulk of money.

The Vice President says that “we and everyone else misread the economy,” and that “no one anticipated, no one expected that that recovery package would in fact be in a position at this point of having to distribute the bulk of money.”

This is inaccurate. On January 10, 2009, Dr. Christina Romer and Dr. Jared Bernstein published a paper titled The Job Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Plan. Dr. Romer is now Chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, and Dr. Bernstein is now the Vice President’s chief economic advisor. This is the paper that was used as the basis for the President’s and Vice President’s arguments for the stimulus. Here is footnote 1 from that paper (it’s in the endnotes on page 14):

1) Forecasts of the unemployment rate without the recovery plan vary substantially. Some private forecasters anticipate unemployment rates as high as 11% in the absence of action.

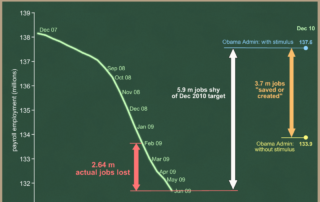

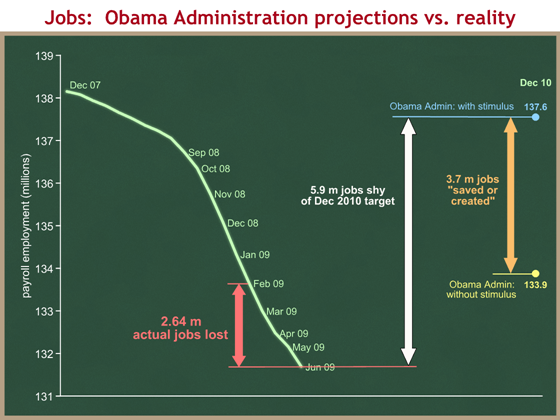

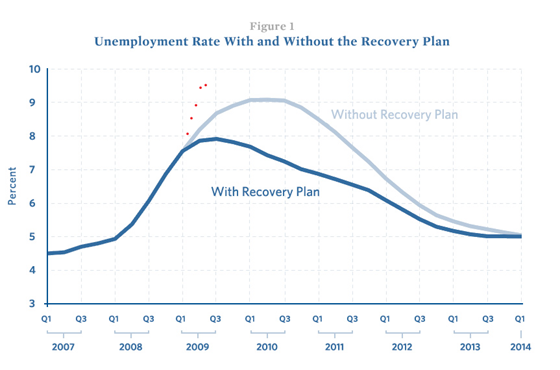

This graph from the Administration’s paper illustrates how much worse things are than was predicted. The blue lines show the unemployment rate predictions from the Romer-Bernstein paper, while the red dots are the actuals since the President took office:

You can see that the unemployment rate is significantly higher now than the Administration projected it would be without a stimulus.

You can see that the unemployment rate is significantly higher now than the Administration projected it would be without a stimulus.

The Vice President is, in effect, arguing that we now know that the light blue “without stimulus” line was much higher than they had originally thought, and that the red dots of actual employment represent an improvement from that correct “without stimulus” line. If he thinks the stimulus is now having a measurable effect (I don’t), then he is arguing that the light blue line should be above the red dots.

I agree with the Vice President that they misestimated where the light blue line would be. In addition, I think the stimulus is having no measurable effect on the U.S. economy right now. The stimulus law was pooly designed so that the bulk of the economic effect does not occur until 2010.

In terms of the graph, I think the Administration overestimated the gap between the light blue and dark blue lines throughout 2009. I think the dark blue line should pretty much match the light blue line (wherever that light blue line might be) up until the fourth quarter of this year.

I think the Vice President would say that, were they recreating this graph today with new information, they would put the light blue line above the red dots, and the dark blue line would match the red dots. In contrast, I would argue that both the light and dark blue lines match the red dots, and will continue to do so for several more months. Beginning in the fourth quarter of this year, the stimulus will start to have a significant effect, and the dark blue line will drop below the light blue line. Of course, since we have no way of knowing where the real light blue line would be, it’s impossible to prove.

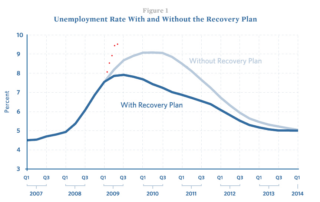

The above graph shows the unemployment rate: what share of the population is actively looking for work and not finding it. I have made a similar graph that compares the Administration’s January 10 projection of employment levels with reality, how many people are actually working. Since Dr. Romer and Dr. Bernstein did not create a graph like the one they did for the unemployment rate, we can only compare reality now against what they projected for the end of 2010, but it is still useful to see the gaps.

(Sources: BLS for actuals and here, Romer/Bernstein paper for projections)

There’s a lot here, so I will walk you through it step by step. The green line shows how many millions of people are employed in the United States, based on the payroll survey. When you heard last Thursday that the U.S. economy lost 467,000 jobs in June, that’s the drop on this graph from May 09 to June 09.

I have started counting actuals for President Obama with the February 09 jobs report, which came out on March 6. The red arrows show that a net 2.64 million jobs have been lost in the U.S. economy since President Obama took office. I’m being slightly generous in that jobs lost in the President’s first 10 days in office are not counted in this total. Also, I’m starting the graph at the all-time peak of employment in December 2007, when NBER designated the beginning of the recession. Had I begun this graph in January of 2009, the visuals would have looked worse, but I think this is a fairer presentation.

