The President’s press conference: climate change

In his press conference yesterday, the President’s opening statement covered Iran, climate change, and health care. Here he is on climate change:

This energy bill will create a set of incentives that will spur the development of new sources of energy, including wind, solar, and geothermal power. It will also spur new energy savings, like efficient windows and other materials that reduce heating costs in the winter and cooling costs in the summer.

These incentives will finally make clean energy the profitable kind of energy. And that will lead to the development of new technologies that lead to new industries that could create millions of new jobs in America — jobs that can’t be shipped overseas.

He is still not referring to it as a “climate change bill,” nor does he ever say “cap-and-trade.” He refers once to “the carbon pollution that threatens our planet,” but continues to rhetorically frame this cap-and-trade legislation as a clean energy technology bill. He has been doing this consistently since his first press conference, and it reaffirms for me that his political and communications advisors think that addressing climate change is less popular than promoting clean energy technology.

Also, his last sentence is misleading. Raising the price of energy would lower U.S. GDP. We would produce less carbon and would have lower incomes. While the President did not say that this bill would help the economy by creating a net increase in jobs, he creates that impression by saying “that lead to new industries that could create millions of new jobs in America.” It is misleading to suggest that cap-and-trade legislation, such as that being considered this week by the House of Representatives, will not harm the economy. You can argue that the environmental benefits are worth the economic cost, but not that this will increase U.S. economic growth.

I don’t understand why he thinks that jobs that could be created in clean energy technologies would necessarily be created in America, or why they could not be shipped overseas. I can see why the windmill maintenance guy and the solar cell installation firm would have to be based in America (like the classic economics course example of not being able to outsource haircuts).But solar cells and windmill parts, as well as batteries, new building materials, and nuclear power plant components can all be designed, developed, and manufactured anywhere in the world. The U.S. clearly has an R&D head start on the rest of the world, but I don’t see why the President thinks these jobs “can’t be shipped overseas.”

This Presidential statement is a rhetorical flourish, but I’d be interested to see CEA Chair Dr. Christina Romer try to defend it in front of an audience of her academic colleagues. I think it’s indefensible:

The nation that leads in the creation of a clean energy economy will be the nation that leads the 21st century’s global economy.

This statement is true but incomplete:

At a time of great fiscal challenges, this legislation is paid for by the polluters who currently emit the dangerous carbon emissions that contaminate the water we drink and pollute the air that we breathe.

Thanks to a grad school professor, I have forever imprinted the question-and-answered, “Who pays taxes? PEOPLE pay taxes.” The President is correct that the costs of a cap-and-trade system would be directly imposed on those who produce power and fuel from carbon-based energy sources. But power companies, like all firms, are aggregations of economic interests. They would pass these costs through to their owners, employees, and customers. So one could even more accurately say that “This legislation is paid for by anyone who uses electricity from a coal-fired or nautral gas-fired power plant, who drives, or who buys anything that has power or fuel as an input.” It is also paid for by the hard-working employees of those companies, and by those who own stock in those companies.

Finally, I wish he would mention nuclear power when he talks about new sources of low-carbon energy. Not doing so suggests a political calculation, because nuclear power is the one non-carbon power source that many on the far left oppose.

(photo credit: whitehouse.gov)

Demographics is a bigger problem than health care costs

The President and Budget Director Peter Orszag frequently say we need to “bend the health care cost curve downward” to address our long-term fiscal problems. This is correct but incomplete.

Here is Director Orszag, writing in last week’s Financial Times: (emphasis added)

As the healthcare debate picks up in the US, there has been much discussion about how to pay for it. Coinciding with this debate are vocal concerns about the country’s underlying fiscal position … which some have suggested as a reason to delay healthcare reform.

What this argument ignores is that healthcare is central to the long-term fiscal and economic prospects of the US. If costs per enrollee in Medicare and Medicaid grow at the same rate over the next four decades as they have over the past four, those two programmes will increase from 5 per cent of gross domestic product today to 20 per cent by 2050.

Healthcare cost growth dwarfs any of the other long-term fiscal challenges the US faces. Nothing else we do on the fiscal front will matter much if we fail to address rapidly rising healthcare costs.

Director Orszag is correct that rising per-capita health spending is a key driver of our long-term fiscal problems. But he overstates his case by ignoring the other driver of federal spending growth, demographics. We need to address both. We need health care reform that will slow the growth of per capita health spending. And we need to change the promises made under Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid to adjust for a rapidly aging U.S. population.

Let’s look at a graph from the President’s Budget (page 191 of the Analytical Perspectives volume):

This chart shows the combined effects on the big three entitlement programs (Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security) of two factors: demographics, and age-adjusted per capita health cost growth. The effect of demographics is larger than the effect of “excess growth in health care costs” up until some time in the 2040s. This is why Director Orszag chooses 2050 to make his case.

Director Orszag’s own graph shows that the aging of the population is a bigger driver of spending increases in the federal budget for the next 30-40 years.

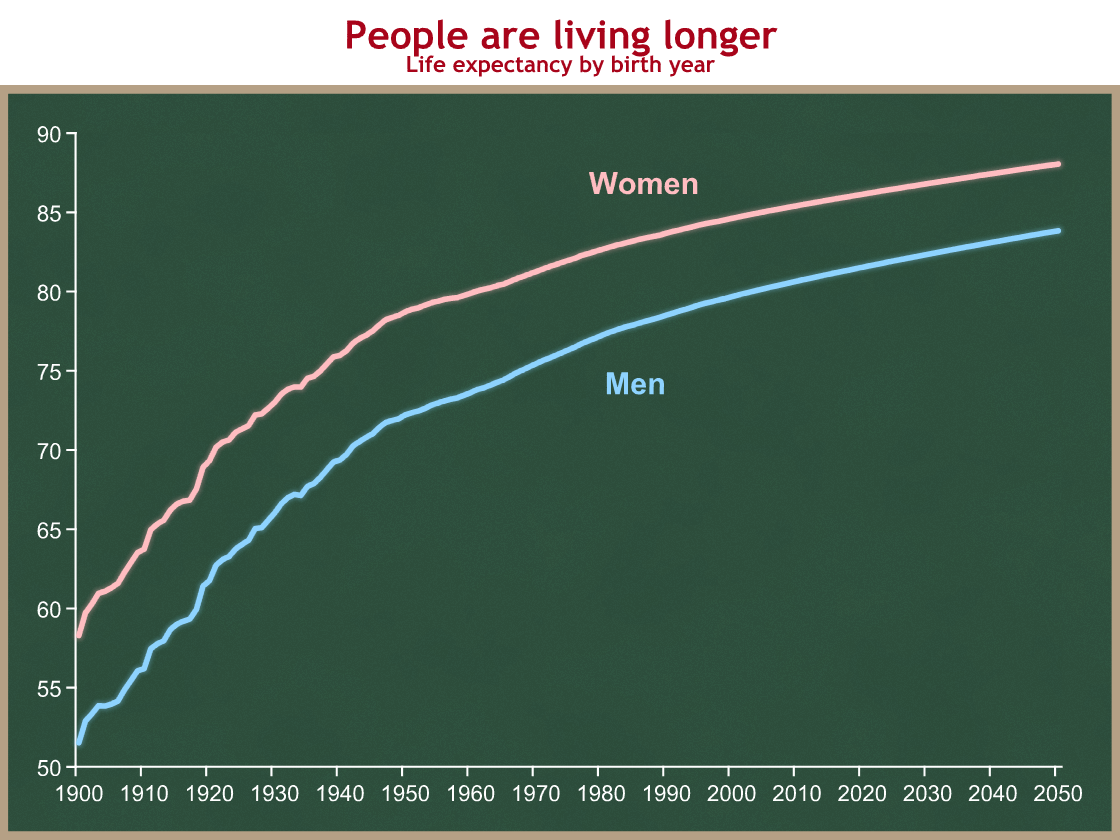

There are two forces driving the aging of the U.S. population. People are living longer. This is a good thing.

This means people are collecting benefits for more years. That’s good for people and expensive for the government.

