Senator Kerry’s tax on health insurers

A Hill friend asked me what I thought of Senator John Kerry’s (D-MA) idea to tax health insurers if they charge above a certain amount for health insurance.

As I understand it, Senator Kerry’s idea is to tax health insurers. The tax would be:

tax on an insurance company = 35% X (the premiums they charge their customers above $25,000 for a family policy)

So if an insurer sells a family policy for $15,000, there is no new tax. If instead the insurer charges $27,000 for a family policy, the insurer would pay Treasury 35% X ($27,000 – $25,000) = $700 on this one policy.

In reality, the calculation would be done in the aggregate. The insurer might sell insurance to a company for 1,000 super-expensive family policies for $27,000 each, and pay Treasury 1,000 X $700 = $700,000.

I believe the insurer would pass most (all?) of these costs along to the purchaser of insurance. We used to have a 3% telephone excise tax that was technically imposed on phone companies. Those companies just added it to your bill and passed the taxes through to their customers. I believe the same would happen here, so Senator Kerry’s proposal would result in higher premiums for those who now buy very expensive health insurance policies.

You should know that $25,000 is incredibly high. Average annual health insurance premiums for a family were about $15,000 in 2007. I assume they’re in the $16,500-ish range now.

I had drafted a long wonky post that waded into the details of this, but it got too weedy. I will therefore gloss over all the detail and just offer my conclusions, which are highly personal. Sometimes I’m trying to convince you of facts or analysis that I am convinced is analytically and provably correct. Here I am instead offering a personal policy judgment. For what it’s worth, here are …

My conclusions on the Kerry proposal

- My first choice would be to repeal the current law tax exclusion for employer-provided health insurance and replace it with a flat standard income tax deduction for the purchase of health insurance.

- I think capping the exclusion at a high premium level, like the $25K being discussed by some Finance Committee members, is silly, wimpy, and weak. I also think it’s foolish legislative politics, because you get probably half the political cost of repealing the exclusion, but only a small fraction of the policy benefit. But if they used the revenue to do a standard tax deduction, I would support it as better than nothing (if they index it correctly going forward). I’d be willing to discuss using the revenues raised for a flat health insurance tax credit, too.

- The Kerry proposal is quite similar in effect to capping the individual exclusion at $25K. It’s not identical, because the 35% applies to everyone regardless of income. It’s klunky and inefficient and far less transparent than just capping the exclusion, so I think it’s only marginally better than nothing, and only if the revenues raised are used to cut other taxes. The mechanism also muddies the incentives and creates market distortions, which further undermines my enthusiasm.

- I think the Kerry proposal is designed to have a similar effect to capping the exclusion, without provoking the same union opposition that has killed most Congressional Democrats’ ability to support a capped exclusion. This surprises me because the effects are so similar (but not identical). If unions oppose capping the exclusion because they don’t want to raise taxes on their members’ health insurance premiums, why does Senator Kerry think they would be OK with a policy that will result instead in higher health insurance premiums and lower wages by roughly the same amount?

- Any of these three options would mean more tax revenues for the government. I draw a bright line that any higher taxes should be returned to the private economy through lower taxes. I would do that through a standard income tax deduction for the purchase of health insurance. In the common raw political vernacular, I oppose “tax-and-spend” policies even if they are deficit-neutral. So I could be OK with a capped exclusion, and I could swallow the Kerry tax proposal, but only if the revenues are not funneled into a new government spending program. This is where the Finance Committee closed-door discussions leave me behind: all of the discussions are higher-taxes-for-more-spending, and I strongly oppose that.

- Senator Kerry appears to be trying to come up with something that raises revenues in a way that Republicans can swallow, and that functions similarly to (but less effectively than) a capped exclusion, while tiptoeing past the unions. Clever non-transparent policies with muddled incentives are generally bad ideas with even worse unintended consequences. And I strongly oppose the idea if the higher taxes are used to expand government health spending programs (like Medicaid).

While I appreciate the legislative creativity that appears to be behind Senator Kerry’s attempt to broker a legislative compromise, I would oppose this policy change. I’m just not a tax-and-spend guy.

(photo credit: kerry.senate.gov)

20 questions for the President’s press conference

President Obama is scheduled to hold a press conference tomorrow (Wednesday) evening at 8 PM EDT.