On the right we have the Administration’s projections from the January 10 Romer/Bernstein paper (Table 1 on page 5). They projected that if the stimulus were not enacted, there would be 133.9 million people employed in the fourth quarter of 2010 (the yellow dot). They projected their proposal would “save or create” 3.7 million jobs by that time (the orange arrow), and they projected a post-stimulus employment level in the fourth quarter of 2010 of 137.6 million people (the blue dot). In both cases I’m assigning December 2010 to “Q4 2010.” In doing so I’m giving the Obama team until the end of the quarter to allow a little more time for job growth.

For the Administration’s original projection to be correct, the U.S. economy will have to create a net 5.9 million jobs between now and December 2010.

This graph demonstrates why the “created or saved” metric is so dangerous. It’s the delta between two projected figures. Projecting both ends of the orange arrow allows the person doing the estimate to have a tremendous amount of control over the size of the arrow, and thus over the projected number of jobs “saved or created.” This is why some people have criticized the Administration’s use of this measure.

Yesterday the Vice President implicitly argued that the Administration’s mistake in January was not in estimating the size of the orange arrow, but the level of the yellow dot, the forecast for where the economy would be without a stimulus.

The President and Vice President routinely claimed that the stimulus would “create or save” 3.5 million jobs. The above graph shows that is a projection of the change in the level of employment for the fourth quarter of 2010. I have never heard them say that the same paper projected that the stimulus would “create or save” 2.2 million jobs by the fourth quarter of 2009. While this number is easily calculated from the Romer/Bernstein paper, the Administration apparently chose not to emphasize it in the President’s and Vice President’s remarks.

For those interested in replicating this calculation, I calculated this by multiplying the “2009 Q4” column of Table 3 by the “Total Effect” column in Table 2, and then summing the totals.

Tip for reporters: Ask the Administration if, given their misreading of the economy, they still hold to their January projection of 3.7 million jobs “saved or created” by the fourth quarter of 2010. I expect they will say yes, their estimate of the effects of the stimulus has not changed, only their estimate of the baseline from which those effects are calculated. If they do, ask if they still hold to the projection in that same report of 2.2 million jobs “saved or created” by the end of this year.

(photo credit: whitehouse.gov)

CNBC today at 2 PM

I’ll be on CNBC once, maybe twice, in the 2 PM EDT hour today. I expect to talk about today’s employment report, maybe toward the top of the hour. They may also have me comment on the President’s Rose Garden remarks, which are expected sometime in the 2 — 2:30 PM range.

The New York Times (implicitly) calls for no climate change law

The House passed the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill last Friday on a largely party-line 219-212 vote. The New York Times editorial board now urges the Senate both to strengthen and pass the House-passed bill. But the Senate is right of the House on climate, so the choice will be to strengthen or pass a bill. Senate passage would require “weakening” the bill from the standpoint of a cap-and-trade advocate. This legislative situation provides me with a great teaching opportunity about the hard choices of practical legislating.

As a reminder, there were two important Senate climate change votes in April on the Senate budget resolution:

<

ul>

The specifics of these amendments are less important than that Democrats split 27-28 (with 3 not voting) and 13-44 (with 1 not voting) on these amendments. (I am counting Independent Senators Lieberman and Sanders as Democrats.) This signals a deep split within the Senate Democratic caucus, rather than a few wayward moderates whom Senator Reid and the White House need to work. Most vote counters put solid Senate support for a carbon cap in the mid-40s. That is a long way from the 60 votes that advocates will need.

I believe the political popularity of cap-and-trade legislation has been overstated by advocates. It is easier to vote yes on the general question, “Do you want to do something bold to address climate change?” than on the specific question, “Do you support the House-passed bill, which would have the following specific costs [list the costs]?” To borrow a metaphor from a knowledgeable Senate insider (used in another context), “Everyone likes ice cream; not everyone likes rum raisin ice cream.” I expect some Democratic Senators will argue that they are open to pricing carbon but oppose this specific bill. And I believe they have strength in sufficient numbers to resist pressure from their leaders or the White House.

I think it is highly unlikely the Senate will pass any cap-and-trade bill before the end of 2010, but the only bill that would have a chance of passage would be one that would move in the opposite direction from that desired by the New York Times editorial page. The New York Times editorial board admits this:

The Senate will not be an easy sell. It has rejected less ambitious climate bills before. While 60 filibuster-proof votes are needed, only 45 Senators mostly Democrats, can be counted as yes or probably yes. There are 23 fence-sitters and very little Republican support.

If I am right, then cap-and-trade advocates inside and outside of government face a tradeoff: how much substance are they willing to sacrifice for the sake of legislative progress? The New York Times editorial board makes their judgment call:

Democratic leaders should nevertheless resist calls to weaken the targets on emissions reductions. The House bill is itself a compromise, and a weaker Senate bill could be worse than no bill at all.

They have left themselves wiggle room by writing “could be worse” rather than “would be worse,” but the clear lean is against sacrificing substance for legislative progress. You have to look hard to see it, but in legislative vernacular the New York Times editorial board is leaning toward having “an issue rather than a law.”

In a legislative body you never get everything you want. The strategic questions generally look like this:

- How much of our final goal can we get through the Congress and signed into law now? Three-fourths? Half? A quarter?