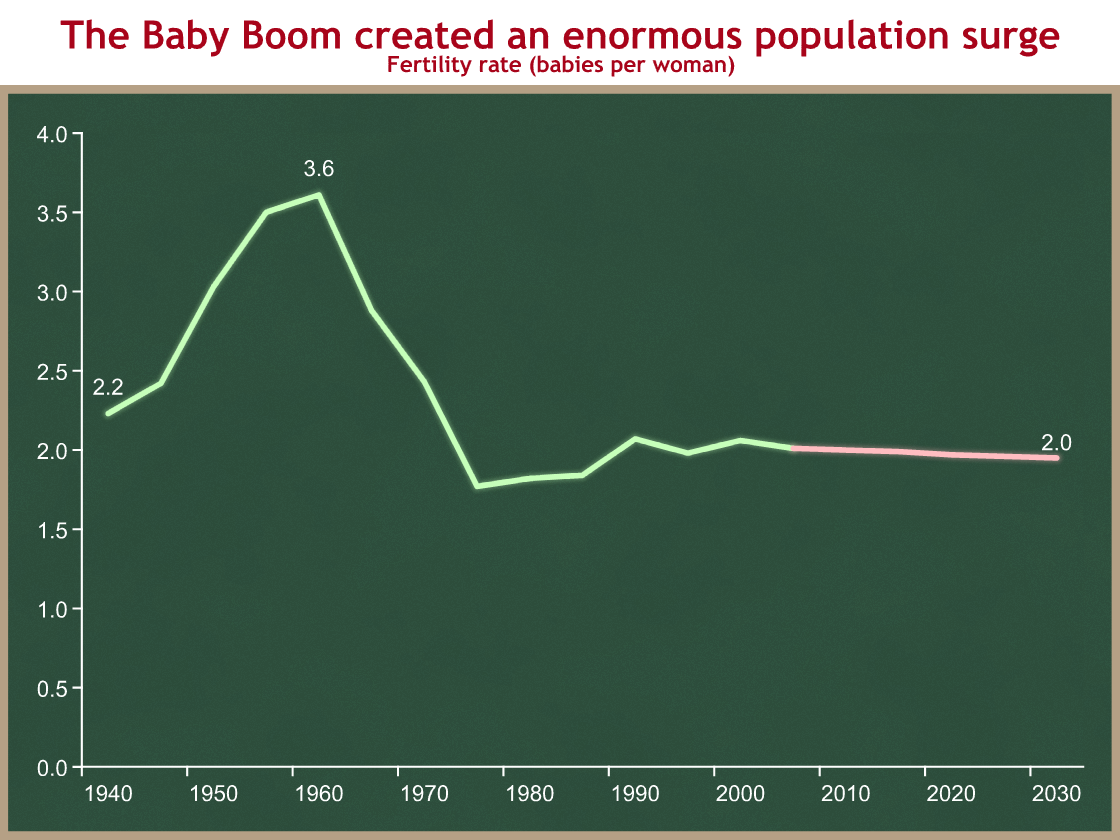

Longer life expectancies are a permanent and positive feature of the U.S. demographic landscape. There is a second, transitory cause of the aging of the U.S. population: the Baby Boom. Fertility rates surged after World War II. Before and during the war, each woman had on average about 2.2 – 2.4 babies. That surged to 3.6 babies per woman in 1960, and is now down to 2.0, where it is predicted to stay.

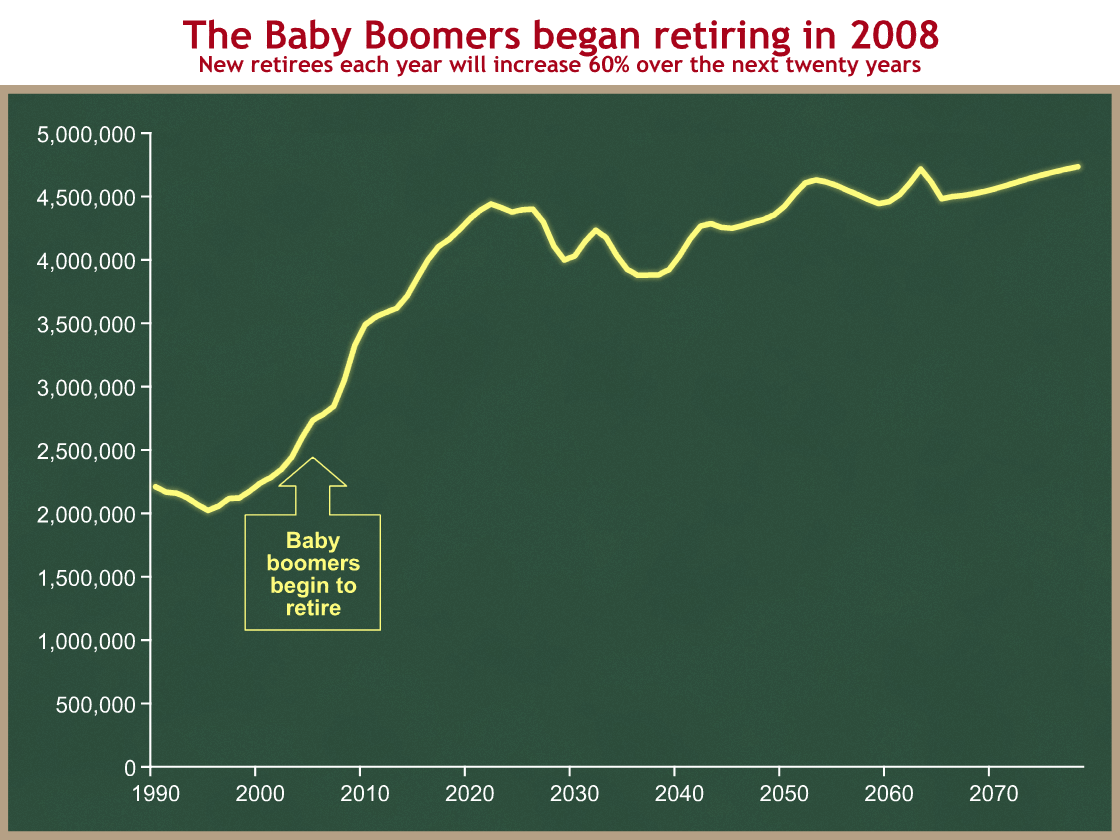

The Baby Boom began in 1946. You can start collecting early retirement benefits under Social Security at age 62. This means the first cohort of Baby Boomers started collecting their checks in 2008. You can see how the number of new retirees each year is going to spike over the next ten years.

I think of longer lifespans as a permanently rising tide, and the Baby Boom as a huge wave that supplements that tide. Together, the two of them mean that America is rapidly aging. This is affecting federal and state budgets beginning now. Since Social Security and Medicare are pay-as-you-go systems, in which current workers pay for the benefits of current retirees, this means a larger tax burden is placed on each younger worker. (No, the government does not save your payroll taxes. It has spent and is spending them on other stuff.)