I hope the questions are better than the one asked by Jeff Zeleny of the New York Times at the President’s 100-day press conference on April 30th:

During these first 100 days, what has surprised you the most about this office, enchanted you the most about serving in this office, humbled you the most and troubled you the most?

In case any members of the White House press corps are looking for more rigorous questions focused on economic policy, I offer the following for your consideration.

Economy

- The U.S. economy has lost 2.64 million jobs since you took office. The unemployment rate is 9.5% and rising. The good scenario is one in which the unemployment rate begins to decline early next year. The Vice President said your Administration misread the economy. You said you had incomplete information when proposing the stimulus. Yet you have said you would not change anything about the stimulus if you could. If the facts have changed, why doesn’t it make sense to change your policy?

- Last month’s jobs report was the first since you took office that was worse than the prior month. Do you think the economy is getting stronger or weaker right now? If the next jobs report gets still worse, will you re-evaluate the need for a change in fiscal policy?

- Do you maintain your promise not to allow taxes to be raised on people earning less than $250,000 per year? Will you insist that health care legislation conform with this commitment?

- Chrysler and GM have exited bankruptcy. Are U.S. taxpayers done subsidizing these firms? What is your exit strategy from taxpayers owning much of GM and Chrysler?

- You proposed spending money from the TARP to prevent foreclosures, help small businesses, and to buy toxic assets from banks. In June CBO said they had found no evidence that any money has been spent for any of these programs. How many foreclosures have been prevented, how many small businesses have received loans from, and how many toxic assets have been purchased?

Health care

- You have insisted that health care reform “bend the cost curve down.” CBO Director Elmendorf says the bills being debated would instead raise the health care cost curve and would increase long-term budget deficits. Will you continue to insist that health care reform not increase the deficit?

- Your Administration has said that health care reform is the key to addressing our long-term budget problem. Yet you have adopted a lower standard, that health care reform legislation simply does not make our deficit problems worse. If health care reform leaves the unsustainable budget situation unchanged, and since CBO says your budget would result in nine trillion dollars of new debt over the next decade, then how else do you propose to deal with the projected explosion of government debt over the long run?

- You have said transparency is a top priority. Yet you are calling on Congress to pass a trillion-plus dollar spending bill before CBO has had time to estimate its full effects. In addition, your Administration is delaying release of the new economic projections and deficit estimates until after Congress votes on this massive new spending bill. Will you commit now that you will not ask Members of Congress to vote on this massive new spending commitment until your Administration has met its legal obligation to provide an updated economic forecast and deficit projection, and until CBO has provided Congress with transparent and complete analysis of the bill?

- On June 15th you said, “If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan. Period. No one will take it away. No matter what.” Yet CBO says these bills would cause a few million Americans who now have employer-provided health insurance to lose it, as their employers would try to push costs and people onto taxpayer-subsidized programs. Last Thursday in New Jersey you seemed to redefine your promise when you said, “When I say, ‘If you have your plan and you like it,’ what I’m saying is the government is not going to make you change plans under health reform.” And at your televised forum, you said, “If you are happy with your plan, and if you are happy with your doctor, we don’t want you to have to change.” Do you believe your first promise was too strong?

- In a February 2008 debate with then-Senator Clinton you opposed an individual mandate to buy health insurance. In that debate you said, “In some cases, there are people who are paying fines and still can’t afford it, so now they’re worse off than they were. They don’t have health insurance and they’re paying a fine. In order for you to force people to get health insurance, you’ve got to have a very harsh penalty.” Now you are supporting a bill that would force people to buy health insurance, and that CBO says would still result in eight million people not having health insurance and paying higher taxes. How do you explain to those eight million uninsured people why you now support the mandate and “very harsh penalty” they would have to face, and which you opposed during the campaign?

- Experts across the policy and political spectrum say that repealing or limiting the tax exclusion for employer-provided health insurance is a good way to bend the health cost curve down. Some powerful unions oppose this change. Your position has so far been ambiguous. Do you think this change would be good policy? Are you willing to support it if it attracts Republican votes?

- Your party controls the White House, has a 38+ seat margin in the House, and has the 60 Senate seats needed to overcome any filibuster. How can Republicans be holding up health care reform?