- If we get a signed law now that is [half] of our goal, does that make it easier or harder for us to get the rest of our goal in the future? You can argue, for instance, that getting a cap-and-trade mechanism in place is the hard part, and that once the mechanism is in place, it is relatively easier to pass new legislation in the future to tighten those caps. On the other hand, once a first bill is in place, the legislative momentum will be gone, and for at least several years it will be harder to generate new enthusiasm for a second bill that tightens the caps.

- Does our legislative hand get stronger or weaker over time? If you think political support for your position will strengthen over time, that maybe you should forego the bird now and wait for an improved future chance at two in the bush. If instead you think political support for your position will weaken over time, then you should grab whatever you can get now.

I offer here my positive analysis (how I think things are) of the legislative situation rather than my normative analysis (how I would like things to be). Unlike much of what I have posted on other topics, I can prove none of the following. Please consider this a well-informed set of guesses.

- I don’t think cap-and-trade advocates can get the Senate to pass any bill pricing carbon before the end of this Congress (December 2010). I just don’t see how they get to 60 votes, even if they were to substantially weaken the House-passed bill. They can get only a small portion of their goal now.

- If President Obama were to sign a “climate change bill” (as opposed to a bill pricing carbon) into law, momentum for a future carbon pricing bill would slow somewhat. So if a bill pricing carbon cannot pass the Senate, the President could instead almost certainly get a “clean energy” bill to his desk that increases mandated energy efficiency standards, maybe includes a “renewable electricity standard,” and spends a bunch of money on climate change R&D. But signing such a law would take some of the political goodies out of a future carbon cap bill, making it harder to pass. I think the President and his team have positioned themselves to be able to sign such a law and declare partial victory. The President almost never talks about “climate change” or “pricing carbon,” but instead about “clean energy technologies.”

- I am unclear about whether Senate support for a carbon pricing bill would be higher in 2011 and 2012 than it is now. There is no clear long-term trend. If I had to wager, I would offer 3:2 odds that there would be less Senate support for Waxman-Markey (or almost any specific carbon pricing bill) two to three years from now than there is today. Note that I am hypothesizing about support from Senators, rather than what public opinion polls might say. The two are related but not identical.

If my legislative analysis is correct, then cap-and-trade advocates are going to face a letdown. They will fail to get 60 votes in the Senate, and will then be forced to decide whether to enact a “climate change bill” without a carbon price. If they do, they further reduce their future chances of enacting carbon pricing legislation. Either way, I think (guess) that their chances decline over time.

In a future post I will explain my opposition to the House-passed bill. For now I challenge you to look on this as an exercise of legislative analysis and strategy rather than one of advocacy:

- Whatever your view on what should happen, do you agree with my analysis of the legislative situation? If not, with which specific assumptions do you disagree, and why?

- For those who support the House-passed bill: Suppose my analysis of the legislative environment is correct. Would you want a “climate change law” now (by 12/2010) that drops the carbon pricing mechanism, or would you rather wait and save those relatively easy provisions to package with a future legislative attempt at a carbon pricing law?

If this were an exercise for a class, I would dock points from anyone who responds by telling me why we should support or oppose the House-passed bill. That’s a question for another day and another post.

(photo credit: The old “cut the polar pear in half” trick! by ucumari)

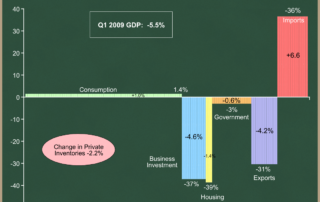

Understanding first quarter GDP

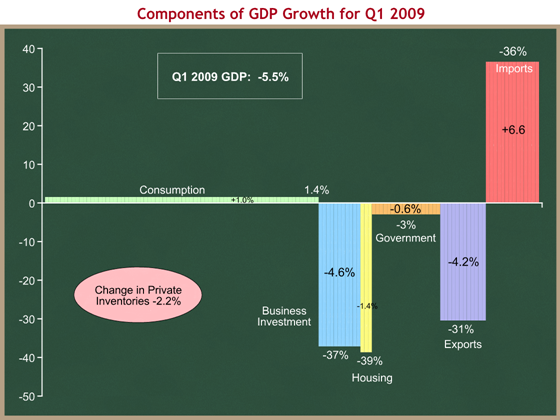

Last Wednesday the Commerce Department released their final data for first quarter (Q1) U.S. GDP. GDP shrank at a 5.5 percent annual rate in the first quarter of this year. (This takes inflation out of the calculations, so we’re measuring the growth of real GDP.) That doesn’t mean it shrank 5.5% that quarter. It means that it shrank at a rate that, if extended through a whole year, would cause GDP to shrink 5.5% over the course of that year. If the economy is performing well, it’s growing a little faster than 3% per year. We were more than eight percentage points below that in the first quarter of this year.

I find it useful to understand how the major components of GDP are performing. The graph below allows us to do that. I created this format while in the White House for my own use, and now I’d like to share it with you. Please bear with me – there’s a lot of information in one graph, and it may take some getting used to. Here’s the summary:

- The width of each component bar represents its share of GDP.

- The height represents the growth rate of that component. This growth rate is labeled in white immediately above or below that bar.

- The black number within the bar shows that component’s contribution to the overall growth rate of -5.5%

- Private inventories and Imports require special explanation.