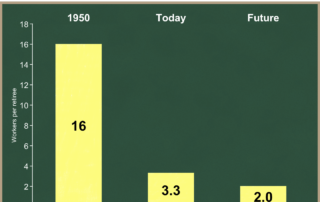

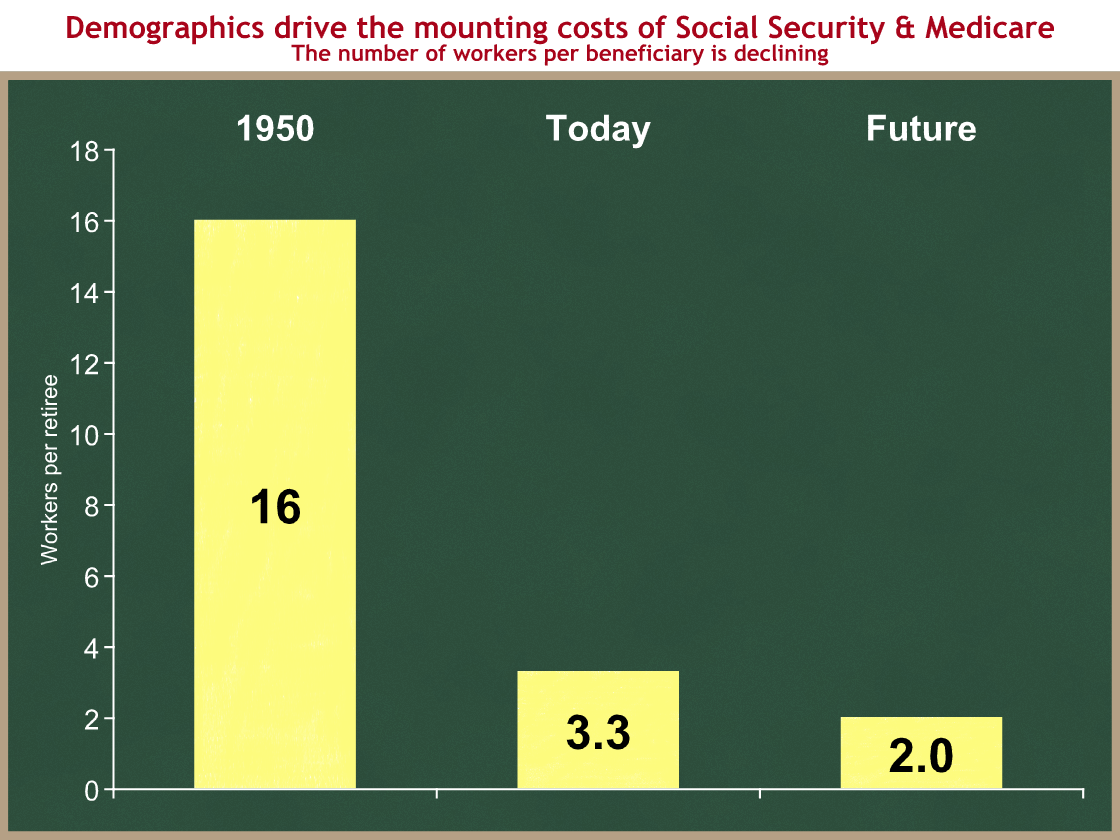

In 1950, there were 16 workers paying payroll taxes for each retiree collecting Social Security benefits. Today, there are 3.3 workers supporting the Social Security and Medicare benefits of each retiree. In the future there will be only 2 workers paying taxes to support the benefits of each retiree.

The rapid growth of per capita health spending in the U.S. is a critical policy problem that needs to be addressed. It is not, however, the primary driver of our federal budget problems over the next 30-40 years. The aging of the population is. Policy changes need to address both pressures to prevent an eventual fiscal meltdown. We must not ignore demographics.

Director Orszag’s 10th year test and the health spending gap

The President and his Budget Director Peter Orszag argue they are being fiscally responsible when they support a massive new health entitlement. They are proposing savings in Medicare and Medicaid, and they are proposing ephemeral long-term policy changes that they argue will save money. The savings are insufficient to offset the new spending, and CBO says their long-term changes are insufficient to save money in the federal budget.

In last Monday’s Financial Times, President Obama’s Budget Director Peter Orszag wrote:

Healthcare cost growth dwarfs any of the other long-term fiscal challenges the US faces. Nothing else we do on the fiscal front will matter much if we fail to address rapidly rising healthcare costs.

Although his focus is too much on the far future (e.g., 2050, rather than 2020 or 2030), Director Orszag is correct that, if we don’t slow the growth of federal health spending, the U.S. budget and economy will in time collapse.

Director Orszag therefore deserves credit for making Congress’ job much harder last Wednesday, when he established a new Administration test for health care legislation by opening his blog post like this: (emphasis added)

As I have written before, the Administration is committed to the principle that health care reform must be deficit neutral over the next decade (as well as being deficit neutral in the 10th year alone).

Despite his “As I have written before,” I think the “10th year test” is new for the Administration. It jumped out at me, and I have been unable to find any previous references to it by Director Orszag or anyone else. Maybe they have been communicating it privately to their allies in Congress.

I commend Director Orszag for setting forth this new test, which I believe he intends as a proxy for addressing the long-term health spending trend. It’s an insufficient proxy, but it’s better than nothing. If your legislation does not increase the deficit in the last year that you measure budgetary effects, then you can argue that your legislation isn’t making things worse in the long run.

This is an insufficient proxy if Congress uses certain tax increases to close the gap, because of the difference in long-term growth rates between health spending and revenues. I’ll cover that another time. Today I want to examine the size of the gap between Director Orszag’s test and legislation being developed by Congressional Democrats. CBO and the Joint Tax Committee estimate the effects of legislation over a 10-year budget window. The “tenth year” for our purposes is 2019.

As a preview, here’s my conclusion:

Combining Kennedy-Dodd with all of the President’s proposed Medicare and Medicaid savings would make America’s long-term entitlement spending problem much worse than under current law.

This conclusion may be obvious if you are closely following this debate. But the President and his Budget Director continue to assert that they are being fiscally responsible by supporting this new entitlement. Those repeated assertions demand a rigorous analytical response. I am going to walk through this step by step, to try to prove they are wrong.

Let’s look at some pictures.

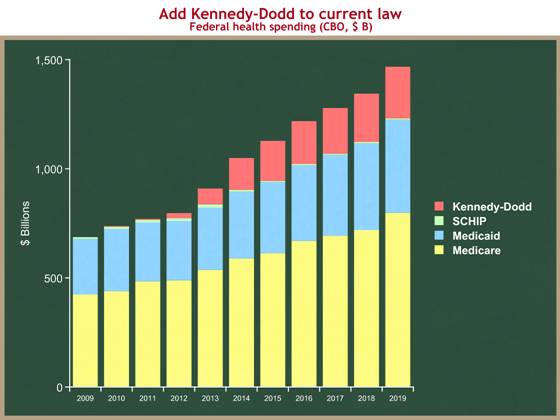

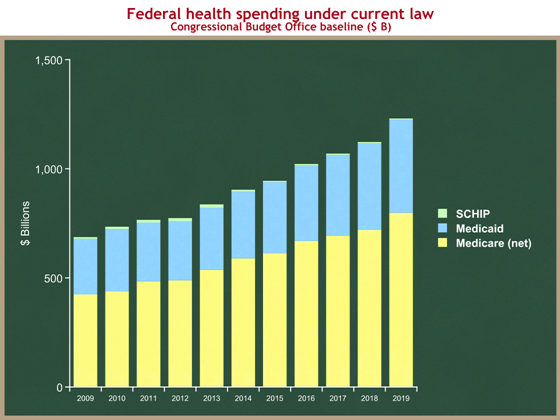

Here is federal health entitlement spending under current law. The graph below shows huge programs growing at an unsustainable rate. Under current law, spending on these three programs would grow from $676 B this year, to $1,228 B in 2019. (And I think CBO is being optimistic.)

As always, you can click on any graph to see a larger version.

Here’s technical stuff for the budget wonks:

Here’s technical stuff for the budget wonks:

- Source: CBO’s Baseline Projections of Mandatory Outlays (Table 1-8)

- Medicare spending is net of premiums

- These are federal expenditures, so Medicaid is the federal share.

- CBO uses baseline SCHIP spending, which drops from $14 B in 2013 to $6 B by 2015. This is unrealistic, but it helps make the Democrats’ job easier, so I’ll leave it this way for now.

Let’s add the proposed new health spending in the Kennedy-Dodd bill, as scored by CBO. You can see it would significantly increase federal health spending.

- Source: page 10 of CBO’s June 15, 2009 letter to Chairman Kennedy

- I’m showing net increased health spending from Kennedy-Dodd. On the next graph I will include the effects of higher taxes under Kennedy-Dodd.

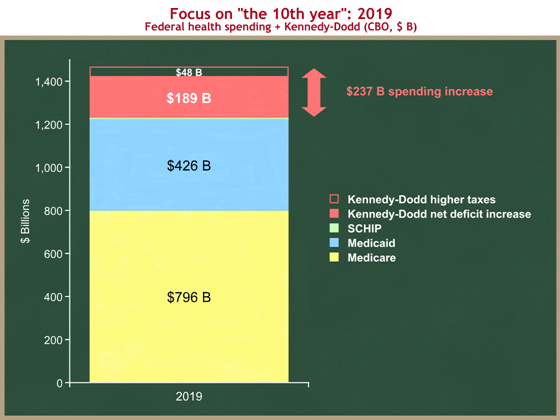

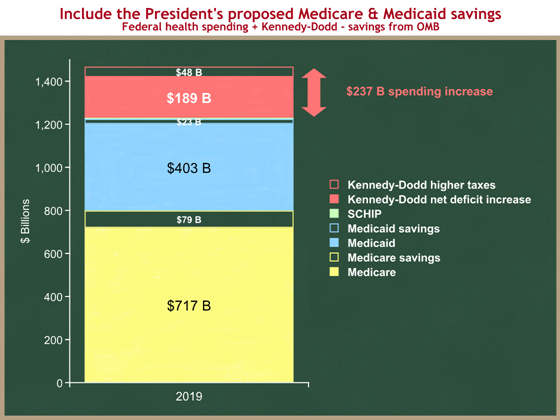

Now let’s focus on the 10th year, the new test defined by Director Orszag. The following graph shows the stacked column just for 2019 from the prior graph, with one addition. While the red on the prior graph showed only health spending, now I want to include the effects of Kennedy-Dodd on taxes as well. Kennedy-Dodd would result in some people buying health insurance outside of employment. If they were to do so, that income would be taxable, and the federal government would collect more in tax revenues. So while Kennedy-Dodd would increase health spending by $237 B in 2019 (and that’s what’s displayed in the graph above), from a budget deficit standpoint, that would be partially offset by $48 B in higher taxes.