- Most members of Congress who oppose these health care bills argue they have a better way of reforming health care, such as the Ryan-Coburn bill. Why is it fair to accuse them of defending the status quo? Can you name a Member of Congress who has explicitly argued for the status quo, rather than just arguing against your preferred alternative?

- You campaigned against Washington special interests and have accused them of attempting to block health care reform. Yet your Administration has negotiated and supported deals made behind closed doors with some of these same interests, and you have announced those deals here at the White House flanked by Washington lobbyists representing HMOs, drug companies, hospitals, doctors, unions, and nurses. How is this consistent?

Energy & Climate change

- The Indian government told Secretary Clinton that India will not agree to limit its carbon emissions. The Chinese have sent the same signal. Are you willing to sign a new climate agreement that does not contain binding commitments by China or India to reduce or slow the growth of their emissions?

- Does it make sense for the U.S. to impose higher energy costs on American workers and manufacturers if the two largest developing economies are unwilling to slow their emissions growth? Won’t that just disadvantage American workers with little reduction in future global temperatures?

- If the Senate cannot pass a cap-and-trade bill this fall, will you ask Congress to send you a smaller clean energy technology bill before you go to the global climate change discussions in Copenhagen this December?

- Do you support the expansion of nuclear power in the U.S.? If so, what are you doing to encourage it? And where are you going to store the nuclear waste, given the strong opposition of Senate Majority Leader Reid to storing it in Nevada’s Yucca Mountain?

Trade

- The top Democrat and Republican on the Senate Finance Committee have called for you to submit to Congress for their approval the signed Free Trade Agreements with U.S. allies Colombia, Panama and South Korea. Why have you not submitted them to Congress? When will you do so?

- At the G20 and G8 Summits you joined other leaders in renouncing protectionism and committed to concluding the Doha Round of global trade talks. What steps are you taking to roll back protectionist measures the U.S. has taken, such as Buy America, and what concrete steps are you taking to advance the Doha Round?

The President and Congress are considering changes in economic policy that would have massive effects if adopted. I hope the White House press corps asks rigorous questions that can better inform the economic policy debate.

(photo credit: whitehouse.gov)

Hennessey’s health care reform plan

I will be on CNBC’s Street Signs this afternoon at 2 PM EDT. Governor Howard Dean and I will be discussing health care reform with host Erin Burnett.

Update: We’ve got video.

Wednesday the President spoke in the Rose Garden about health care reform. He said:

<

blockquote>And

So make no mistake, the status quo on health care is not an option for the United States of America. It’s threatening the financial stability of families, of businesses, and of government. It’s unsustainable, and it has to change.

I agree with all of this, except “those who oppose our efforts should take a hard look at just what it is that they’re defending.”

I strongly oppose the House tri-committee bill and the Kennedy-Dodd HELP committee bill. I do not support the status quo. I want different and even more aggressive reform than is being proposed in Congress. It is unfair to characterize those who oppose the current legislation as opposing all health care reform, or as defenders of the status quo.

I therefore want to be explicit about what I support. I propose Congress adopt the following plan instead of the legislation they are now considering.

A full description of a health care reform bill would probably take a few thousand words. Today I instead offer just the basic description of what I propose. This is not as polished or detailed as I would like, but it’s the core, and I would like to get it out there before our CNBC discussion today. I am going to label this v1. I may tweak it a bit over time, but the core will not change. If you follow the health care debate closely, many parts of this will look familiar. I may flesh out details in the future.

This should be a debate among alternatives, not “Are you for health care reform or the status quo?”

Keith Hennessey’s health care reform plan (v1)

Do:

- Replace the tax exclusion for employer provided health insurance with a $7500 (single) / $15K (family) flat deduction for buying health insurance.

- Allow the purchase of health insurance sold anywhere in the U.S.

- Make health insurance portable

- Expand Health Savings Accounts

- Aggressively reform medical liability

- Aggressively slow Medicare and Medicaid spending growth, and use the savings for long-term deficit reduction

Don�t:

- Raise taxes

- Create a new government health entitlement

- Mandate the purchase of health insurance

- Have government set private premiums

- Create a government-run health plan option

- Have the government mandate benefits

- Expand Medicaid

Results:

- Lower premiums, higher wages

- Portable health insurance reduces “job lock”

- +5 million insured (net)

- 100 million people will pay lower taxes

- 30m with expensive health plans pay higher taxes

- No net tax increase overall

- Reduces short-term and long-term deficit

- Fair to small business employees & self-employed

- Incentives and individual decisions “bend the cost curve down”

- More individual control & responsibility for medical decisions

(photo credit: Burnett: CNBC, Dean: Wikipedia)

Watch me debate Governor Dean at 2 PM on CNBC

Former Governor Howard Dean and I will be guests on CNBC’s Street Signs this afternoon at 2 PM EDT, hosted by Erin Burnett. We will be discussing health care reform.