Consumption is the widest bar. People buying stuff to consume accounts for, on average, about 70% of GDP. Right now it’s 72%. This explains why economists and market forecasters care so much about measures of consumption. If consumption grows modestly, the economy will grow. You can see from this graph that consumption grew at a 1.4% rate in Q1. Multiply 1.4% by 72% of the economy, and you get +1.0 percentage points of GDP, the number in black within the green bar. Consumers contributed to a positive 1.0% annual growth rate, while the rest of the picture subtracted 6.5 percentage points, resulting in a net -5.5%.

The bottom fell out of both business investment and housing in Q1, shrinking at rates of 37% and 39% respectively. Those are disastrous numbers. Since business investment accounts for about 11% of GDP, and housing only about 3%, you can see that the decline in business investments took 4.6 percentage points off the aggregate growth rate, while housing knocked off another 1.4 percentage points. While everyone focuses on housing, we shouldn’t lose sight of the much larger effect of plummeting business investment.

Most of the world economy is shrinking. People in other countries don’t want to buy our stuff, so our exports plummeted at a 31% rate. Similarly, we’re not buying stuff from other countries, so our imports declined 36%. Because of the way GDP arithmetic works, a decline in imports adds to GDP growth. This is the one big flaw in this graph format – I put the imports bar in positive territory because it adds to GDP growth, but imports actually shrank. I’d appreciate suggestions on how to make this work better visually. The net effect is that the decline in exports was more than offset by the decline in imports, so the effect of net exports (exports – imports) actually contributed 2.4 percentage points to GDP growth in Q1.

The bad news is that inventory investment was negative, subtracting 2.2 percentage points to the overall growth rate. The good news is that the change in private inventories contribution tends to be cyclical. As inventories get drawn down, there eventually is a need to rebuild those inventories. So while other drags (like housing) could continue for a while, I would expect that the pink oval will eventually move back into positive territory.

The overall picture is for Q1 was, unsurprisingly, bleak. Were it not for the consumer still continuing to spend, things would have been even worse.

The stimulus law will effect this eventually by raising that orange bar, government spending, into positive territory. The tax code changes and expanded unemployment insurance benefits have a small positive effect on the green consumption bar.

I wrote on June 3rd that I thought the Obama Administration made a huge mistake in the way they designed the stimulus, even given the President’s policy preferences. They’re pushing most of the money out through the government channel, represented by the orange bar above. The problem is that these dollars spend out incredibly slowly, and so the orange bar won’t be boosted significantly until Q4 of this year (at the earliest).

They should have pumped all the money out to consumers. Consumers would have saved more than half of those funds, but given that it was a $787 B package, if consumers spent only one-third that amount, you would have seen an immediate and significant upward bump in the green bar, beginning at the end of Q2 (now), and into Q3 and Q4. Stimulating consumption results in only a portion of the dollars going to higher GDP growth, but it happens much more quickly than trying to force money out the door through government bureaucracies. By allowing their Democratic Congressional allies to funnel stimulus dollars through government programs, they unnecessarily delayed the bulk of the positive economic benefit until next year.

Let’s hope the Q2 numbers are less bad. We will see the first data in the last week of July. Whatever the results, they will be largely independent of the stimulus, which is having only a small positive effect even now. The scary scenario is the one where the labor market continues to decline, and that causes consumption to go negative before the other sectors have time to recover.

How much bailout money will taxpayers get back?

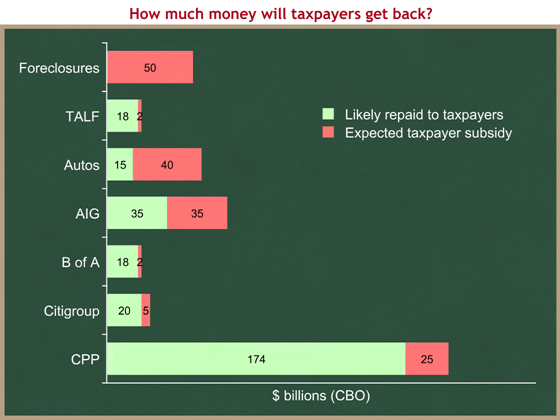

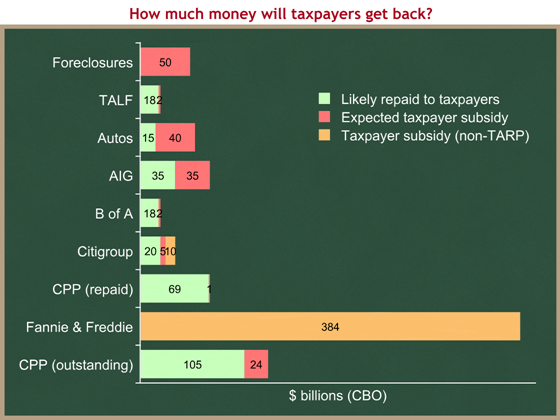

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has released their assessment of the Office of Management and Budget’s semiannual TARP report. That assessment estimates how much cash has gone out the door for each part of TARP, and how much CBO expects will ultimately be returned to the Treasury. I have converted CBO’s table (Table 1 on page 2) to a set of graphs. Looking at the Capital Purchase Program (CPP) in the bottom bar, $199 B has gone out the door in outlays, and CBO expects $174 B of that will be paid back. CBO calculates a subsidy rate for each program, which for CPP is 25 / (174 + 25) = 13%. Taxpayers should expect to recoup 87% of the funds that were invested on their behalf in the Capital Purchase Program and lose the other 13%.