I’m not just a low-deficit guy, I’m also a small(er) government guy. I also focus on the medium and long run, where the spending growth rates overwhelm the tax growth rates. So I think the $237 B figure is a better measure of Kennedy-Dodd’s impact. I realize that others don’t share my concern about size of government, and instead focus just on the budget deficit. Even by this measure, Kennedy-Dodd makes things $189 B worse in the 2019, the year chosen by Director Orszag.

- Source: Same as above, page 10 of CBO’s June 15, 2009 letter to Chairman Kennedy.

The Administration, and in particular Director Orszag, argue that the higher health spending from expanding taxpayer-financed health insurance coverage to millions of people will be offset by three factors:

- new proposals to slow the growth of Medicare and Medicaid spending;

- new proposals to raise taxes; and

- in the long run, policy changes that will slow the growth of private health care spending, and which they argue will flow into savings in federal health care programs.

In looking at the 10th year, factor (3) is automatically incorporated into CBO’s estimate of Kennedy-Dodd. CBO gives Kennedy-Dodd no credit to slowing the growth of private health care spending. If they did, those savings would already be built into the above graph. And the Administration does not claim that any of its desired policy changes would produce savings in that 10-year period. If they did, those savings would be built into their projections for factor (1). So for this exercise, we can effectively ignore factor (3).

I will set aside the Administration’s proposed tax increase for the moment. I will return to it.

Let’s now assume that Congress adds to Kennedy-Dodd all of the Administration’s proposed Medicare and Medicaid savings. According to OMB, that’s about $628 B of Medicare and Medicaid savings over the ten-year period. The first half of that was in the President’s budget. The President proposed the second half, $313 B of the total, ten days ago with much hoopla about his commitment to offset higher health spending. I wonder if he knew that his proposals would come up short.

Now it’s unreasonable to assume that Congress will adopt all of these savings proposals, but I’m going to give them and Director Orszag the benefit of the doubt and assume they do.

On the next graph I have erased the parts of Medicare and Medicaid spending that would result from the President’s savings proposals in those programs. These green areas show the effect in 2019 of the President’s proposed Medicare and Medicaid savings.

Why is it so little? Because while the President proposed $628 B in savings over ten years, the amount saved in the tenth year is much smaller. His proposals would reduce federal Medicaid spending by about $23 B in 2019, and would reduce Medicare spending by about $79 B in that same year. That’s a lot, but not compared to the proposed spending increases. The next graph will collapse the stack to eliminate those green gaps.

- Source: “Paying for Health Care Reform,” White House Medicare fact sheet, released June 12, 2009.

- Source: Table S-6 in the President’s budget (pp. 127-128).

- I did not have a 10-year savings stream for the Administration’s second tranche of savings proposals, so I assumed the timing would be distributed the same as in their first tranche. I am confident that’s a reasonable assumption.

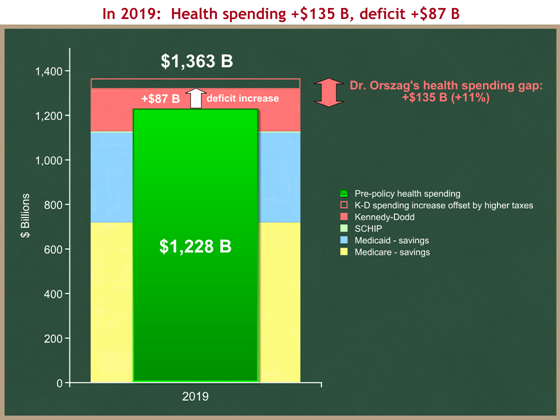

Our last graph will be a before-and-after. The stacked column in back (yellow-blue-red) shows the net effects of current law, plus Kennedy-Dodd, minus all of the President’s proposed Medicare and Medicaid savings. It’s the graph from the last chart, with the bars collapsed together to account for the savings. The green bar in front shows current law spending – it’s the same as the 2019 bar in the very first graph.

You can see the gaps:

- Health spending would be $135 B higher in the tenth year (2019) under (Kennedy-Dodd + President’s savings) than it would be under current law.

- Accounting for the higher taxes that would result from Kennedy-Dodd, the deficit would be $87 B higher in 2019 than under current law.

The Administration has also proposed raising taxes to pay for higher health care spending. The President’s budget proposes to raise taxes for high-income tax filers who itemize their deductions. If Congress were to consider this proposal, it would raise $46 B of revenues in 2019, leaving Director Orszag with a $41 B gap in 2019.

There are two caveats to this proposal:

- It causes the “tenth year” test to lose meaning. In the long run, federal health spending is growing faster than the economy. The revenues raised by this proposal would grow at the same rate as the economy. So closing the 2019 gap through this kind of tax increase means that you still have a long-term health spending problem.

- Congress has rejected this proposed tax increase. They are considering others, almost all of which fall into caveat #1. The only one that does not is limiting or repealing the exclusion for employer-provided health insurance, which grows faster than the economy.

Conclusions

- Kudos to Director Orszag for trying to focus the debate on long-term federal health spending trends.

- Kudos to him for setting a new “10th year test” for health care legislation. I hope the White House doesn’t undercut him in its desire to get a bill to the President’s desk.

- The 10th year test is an imperfect and misleading proxy for our long-term health spending problem, if you use tax increases to close the 10th year gap (excepting the employer-provided exclusion).

- Kudos to the President for proposing additional Medicare and Medicaid savings.

- The Congress will not adopt all of those savings, and they have rejected his proposed tax increase.

- Even if they were to adopt all of his proposed Medicare and Medicaid savings, Kennedy-Dodd would fail the 10th year test by about $87 billion, and it would increase federal health spending by 11% in 2019, or about $135 B.

- As a measure of our Nation’s long-term fiscal problems, the +11% / +$135 B is a better metric.

- Combining Kennedy-Dodd with all of the President’s proposed Medicare and Medicaid savings would make America’s long-term entitlement spending problem much worse than under current law.

Working in Congress: Barking at the ref

Congressional Budget Office Director Doug Elmendorf is doing a great job informing the economic policy debate in a rigorous and unbiased matter. Dr. Elmendorf’s background suggests a different perspective on economic policy from my own. This is unsurprising, given that he was chosen by the chairmen of the House and Senate Budget Committees, Rep. John Spratt (D-SC) and Sen. Kent Conrad (D-ND). He worked at the Fed (a strong signal of first-quality), and in the Clinton Council of Economic Advisers and Treasury Department. Before coming to CBO as director, he was a scholar at the Brookings Institution and worked with the left-side Hamilton Project founded by Robert Rubin.

Dr. Elmendorf is serving admirably as an impartial referee, and is contributing substantially to the economic policy debate.When CBO is at the top of its game, they don’t just produce tables. They explain without bias what the tables of numbers mean.

CBO works for Congress. If you’re writing a bill, you need a “score” from CBO. Working with their sister tax organization, the Joint Tax Committee staff, they will tell you how much spending and taxes will increase or decrease based on your legislative language. If the budget effects of your bill make it inconsistent with the budget resolution passed each year by the Congress, then your bill faces difficult procedural hurdles, and its chance of legislative success declines significantly.

Most CBO staff have advanced degrees, often in economics, public policy, or some specific policy specialty like health or taxes. Theirs is a world of spreadsheets, legislative language, and angry Members of Congress and Congressional staff. Often the CBO staff understand a bill better than the author. CBO staff get barked at a lot by Members of Congress and their staff.