You can see from the graph that most of the funds went to capital purchase: CPP + specific firm deals (AIG, Bank of America, and Citigroup). CBO thinks we taxpayers will get most of our money back from Bank of America and Citigroup. We’ll get about half back from AIG, and a little more than a quarter back from the autos and auto finance companies. The Administration’s foreclosure mitigation program is a spending program, not an investment, and thus we expect to get none of those funds back. Footnote (d) on CBO’s table contains a surprise: “The Treasury has not yet disbursed any of the $15 billion allocated as of June 17, 2009, for foreclosure mitigation.” We heard a lot about the President’s efforts on foreclosure mitigation, and yet no cash has flowed.

To answer the question, “How much bailout money will taxpayers get back?” CBO estimates that:

- $439 B of the original $700 B has been spent;

- $280 B of that will be repaid; and

- $159 B will not be repaid and will be a cost to the taxpayer.

CBO provides further detail on the Capital Purchase program by subdividing it into two parts: CPP for the 32 banks that have already paid back the Treasury, and CPP for all the other banks. Here’s the same graph, but with CPP split into those two parts. You can see that the net cost to the taxpayers from the 32 banks that have already paid back Treasury was (only) $1 B. CBO is guessing a much higher loss on the remaining outstanding CPP investments.

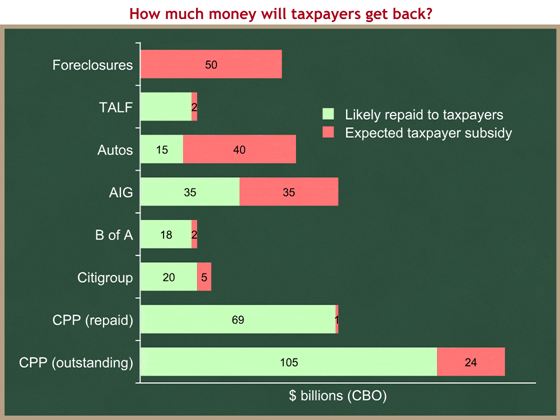

We do not have similar estimates for all of the Fed actions, but we do for the FDIC’s actions, and for the bailout of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The picture changes dramatically when we add these non-TARP financial rescue funds. Courtesy of Sen. Judd Gregg’s excellent Senate Budget Committee Republican staff, I’m going to add in orange the estimated taxpayer costs of FDIC’s component of the Citigroup rescue, and CBO’s estimate of the taxpayer cost of bailing out Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

CBO estimates that the cost to the taxpayers of the failure of the GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, will be $384 B. That is 2.4 times larger than all the other TARP and non-TARP costs (shown here, and excluding the Fed) combined. Here’s the Budget Committee Republican staff’s Budget Bulletin:

CBO estimated that the federal government immediately absorbed a loss of $248 billion for the book of business the GSEs had in September 2008. To maintain an active mortgage market, the federal government is continuing to operate the GSEs, whose new commitments entered into after September 2008 would lose an estimated $136 billion over the 2009-2019 period according to CBO.

Thus when we rank the expected cost to the taxpayers of the different TARP and non-TARP programs, we get:

- Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac ($384 B)

- Foreclosure mitigation ($50 B)

- Autos & auto finance ($40 B)

- AIG ($35 B)

- Outstanding equity investments in banks through the Capital Purchase Program ($24 B)

- Citigroup ($15 B)

- Bank of America ($2 B)

- The direct Treasury cost of the Fed’s liquidity facility ($2 B)

- Repaid equity investments in banks through the Capital Purchase Program ($1 B)

That $384 B number is huge.

And updating to include TARP + FDIC + GSEs (but not the Fed facilities), it appears CBO estimates the net cost to the taxpayer of all these non-Fed facilities will be about $553 B.

Thanks to Jim Hearn of Sen. Gregg’s Budget Committee staff for his incredible table and assistance.

Sources:

- CBO’s The Troubled Asset Relief Program: Report on Transactions through June 17, 2009

- Senate Budget Committee Republican Staff’s Budget Bulletin (June 25, 2009)

If you’re really into budget policy, you should keep your eye on the Budget Bulletin. You can subscribe by emailing their webmaster, whom you can find here.

From borrow-and-spend, to tax-and-spend

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer and Rep. George Miller, Chairman of the House Democratic Policy Committee, write in today’s Wall Street Journal that “Congress Must Pay for What It Spends,” subtitled “Democrats won’t be the party of deficits.” They argue in favor of their pay-as-you-go, aka “paygo” rule. I have a different perspective and offer it here in response.

The paygo rule is a self-imposed Congressional rule designed to make it harder to enact legislation that violates certain budgetary conditions. There are two variants, known as two-sided paygo (favored by most Democrats, including Leader Hoyer and Chairman Miller), and one-sided paygo (favored by most Republicans, including me).

- two-sided paygo makes it harder to enact legislation that increases the federal budget deficit, whether as a result of increased spending or lower taxes;

- one-sided paygo makes it harder to enact legislation that increases the federal budget deficit as a result of increased spending (only). One-sided paygo does not raise procedural barriers to cutting taxes.

Both versions have common features:

- They are rule changes specific to each body (the House and Senate) that can we waived with a simple majority in the House, and with 60 votes in the Senate.

- They do not by themselves reduce the deficit.