As a government institution, it’s not surprising that CBO staff on average lean a little left. The best evidence of this is that when CBO staff leave, they are far more likely to work for a Democratic member of Congress, or for a liberal think tank like Brookings, the Urban Institute, or the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

At the same time, CBO’s reputation as an institution is predicated on its nonpartisanship, lack of institutional bias, and intellectual rigor. I think that, on the whole, they do as good a job as any of setting aside their personal policy preferences and fulfilling this critical role of an unbiased referee.

CBO is at its best when it is nonpartisan: they say what the evidence demonstrates, no matter who it upsets. This is most difficult for the Director when it upsets the Congressional majority that gave him his job, especially since he is usually of the same political party as they.

Sometimes CBO strays and tries to be bipartisan, rather than nonpartisan. That’s like a referee who tries to even out the game by balancing a bad call he made earlier for one team, by making a bad call now to benefit the other team. I believe the referee should call the play as he sees it, no matter who it upsets, and no matter what the score or history. If the ref makes 5 calls in a row that upset one team, that may not be bias. It may just be that the other team is fouling a lot, or that they have a coach that likes to hector the ref. Some past CBO directors have tried to balance the politics so they get equal heat from both sides. They do this by taking arguments they know are weak and including them to please (or mitigate the anger of) the Member of Congress to whom they’re delivering other bad news. I believe this kind of behavior reflects poorly on the institution. It seems largely absent now.

One of the most effective and best-known CBO directors was Dr. Robert Reischauer in the mid-90s. Put in place by Democrats, he made some hard (and, in my view, correct) budget scoring calls that infuriated the Clinton Administration as it tried to enact the Clinton Health Plan. Dr. Reischauer was publicly savaged by Congressional Democratic Leaders. I imagine the private pressure was even more intense.

Dr. Elmendorf faces a similar situation this year as health care has risen to the top of the Administration’s and the Congressional majority’s agenda. CBO’s rulings are critical to their chances of success, and the pressure already being brought to bear is intense. I have heard reports of specific meetings within the past few weeks in which senior Members of Congress have been directly pressuring Dr. Elmendorf to cut them some slack on scoring. He has withstood that pressure, and the public work CBO is providing is first-rate.

I say this even though I don’t agree with everything they’re producing on this topic. I disagree with some of the judgment calls they are making, in particular, on some of the details of whether “health exchanges” should be counted in the budget. But I think they’re being fair about it. In my first job as a Congressional staffer, I was the health and retirement analyst for the Senate Budget Committee staff under Chairman Pete Domenici (R-NM). I have worked on health budget policy for 15 years, and think I’ve got a pretty good nose for sniffing out biased estimates and analysis. It is now remarkably and admirably absent.

Over the past few weeks, I have been getting a lot of new readers among Congressional staff (from both sides of the aisle). Welcome. For those of you without a lot of experience dealing with CBO, I’d like to suggest some tips for how to work well with the CBO and maximize your chances of getting a score that doesn’t destroy your chances of legislative success:

- Give them a bill to score, or at a minimum a highly detailed policy spec. The more precise you are, the better your score will be. CBO takes a skeptic’s eye to ambiguity and will often not give you the benefit of the doubt when you’re unclear.

- Read what they have written on your bill’s topic before you talk with them. You’ll be smarter, and you’ll get more respect from the analyst for having done your homework.

- Plan ahead. Way ahead. Each analyst and branch has a queue of work. If you’re not on the staff of the committee of jurisdiction, the Budget Committee staff, or in leadership, you will start pretty far back in that queue. Live with it, and plan for it.

- Ask your friendly neighborhood Budget Committee staffer for help.

- Talk with the analyst who is scoring your bill before, during, and after they have worked on it. Ask them if there are parts of your bill that are unclear. See if you can get a discussion going, so you know early if their estimate is headed in a direction that is devastating for you. If it is, ask them to stop so you can fix your bill. See if you can save them time by not making them estimate something, and then starting from scratch.

- Do your homework, and share with the analysts working on your bill. If you have a good study, data or information, share it with CBO, especially if this is a new issue. If you have an expert, set up a meeting with CBO. They will talk to anyone with data and good arguments.

- CBO staff are paid not to care about whether your bill is good policy or bad policy. Don’t be offended. They are paid only to figure out its effects on the federal budget.

- Don’t try to shoot the messenger. It’s usually counterproductive.

- I always had more success asking CBO analysts questions, than trying to change their minds. I would try to figure out how they approach a score, and why they thought my bill would produce the budget effect that it did. Sometimes you get scored with a big budgetary effect for something that is tangential to your core purpose. The better you understand this, the more you can adapt to get your score down. CBO analysts generally react much better to incisive questions than they do to screaming.

- I always found I had much better success by being respectful and polite than a jerk. I don’t think it directly affected the analysis they produced for me, but it did get me better response times, and more useful information that wasn’t in the formal written estimate. Besides, if you act like a jerk, then you are a jerk. Who wants that?

Dr. Elmendorf and the CBO staff face a test similar to that faced by CBO under Dr. Reischauer during debate on the Clinton Health Plan. They have so far withstood the pressure with aplomb, but the real pressure is just beginning.

(photo credit: z04b_57 Growling Gizmo Dog, Vancouver 2005 by CanadaGood)

Kudos to the President for proposing to scale back terrorism reinsurance

Kudos to the President for his proposal to scale back the subsidy for terrorism reinsurance. I wish he had gone all the way to eliminate this program during this term, but I’ll take the partial win.

After the 9/11 attacks, parts of the market for insurance against terrorist attacks evaporated. Insurers rely on statistical data to determine the chance of a future terrorist attack, and therefore the chance that they will have to pay a claim. Insurers were no longer able to estimate the chance that the Empire State Building, or a new stadium, would be attacked, and so they were unwilling to sell terrorism insurance for these kinds of high-value terrorist targets.

This caused further problems, because some real estate developers could not get bank loans without insurance against a terrorist attack.

In 2002 President Bush proposed, and the Congress created (on a strong bipartisan vote) a terrorism reinsurance program, known as the Terrorism ReInsurance Act (TRIA). The government acted as insurer to insurance companies against the risk of an attack on property by foreign terrorists. This was supposed to be a temporary program to fill the gap and allow real estate construction to proceed, while the insurance industry had time to recoup its losses from 9/11 and redevelop new estimates that would allow it to reenter this market.

The program contained an implicit taxpayer subsidy. Since we have not had a terrorist attack since 9/11, there have been no actual government outlays, but the subsidy exists nonetheless. Insurers had higher profits because they don’t have to buy reinsurance on the private market. They relied on the government program instead.

The insurance industry built a bipartisan coalition of Members to extend TRIA and maintain the implicit taxpayer subsidy.The industry has now had more than seven years to re-estimate probabilities and rebuild their financial cushions. There is no longer a need for TRIA, but the insurance industry is extending the subsidy because it can.

The original TRIA law created a two-year program. We tried to eliminate it at the end of 2004, but an overwhelming bipartisan majority decided to extend the program for three more years, until the end of 2007. In 2007 we again tried to eliminate TRIA, and an even stronger bipartisan coalition extended TRIA for seven more years. It is now scheduled to expire at the end of 2014, although I won’t hold my breath.

Each time we were able to scale back the subsidy by raising the deductibles and charging the companies (effectively) higher premiums. In 2007, however, the industry was able to expand the program’s scope to include domestic terrorist attacks. They failed (thankfully) to expand the program to cover life insurance policies.

The market for terrorism insurance and reinsurance would function properly if the government were no longer involved in it. The President deserves kudos for proposing to further increase the deductibles and thereby scale back the implicit taxpayer subsidy, and for proposing that the program sunset after 2014. I wish he had proposed to eliminate it immediately — we certainly could use the scorable savings.

In the grand scheme of things, $300M — $400M per year is small compared to a $2+ trillion annual budget, and as I noted, that’s an implicit subsidy that has so far involved no actual government outlays. We should eliminate this program because we can — the need for this program no longer exists, the market can function without it, and taxpayers should not be subsidizing the insurance industry.

There is an opportunity here for a conservative Member of Congress or think tank to work with the President on a good (if small) free-market policy reform. It will be you and the President against corporate welfare for the insurance industry and an overwhelming bipartisan majority of Congress. Sounds like a fun fight.

A tough call

I spent a few hours this morning reading through all 1,500 comments posted in the three months since this blog went live. I am overwhelmed by the comments and commenters.