- They do not prevent government from getting bigger, if spending increases are accompanied by tax increases of the same size.

- They do not prevent the deficit from going up due to external factors like a recession or an increase in inflation. They only inhibit new deficit-increasing laws.

There used to be a stronger version of statutory paygo that included the Executive Branch. This version has fallen out of favor.

Since these points are somewhat disjoint, and since the blogosphere seems to love a numbered list, here are my thoughts in response to Leader Hoyer and Chairman Miller.

- After enacting a stimulus law that increased future deficits by $787 billion directly, Leader Hoyer and Chairman Miller argue for Congress to act responsibly. They begin by blaming the Bush Administration for the current budget deficit, but ignore their actions of the past five months that have made future deficits significantly larger. Now that the horses are all out of the barn, they argue we should lock the door tight. (A friend points out that most of the stimulus bill was discretionary spending which would not have been covered by any paygo rule. I guess the pigs, too, have left the barn.)

- In effect, they are arguing that Congress should shift from the borrow-and-spend regime of the past five months to a new tax-and-spend regime. While paygo makes it harder to increase the deficit, it does not limit expansions in government as long as they are accompanied by tax increases. Spending $1.6 trillion on health care is OK under two-sided paygo, if it’s offset by the same amount of tax increases. Similarly, a massive expansion of government through the impending cap-and-trade bill does not violate their two-sided paygo rule since it raises power costs by imposing new taxes on power producers.

In contrast, I care about budget deficits and about the size of government. On the whole government allocates resources less efficiently than the private sector, so when government expands at the expense of the private sector, we make the total American pie smaller. That’s a key reason why I’m a small government guy, and why I tend to oppose most expansions of government spending, even when their deficit impact is offset by higher taxes. Just because it’s “paid for” doesn’t mean the government should do it. - While their op-ed is written as Democrat v. Republican, an intraparty subtext is evident. Since the House can waive any paygo rule with 218 votes, the rule they advocate places no practical limit on their majority party if that party is united. Paygo rules matter much more in the Senate. Instead, this rule provides rhetorical leverage when the House leaders and committee chairmen are meeting in Speaker Pelosi’s office, debating whether a big new spending bill needs to be offset. Paygo is a useful tool for Mr. Hoyer and Mr. Miller behind those closed doors when they want to argue in favor of a tax-and-spend approach, in contrast to their borrow-and-spend Democratic colleagues (who tend to be farther Left).

- More broadly, fiscal policy is far more complex than the simple partisan split suggested by Messrs Hoyer and Miller. The makeup of both parties has changed over the past 15 years that I have been in Washington. There are no more tax-cutting Democrats in Congress: Sen. Breaux and Sen. Torricelli used to cause their party no end of heartburn by working with Republicans to cut taxes. There is also no viable Democratic Congressional faction to actually reduce the debt. Budget Chairmen Spratt and Conrad argue the case, and are routinely overruled by their colleagues who want to use all tax increases to offset new spending priorities. On the Republican side, more Republicans have been captured by spending constituencies, and for almost any spending bill there is a natural Republican constituency who will work with Democrats to increase spending without offsetting spending reductions (e.g., agriculture, highways, health research, border security).

- Two-sided paygo focuses on deficits. One-sided paygo focuses on deficits caused by increased spending. I believe our most serious deficit challenge is the long-term problem, driven by the growth rate of entitlement spending. I therefore want to make it harder for Congress to exacerbate this specific problem, and thus I favor one-sided paygo.

- If you think of tax cuts as “the government giving up revenue,” this naturally leads you to two-sided paygo. If instead you think of tax cuts as “preventing the government from taking money from the people who earned it,” this leads you to one-sided paygo. I don’t think of tax cuts as something that the government must “pay for.” I don’t want to make it harder for the government to take less money from the people who earn it. This is a philosophical difference: advocates of two-sided paygo often use “we” to refer to the government and its deficits. Advocates of one-sided paygo generally use “we” to refer to taxpayers.

- I believe that Leader Hoyer is one of only a handful of powerful Democrats who would like to reform our entitlement programs to address our Nation’s long-term spending challenge. I believe he would be a leader on bipartisan Social Security reform, if Speaker Pelosi did not prevent him from doing so. My private sources confirm recent press reports that the White House quietly reached out to Democratic Congressional leaders to explore the possibility of working on Social Security reform, only to be shut down by Speaker Pelosi. Similarly, in 2005 when we in the Bush White House quietly approached certain Senate Democrats to see if they would enter into negotiations with us over Social Security reform, we were told repeatedly that Leader Reid forbade them from negotiating with us.

- Leader Hoyer will soon confront a difficult situation in which his paygo rules will not help. House Democrats will produce a health care bill which will contain the largest expansion of entitlement spending since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. I assume they will comply with the paygo rules by slowing the growth of Medicare and Medicaid spending, and/or increasing taxes, so that the bill does not increase the deficit over the next 10 years. But because health spending grows faster than the economy, and taxes grow at the same rate as the economy, it is highly likely that such a bill will make our Nation’s long-term deficit situation even more bleak than it is today. It will also substitute a new politically popular entitlement for the least popular Medicare and Medicaid spending, making it more difficult to bring the spending growth of those programs down to address future deficits. Leader Hoyer will then be called upon by the Speaker and the President not only to vote for such a bill, but to help round up the votes to pass it, and to place his credibility on fiscal policy at risk by arguing that this massive new deficit-exploding entitlement expansion is fiscally responsible because it complies with his short-term paygo rules.