Before launching, I seriously debated whether to take the risk of allowing comments. I am now enormously gratified that I did so.

On the whole, the comments are intelligent, thoughtful, and respectful. I thank all who are contributing to an impassioned debate and elevating the level of discussion.

I made a tough decision this morning. For the first time, I banned a commenter from future posting. After three months, I am still a fledgling blogger, so this was a tough call for me.

Substantively, it was easy. This commenter had clearly and repeatedly violated item #2 of my comment policy (emphasis added)

Please refrain from personal attacks. Treat this as a discussion among friends. Debate vigorously, and play nicely, please. If necessary, I will moderate comments as needed to keep the discussion civil.

I worked in the United States Senate for 7+ years, and developed tremendous respect for the Senate’s rules of decorum in speaking on the Senate floor. Senators must always address the Chair, rather than speaking directly to each other. Ad hominem personal attacks are a violation of the Senate rules. Members from radically different ideological perspectives refer to each other as, “My good friend, the Senator from

[State], even when they despise each other.” Over time, this artifice creates an environment of vigorous, impassioned, yet civil debate that focuses on policy questions. It infrequently descends into gutter attacks. I hope to create the same environment here, and will do what is necessary to enforce a polite discussion. If you’re a jerk, I’ll boot you. Permanently.While going through the comments this morning, I redacted personal attacks and insults directed from one commenter to another, as well as most instances of gross vulgarity. While this commenter had posted almost 100 comments, many of which contributed significant substance, more than half of all violations were posted by this one commenter. I had posted multiple warnings about the tone and policy violations (and not just by him/her) over the past 10 days or so, warning that I would be banning those who violated my policy.

This person is now permanently banned from commenting on my blog. I tried to notify him directly in advance, but his email address bounced back.

What made this difficult is that his (her?) comments are intelligent and provocative. Aside from the tone and personal insults directed at other commenters, he contributed a challenging and different perspective to a vigorous debate on my health posts. I value highly that intellectual diversity, and am sorry to lose it going forward.

I want to reiterate item #1 of my comment policy:

I welcome, invite, and enjoy substantive comments from any ideological perspective. Please contribute to the discussion. I welcome those who disagree with me.

I think and hope that I can attract more commenters with his perspective on policy, which differs from my own. Had I not made this decision, I feared that I would soon lose and be unable to restore the environment of impassioned yet respectful debate that has otherwise been growing here.

Again, I thank all those others who are contributing to the debate here, and especially those who disagree with me.

Senator Conrad’s co-op health insurance proposal

Senator Kent Conrad (D-ND), Chairman of the Budget Committee and a member of the Finance Committee, has floated an idea he is trying to position as a compromise between those who want a government-run “public option” and those who oppose it.Senator Conrad’s theme is to facilitate the creation of “non-profit, non-government” health plans, but in which the government sets certain standards. The public expression of his idea is sufficiently vague that everyone can hear what they want to hear. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D-MT) has said that he supports the idea.

As I understand it, Senator Conrad’s proposal would have the government create a new entity with a federal charter.Taxpayers would provide a few billion dollars to that entity. While this entity would be called the COOP, the acronym does not stand for “cooperative,” and the entity would not be a cooperative. The purpose of this new national organization would instead be to help form nonprofit health plans in each state. The key concept is that this new organization would have the authority to approve a nonprofit health plan to operate in a state, even if that State’s insurance commissioner said no. (As I understand it, the Conrad proposal dances around explicitly stating this ultimate hammer as bluntly as I have, probably in hopes of avoiding the wrath of the State insurance commissioners, who are often quite powerful.) In addition, this new entity could provide seed capital to new nonprofit health plans. The COOP would be a national chartering and financing organization.

The President would pick, subject to Senate confirmation, the people who run that new entity, but it would be a private nonprofit organization. This allows Sen. Conrad to say that it is “non-profit, non-government,” but the taxpayers are providing the initial capital, the government would set certain rules for this new entity, and the government is picking management.Under these conditions, the legal structure is largely irrelevant. It looks, walks, and quacks like a Government Duck.

In creating a new national insurance chartering entity, Senator Conrad is attacking a legitimate problem here, albeit with a solution that I oppose. When government mandates that health plans cover certain diseases, providers, or treatments, that causes premiums to increase. When government mandates that health plans charge everyone the same premium regardless of their age or health status, that also causes premiums to rise for most people. Many state legislatures and state insurance commissioners have gone hog-wild on insurance mandates. It is politically popular to mandate that a health plan must cover disease X, or not exclude person Y. These mandates accumulate, resulting in high premiums and all their knock-on effects:lower wages for those with health insurance, more uninsured people, and higher costs for government plans that must also comply with the mandates.

By giving this new entity the authority to bypass the State insurance regime for new nonprofit plans, Senator Conrad would create a new market for nonprofit plans with lower premium costs. So far, that’s good, but the Conrad plan then runs into three problems:

- If it’s OK to bypass state insurance mandates for these new nonprofit plans, why isn’t it also OK to do so for all those Americans who now get their health insurance from a for-profit insurance company? The Conrad plan appears to create a distinct market advantage for one legal structure of health plan. Ultimately, what we should care about are the people who buy health insurance, not the legal or governance structure of the firm offering it to them. It would be unfair to the more than 100 million Americans who now get their insurance from a for-profit firm to say, “You can get lower premiums if you leave your health plan, because Congress thinks that nonprofit plans are somehow morally superior to for-profit plans.” Remember that nonprofit organizations make profits, they just distribute them differently. Where a for-profit firm distributes its profits to its owners, a nonprofit firm distributes them to some combination of its employees, customers, and whoever provided the startup capital.

- Sen. Conrad’s colleagues on his Left want to change his idea. Rather than having the new entity be an alternate approval mechanism for new nonprofit health plans, Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) says the new entity should be a new national nonprofit health plan itself. This, of course, would be the public option, but with a non-governmental logo on the letterhead. The government would be financing the new entity, bearing the risk of unexpected payouts, determining premiums and benefits, and setting provider payment rates. The Schumer variant of the Conrad idea is the public option.

- If you were willing to create an unlevel playing field that advantaged nonprofit plans, as Sen. Conrad suggests, then you run the risk that the government will show up a year or two from now with “just a few more rules” for the new entity to impose on plans. Since the new Conrad entity in effect becomes a new national health insurance chartering organization, every disease lobby group will immediately shift their focus to placing new requirements on the new entity. You will start to see an endless sequence of amendments to legislation, in the form of, “The new nonprofit chartering entity shall require that all chartered plans require coverage of ________________.” They’ll start with the diseases that affect kids and pregnant women, because those are the hardest to vote against. Alternatively, legislation could give the Executive Branch the power to set standards or goals for the chartering entity, the way that HUD sets low-income housing goals for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

It’s not clear which of these outcomes is worse. I think everyone is familiar with the arguments against a pure public option.They apply equally to the Schumer variant of Senator Conrad’s idea.

A two-tiered structure, in which nonprofit health plans have a market advantage over for-profit plans, would be hugely disruptive. Individuals and employers would have a tremendous incentive to dump their current health plan in favor of a new one chartered by this new entity. To the extent that employers made this choice on behalf of their employees, it would conflict further with the President’s commitment that you can keep the plan you have now.

I fear that, like the public option, the Conrad option would crowd out private health insurance. Government would provide low-cost capital. Government would impose rules to suit the Congressional or Executive Branch whims of the moment. The ability to bypass state insurance commissioners would mean these new nonprofit plans, regulated by the new entity, would crowd out the existing market of private plans.

If you believe that replacing our current market mix of for-profit and nonprofit health plans with the government is a good thing, then go for the public option.

If you believe that we should replace our current mix of health plans with nonprofit plans regulated by this new entity, and you believe that the government will relinquish control of these new plans in a few years as Sen. Conrad suggests, then go with the Conrad option.

Please don’t misconstrue this as me defending the for-profit health plan that you may dislike. I am instead arguing that, whatever your view of today’s private health insurance market and private for-profit plans, more government involvement as proposed by Senators Conrad or Schumer will make things worse.

(photo credit: Wikipedia)

The President overpromises on keeping your health insurance

Here is the President this past Monday, speaking in Chicago to the American Medical Association:

So let me begin by saying this: I know that there are millions of Americans who are content with their health care coverage … they like their plan and they value their relationship with their doctor. And that means that no matter how we reform health care, we will keep this promise: If you like your doctor, you will be able to keep your doctor. Period. If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan.Period. No one will take it away. No matter what. My view is that health care reform should be guided by a simple principle: fix what’s broken and build on what works.