A wise man once said to me in a paygo discussion, “The problem isn’t the process. The problem is the problem.” Elected officials have spent countless hours debating one-sided vs. two-sided paygo, in large part because it’s an easy and theoretical fight. Nobody’s ox is directly gored when the paygo rule is being voted upon. Actual legislating to slow the growth of Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid spending involves real pain to real people who complain loudly. Unfortunately, that’s what must happen to prevent eventual budgetary collapse. Trumpeting process changes is a poor substitute for making the necessary and difficult legislative changes to slow the growth of the entitlement programs that constitute America’s long-term deficit problem.

(photo credit: Piggy savings bank by alancleaver_2000)

The President’s press conference: health

Let’s look at what the President said about health care reform in his press conference yesterday:

Like energy, this is legislation that must and will be paid for. It will not add to our deficits over the next decade. We will find the money through savings and efficiencies within the health care system — some of which we’ve already announced.

The first sentence is good. By using “must” and “will be,” he is telling Congress that “not add

I believe the President is referring to this week’s prescription drug announcement when he says, “We will find the money through savings and efficiencies within the health care system … some of which we’ve already announced.” This is mixing apples and kumquats. Budget rules require you to offset government spending increases with tax increases or cuts in government spending. The pharmaceutical industry announced they would reduce the amounts they would charge Medicare beneficiaries by $80 B over the next ten years. The industry proposal will save money for seniors, not for the government. So the health care savings and efficiencies “which we’ve already announced” have nothing to do with [federal budget] “deficits over the next decade.”

We will also ensure that the reform we pass brings down the crushing cost of health care. We simply can’t have a system where we throw good money after bad habits. We need to control the skyrocketing costs that are driving families, businesses, and our government into greater and greater debt. …

… Unless we act, premiums will climb higher, benefits will erode further, and the rolls of the uninsured will swell to include millions more Americans. Unless we act, one out of every five dollars that we earn will be spent on health care within a decade. And the amount our government spends on Medicare and Medicaid will eventually grow larger than what our government spends on everything else today.

At some point this excellent language, which the President uses frequently, must confront the reality that nothing Congress is contemplating would actually do this. I can find only one provision in the Kennedy-Dodd draft that could claim to reduce private health care spending – a provision which would give the Secretary of HHS authority to mandate that firms effectively lower the premiums they charge by rebating a portion of those premiums to consumers. Even this provision does not address the primary driver of health cost growth, which is the interaction between low-deductible insurance and new medical care technology.

Aside from that (highly objectionable) provision, I can find nothing that would provide information and incentives to consumers, medical professionals, health plans, employers, or governments to slow the growth of long-term private health care spending.

I believe the President means this when he says it. His staff and the Congress are failing to deliver on this goal. At some point soon, it will be too late to introduce these needed but politically painful changes into legislation.

There’s no doubt that we must preserve what’s best about our health care system, and that means allowing Americans who like their doctors and their health care plans to keep them.

… Well, no, no, I mean — when I say if you have your plan and you like it and your doctor has a plan, or you have a doctor and you like your doctor that you don’t have to change plans, what I’m saying is the government is not going to make you change plans under health reform.

The legislation being developed does not fulfill this goal. Then again, no legislation could. This is a Presidential overpromise (and a serious tactical error) that the Congress will be unable to fulfill. CBO says the Kennedy-Dodd bill would cause 10 million people to lose their current employer-based insurance because their employer stops offering it, even if those people like their health plan and want to keep it.

I think in this debate there’s been some notion that if we just stand pat we’re okay. And that’s just not true. You know, there are polls out that show that 70 or 80 percent of Americans are satisfied with the health insurance that they currently have. The only problem is that premiums have been doubling every nine years, going up three times faster than wages. The U.S. government is not going to be able to afford Medicare and Medicaid on its current trajectory. Businesses are having to make very tough decisions about whether we drop coverage or we further restrict coverage.

So the notion that somehow we can just keep on doing what we’re doing and that’s okay, that’s just not true. We have a longstanding critical problem in our health care system that is pulling down our economy, it’s burdening families, it’s burdening businesses, and it is the primary driver of our federal deficits. All right?

This is a straw man. As an example, I strongly oppose both the Kennedy-Dodd draft and the House draft of health care legislation, but I don’t believe that if we just stand pat “we’re okay.” There will be health insurance and health provider interest groups arguing we need to maintain elements of the status quo because they benefit financially from those elements. The President’s comments, however, ignore that there are others who agree with him on the goal of slowing health care cost growth, but have a different way to go about it.

I would repeal the current-law exclusion for employer provided health insurance and replace it with a standard deduction not tied to employment. I would make changes in health insurance law to allow you to take your health insurance with you when you left your job (“portability”), and to shop outside your state to buy health insurance so that insurers were forced to compete for your business. I would change medical malpractice laws. All of these changes would actually slow private health cost growth by creating incentives for individuals to shop for high-value health care. I, for one, am not for the status quo, even though I oppose the bills being developed in the Congress. (I will explain my proposal in more detail at a later date.)