The President overpromised. So far the best he can deliver is, “If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan, as long as you’re not one of the 10 million people whose employer will decide to stop offering you health insurance through your job.” I think that loses some of its rhetorical punch.

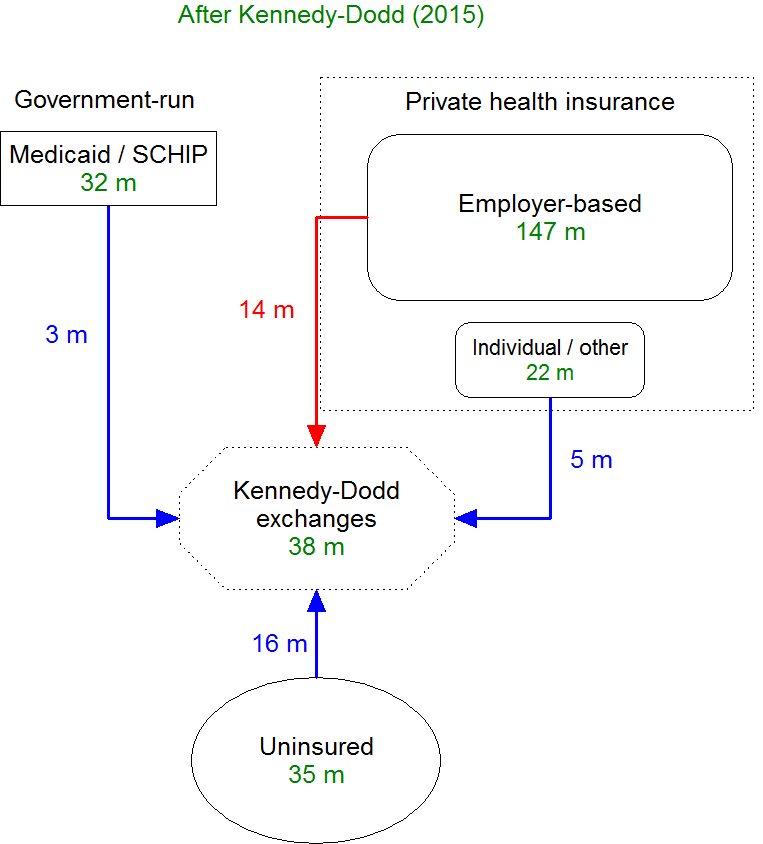

Let’s look at what the Congressional Budget Office says would happen under the draft Kennedy-Dodd health care bill. Here’s the diagram I showed you yesterday. The relevant arrow is in red.

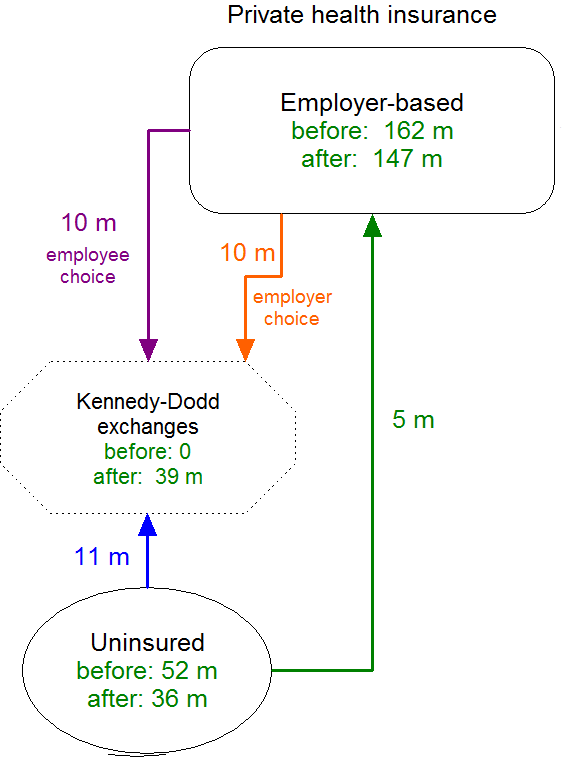

That 14 m number was a net figure. It was close, but not entirely correct. CBO Director Doug Elmendorf has posted a helpful follow-up on his blog which “unpacks” that red arrow into its component parts. Kudos to him for doing so. I am going to expand part of the above diagram using Dr. Elmendorf’s new information. These new lines below replace and correct the “14 M” red arrow and the “16 M” blue arrow from yesterday’s diagram above. I also have to shift from 2015, which I used yesterday, to 2017, which Dr. Elmendorf uses in his post. The two-year difference is trivial and does not change the underlying substantive point.

Director Elmendorf explains that, under the Kennedy-Dodd draft, 20 million people would leave employer-based insurance and instead use the new subsidies to buy insurance through an exchange.

10 million people, represented by the purple arrow I have labeled “employee choice,” would make this choice individually and voluntarily. Here’s Director Elmendorf:

Some individuals would have insurance coverage available from their employer, but would also have an option to obtain subsidized insurance from an exchange. That opportunity would exist for people whose incomes were sufficiently low – and the cost of employer-sponsored insurance sufficiently high – so that the insurance would be categorized as “unaffordable” under rules that would be set by the Secretary of Health and Human Services. … By CBO’s estimate, about 10 million people with this choice would opt to obtain insurance from exchanges rather than from their employer.

Another 10 million people, represented by the “employer choice” arrow, would lose their current employer-based insurance because their employer stops offering it. With that option vanishing, these people would then take advantage of the new subsidies and buy health insurance through an exchange. Here is more from Dr. Elmendorf:

The availability of subsidized coverage in the new insurance exchanges would be an attractive option for many lower-income workers. As a result, some employers would decide not to offer their employees health insurance coverage, opting instead to provide other forms of compensation. CBO estimates that about 10 million individuals who would be covered through an employer�s plan under current law would not have access to that coverage under the draft legislation because some employers would choose not to offer it.

Finally, yesterday I got the blue arrow from “Uninsured” to “Exchanges” wrong. I think I have it right now. 11 million people who were previously uninsured would now buy health insurance through an exchange (blue arrow). Another 5 million people who were previously uninsured would be newly covered by employer-based coverage (green arrow). Here’s Dr. Elmendorf one more time:

Finally, approximately 5 million more individuals would obtain employer-based coverage under the proposal (compared with the number under current law) either because they worked for a firm that newly began to offer coverage as a result of the legislation or because they decided to enroll in an insurance plan that the employer would offer under current law but which they would not select in the absence of the legislation. (Some workers would value an employer’s offer of insurance and be more willing to sign up for it because of the legislation’s requirement for individuals to have insurance; some employers would begin to offer insurance to accommodate employees’ desires and to take advantage of the subsidies that would be provided for some small businesses.)

The net effect of the blue and green arrows is still a decline in the number of uninsured by 16 m, but now it’s split into two parts. And the net decline in employer-based coverage is still the 14 million from yesterday, but that’s the result of (10 purple + 10 orange – 5 green = 15 red), where the 15 vs. 14 is from shifting from 2015 to 2017.

Losing employer-based coverage

While I am flagging it as substantively significant, it may surprise you that I am not going to criticize the Kennedy-Dodd bill for the harm done to these 10 million people who would lose their employer-based coverage through “employer choice.” This is a painful but unavoidable consequence of (partially) leveling the financial playing field between employer-based and individually purchased health insurance.

I strongly oppose the Kennedy-Dodd draft for reasons that I have previously described. But leveling this playing field is a good thing. Rather than creating a new spending program, I would completely level the playing field by eliminating the tax exclusion and creating a new tax preference for health insurance that was independent of how you bought it. When President Bush proposed such a policy in 2007, we faced the same effect that I describe here for Kennedy-Dodd. Some people are hurt because they would lose something they value and now have. If you design your plan right, far more people are better off, and you have to decide whether the tradeoff is worth it.

So while I am tempted to attack Kennedy-Dodd for this reason, my desired reform suffers the same downside. It is an unfortunate but unavoidable consequence of moving away from a system so heavily biased toward employer-based insurance. There are plenty of other reasons for me to oppose Kennedy-Dodd.