So if we start from the premise that the status quo is unacceptable, then that means we’re going to have to bring about some serious changes. What I’ve said is, our top priority has to be to control costs. And that means not just tinkering around the edges. It doesn’t mean just lopping off reimbursements for doctors in any given year because we’re trying to fix our budget. It means that we look at the kinds of incentives that exist, what our delivery system is like, why it is that some communities are spending 30 percent less than other communities but getting better health care outcomes, and figuring out how can we make sure that everybody is benefiting from lower costs and better quality by improving practices. It means health IT. It means prevention.

It means changing incentives. More precisely, it means eliminating policy-induced incentives that encourage people to ignore the costs of the health insurance they buy and the medical care they use. It means repealing the tax treatment of employer-provided health insurance.

Conventional wisdom is that the Obama White House is afraid of political blowback if they endorse this reform, especially from organized labor. They are leaving the door open to it if Congress chooses to include it.

I hope the President’s negotiators are privately offering specific proposals to change incentives in private sector health insurance markets and health care delivery, because they have offered no such proposals publicly. The President and his team have offered specific proposals to increase the amount of information available, but not to change the incentives. As CBO and I have explained, you need to do both.

Number two, while we are in the process of dealing with the cost issue, I think it’s also wise policy and the right thing to do to start providing coverage for people who don’t have health insurance or are underinsured, are paying a lot of money for high deductibles.

But the Kennedy-Dodd draft would increase federal health entitlement spending by 11%. The savings being proposed are far exceeded by the new entitlement expansion.

Also, when you expand government-financed health insurance coverage, private sector health spending goes up, not down. So while a new government insurance program will help those people who were previously uninsured, it will make solving the long-term health cost growth problem more difficult.

Now, the public plan I think is a important tool to discipline insurance companies. What we’ve said is, under our proposal, let’s have a system the same way that federal employees do, same way that members of Congress do, where — we call it an “exchange,” or you can call it a “marketplace” — where essentially you’ve got a whole bunch of different plans. If you like your plan and you like your doctor, you won’t have to do a thing. You keep your plan. You keep your doctor. If your employer is providing you good health insurance, terrific, we’re not going to mess with it.

This is the most frequent argument for a public health option – that it will “discipline insurance companies.” It’s a useful political argument because insurers are unpopular.

In most other sectors, however, we rely on market competition to discipline sellers. If you don’t like the company that sells you X, you instead buy from their competitor. I have not seen any evidence, nor heard any arguments from the Administration, to demonstrate that market competition among insurance companies is ineffective. Are there antitrust issues or market barriers that necessitate government intervention? Do the President’s advisors believe that insurers do not operate in a competitive market? For this argument to have validity they need to make this case. I am skeptical but would like to hear the argument.

Q: Won’t [a government option for insurance] drive private insurers out of business?

THE PRESIDENT: Why would it drive private insurers out of business? If private insurers say that the marketplace provides the best quality health care, if they tell us that they’re offering a good deal, then why is it that the government … which they say can’t run anything … suddenly is going to drive them out of business?” That’s not logical.

I am reminded of the old George Carlin joke: “Think for a moment about flamethrowers. The Army has all the flamethrowers. I’d say we’re ****ed if we have go up against the Army, wouldn’t you?”

The government option for insurance would drive private insurers out of business because the government has tools available to it that the private sector does not. Imagine if a private firm could set the rules under which it competes for business with other private firms. The playing field will not be level when one option has the power and force of the government behind it. The Army has all the flamethrowers.

It’s easiest to make this case by example:

- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had a government imprimatur and specific policy advantages granted by the government that allowed them to dominate the mortgage securitization markets.

- The federal government set a statutory “fence” to protect the Tennessee Valley Authority (a government-run power company) from competing for customers with privately-owned utilities. They are immune from state rate regulation and have a different tax system.

- Ford Motor Company is now at a significant competitive disadvantage relative to the bailed out General Motors and Chrysler.

- Private property and casualty insurers are not selling terrorism insurance above a certain amount. They were crowded out by the government program.

- Direct student loans from the government are crowding out loans offered by private banks.

Q: Is [the inclusion of a government option for insurance] non-negotiable?

THE PRESIDENT: In answer to David’s question, which you co-opted, we are still early in this process, so we have not drawn lines in the sand other than that reform has to control costs and that it has to provide relief to people who don’t have health insurance or are underinsured. Those are the broad parameters that we’ve discussed.

There are a whole host of other issues where ultimately I may have a strong opinion, and I will express those to members of Congress as this is shaping up. It’s too early to say that. Right now I will say that our position is that a public plan makes sense.

Translation: Yes, it’s negotiable.

Now, by the way, I should point out that part of the reform that we’ve suggested is that if you want to be a private insurer as part of the exchange, as part of this marketplace, this menu of options that people can choose from, we’re going to have some different rules for all insurance companies — one of them being that you can’t preclude people from getting health insurance because of a pre-existing condition, you can’t cherry pick and just take the healthiest people.

So there are going to be some ground rules that are going to apply to all insurance companies, because I think the American people understand that, too often, insurance companies have been spending more time thinking about how to take premiums and then avoid providing people coverage than they have been thinking about how can we make sure that insurance is there, health care is there when families need it.

This is important, and it requires a full post in response. There are two points here:

- The President wants to change the rules for private health insurance, whether or not there’s a government option. I believe these rule changes will increase premium costs for most people.

- Even if the government option drops out of legislation, health insurance will largely become a function of government.

I will endeavor to keep you briefed as the health care debate continues. I expect a lot more activity over the next six weeks.

(photo credit: whitehouse.gov)