Team Obama’s political and legislative mistake

At the same time, this exposes a devastating tactical error by the President’s team. They put their boss out there saying:

If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan. Period. No one will take it away. No matter what.

Under the Kennedy-Dodd bill, that is not true for 10 million people. And the same will be true for any other bill that levels the playing field between employer-based and individually-purchased health insurance, which means any bill that offers subsidies to buy insurance outside of your job. You cannot avoid this problem. The mistake is not the unavoidable policy consequence. The mistake was making a Presidential promise that cannot be kept.

The Administration and its Congressional allies can mitigate but not eliminate the 10 million number. They can reinstate the employer mandate that Kennedy left out of the draft he gave to CBO, and I assume they will do so. By raising the costs on employers of dropping coverage, the 10 million number will go down. But to get that 10 million down a lot, they would have to make the financial penalty on employers for dropping coverage exceedingly high, and they would have to be explicit in their legislative language for a skeptical CBO to give them credit for it. The higher that penalty, the fiercer the opposition from employers. And no matter how high they raise that employer penalty, I expect CBO still would not take the 10 million figure down to zero. The Administration and its allies have boxed themselves into a corner.

The President made and repeated a sweeping promise, that no one would lose the health insurance and doctor they have now. This is smart politics and good legislative strategy as long as it doesn’t backfire. CBO is now on record that the Kennedy-Dodd draft does not fulfill the President’s promise. That’s an immediate problem for Kennedy and Dodd, and a near-term problem for the Administration, which now has to figure out whether they support an excruciating employer mandate to get the 10 million number down, and how they’re going to mitigate this problem for other bills that will have the same ugly feature. Even if they do, I expect that any solution will still violate the pledge for millions of people, although fewer than 10 million.

Had the President not made this statement, the Administration would have a policy problem with an obvious solution: get the number down through the employer mandate, and argue that those who are hurt are far outnumbered by those who are helped. Instead, they now have this policy problem, combined with a “Presidential promise” problem.

The President’s advisors never should have let him make this promise that he cannot keep.

(photo credit: whitehouse.gov)

My CNBC interview on the President’s financial regulatory reform plan

Erin Burnett interviewed me this afternoon on CNBC’s Street Signs about the President’s new financial regulatory reform plan. Thanks to Erin and her producer Robert Hand for having me on the air to discuss such an important subject.

CBO scores the Kennedy-Dodd bill

The Congressional Budget Office has released a preliminary estimate (“score”) of the draft Kennedy-Dodd health care bill.Some in the press are reporting that this is a “$1 trillion bill.” This poorly explains the true budgetary impact of the bill for several reasons. The bill would increase spending by more than $1.3 trillion (that’s “thirteen hundred billion dollars”) over ten years, and even that understates the impact because the bill phases in over the first five years.

I explained last week that the bill is incomplete. I expect a later version of this text will be marked up by the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) committee, and then combined on the Senate floor with a companion bill marked up by the Senate Finance Committee. Even in its final form the HELP Committee text will be only half a bill. I further expect the HELP Committee bill will end up increasing the budget deficit, while the “pay-fors” (offsets) will come from the Finance Committee bill, which it appears will raise taxes and cut Medicare and Medicaid spending.

New health care entitlement spending

CBO has estimated the effect on the federal budget of the new subsidy component, which I described last week:

People from 150% of poverty up to 500% (!!) would get their health insurance subsidized (on a sliding scale). If this were in effect in 2009, a family of four with income of $110,000 would get a small subsidy. The bill does not indicate the source of funds to finance these subsidies.

There are at least six other major components of the bill that have not yet been scored by CBO. Part of this is due to the time crunch, but most of it is because the Kennedy-Dodd staff have not yet given CBO specific enough legislative language for CBO to do their thing.

- The budgetary effects of neither the individual mandate nor the employer mandate are included in this score. I think CBO will find these provisions would raise revenues for the government and reduce the deficit. While the leaked draft of Kennedy-Dodd was specific about the employer mandate, the official version has just the placeholder language, “Policy under discussion.” Both mandates leave wide discretion for the Secretaries of Treasury and HHS to create a level and structure of taxation “to accomplish the goal of enhancing participation in qualifying coverage.” It is extremely difficult for CBO and their tax counterparts, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) staff, to estimate something like this.

- The estimate does not include the budgetary cost of expanding Medicaid to childless adults with income below 150% of the poverty line. I expect that this will add hundreds of billions of dollars to the cost over the next decade.

- It does not include the requirement that health plans define “children” as dependents up to age 27. I expect this will raise costs.

- It does not include the effects of the Medical Advisory Council’s ability to define benefits, or the requirements that plans rebate premiums to the insured. I think this too will raise costs.

- It does not include the budget effect of having a “public plan option.”

- There are a bunch of other programs in the bill, including a new disability program and lots of new public health programs.

What we have is a score of two provisions — the new subsidies for people between 150% and 500% of poverty to buy health insurance, and subsidies to small businesses with low-wage employees. We can learn a lot from the table on page 10 of CBO’s estimate. Press coverage is focusing on the “one trillion” number for the net deficit impact, making the common mistake of losing important information by ignoring the gross components of that net number. I am more concerned with the size of the new health care entitlement spending, which is $1.3 trillion over the next ten years.

| 2010-2019 total | |

| Exchange subsidies | 1,279 |

| Small business subsidies | 60 |

| Payments by uninsured individuals | -2 |

| Medicaid/SCHIP outlays | -38 |

| Tax effects on deficit | -257 |

| Net deficit impact | 1,042 |

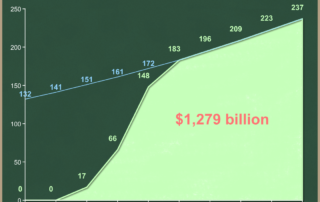

95% of the spending, $1,279 billion over the next ten years, comes from the new subsidies for individuals. This spending does not begin until year 3 (2012), and it’s not fully effective until year 6 (2015). This is a normal effect of implementing such a huge and complex policy — it takes several years to phase in. While the $1,279 billion represents the actual effect on the federal budget of this bill, we can see that the phase-in reduces the cost quite significantly. The green area is 71% of the area under the blue line, which is my estimate of the hypothetical cost of a bill that were it fully effective on day 1. I am not arguing that the “real” cost is the area under the blue line, but instead that focusing only on the 10-year total disguises the true long-term cost of this new entitlement spending. The Kennedy-Dodd draft creates new health spending entitlements that would grow 6.7% per year, faster than our economy, which CBO projects to grow about 4% per year (nominal) in the long run. This means the new health entitlement spending would eat up a larger share of the economy over time.

Effect on private sector spending

CBO has not estimated the effect of this bill on private sector health care spending. That’s not their core mission, but I hope they do so when they have a more fully specified bill. It is a critical metric identified by the President as one of his key tests for an acceptable bill, and it’s a core element of my four-part test for measuring health care cost control.

Effect on health insurance coverage

I will let the pictures tell the story. Here is a before and after of the effects of implementing the Kennedy-Dodd bill. I have chosen 2015, the first year in which the subsidies would have their full effect. Pictures for succeeding years would look similar. I have written before that I think the 51 million figure (now 46 million) overstates the problem to be solved.

And here is the effect of the Kennedy-Dodd bill:

You can see that Kennedy-Dodd would mean that 16 million otherwise uninsured people would get health insurance through the new exchanges, as a result of the subsidies.

In addition, another 22 million people who will otherwise have health insurance will take those subsidies. Three million are a shift from one taxpayer-financed program (Medicaid or SCHIP) to another (the new exchanges). But CBO estimates that 19 million people who are now using their own resources will take advantage of the new subsidies and get health insurance through the exchanges.

This is the problem with creating a new subsidy for something that people are already doing. Analysts say that the new taxpayer subsidies “crowd out” private spending. These people are better off, in that they now have funds available to spend on other things. But if the goal is to reduce the number of uninsured, it is inefficient because half the people benefiting from the new spending are substituting public dollars for private ones.

This makes the cost per newly insured numbers look bad. If you look at just the effects on spending, it’s more than $11,400 per newly insured person. Even if you take into account the higher tax revenues that result from the movement out of employer-based health insurance, the net cost to the taxpayer is still more than $9,100 per newly insured person.

I will soon apply my four-part test to this preliminary Kennedy-Dodd draft, and will update these estimates as the policy develops.

(photo credit: Referees in the Tunnel by Scott Abelman)