(photo credit: Burnett: CNBC, Dean: Wikipedia)

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission

Yesterday Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) appointed me to be a member of a new Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. I thank the Leader for the appointment, and will do my best to contribute thoughtful, open-minded, rigorous and responsible analysis and inquiry.

The Commission was created by Public Law 111-21, the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009, signed into law by President Obama on May 20, 2009. The purpose of the Commission is “to examine the causes, domestic and global, of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.”

I am one of 10 members. Here is the full roster, along with the Congressional leader who appointed each:

- (Chairman) Phil Angelides (Pelosi, chosen as Chair by Pelosi and Reid

- (Vice Chairman) Former Rep. Bill Thomas (Boehner, chosen as Vice-Chair by Boehner and McConnell)

- Brooksley Born (Pelosi)

- Byron Georgiou (Reid)

- Former Senator Bob Graham (D-FL) (Reid)

- me: Keith Hennessey (McConnell)

- Doug Holtz-Eakin (McConnell)

- Heather Murren (Reid)

- John Thompson (Pelosi)

- Peter Wallison (Boehner)

The statute creating the Commission requires us to “submit on December 15, 2010 to the President and to the Congress a report containing the findings and conclusions of the Commission on the causes of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.”

Some in the press are comparing this commission to the 9-11 Commission and to the Pecora Commission during the Great Depression. I think it’s too early to draw any definitive parallels.

I expect to write on KeithHennessey.com about my work on the Commission over the next seventeen months. Those of you familiar with my blog should have a fairly good idea of what to expect.

For those who are new to this site, I also have a free mailing list tied to the blog. If you would like to track my work on the Commission, you can subscribe to the mailing list or the RSS feed, and/or visit the blog. I write about a wide range of economic policies, not just financial policies. So don’t be surprised when you see substance from me on anything from taxes and trade, to health care and social security, to energy and climate change, or to the broader macroeconomic and policy picture.

To get things rolling:

- I have assembled some background on the Commission. Most of this substance is in today’s papers, but I thought I’d lay out my structural description here for reference.

- I am seeking input. Please help educate me so I can do a good job on the Commission. Please use the contact information I provide below.

- I am building a preliminary reading list for myself and anyone else who might care. I will post a first draft when it’s solid.

- On the top horizontal menu bar you will see a list of subject categories. The “financial” category contains past posts and some of my White House work that is relevant, and it will contain all future posts related to my work on the Commission.

I anticipate that my work on the Commission will become a significant portion of the future content of this blog, so stay tuned. I enjoy solving problems, especially when they’re hard and important. I also like to explain complex and important stuff in a way that non-experts can understand. I hope you will let me try to do that as I gain new and different perspectives on the financial and economic crisis in the United States.

For today, though, let’s get some mechanics out of the way.

Background on the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission was created by Public Law 111-21 (formerly known as S. 386), signed into law by President Obama May 20, 2009.

(I will abbreviate the Commission as FCIC.)

P.L. 111-21 is the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009, a bill strengthening enforcement of various types of financial fraud crimes. The Commission was created by a bipartisan Senate amendment to that bill, offered by Senator Johnny Isakson (R-GA) and Senator Kent Conrad (D-ND). The amendment was adopted 92-4, a good sign of initial bipartisan support. The four Senators opposing were Bunning (R-KY), Grassley (R-IA), Kyl (R-AZ), and McCain (R-AZ).

Here is the text of Section 5 of the law creating the Commission. I will walk through it. This mechanical stuff may seem boring, but it’s important. If you find errors in the following description, I welcome corrections.

Establishment

The Commission is technically in the Legislative Branch. The purpose is “to examine the causes, domestic and global, of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.” We are required to issue a report to the President and to the Congress on December 15, 2010.

Membership

There are ten members, appointed by the “bicam

The Commission Members cannot be Members of Congress, nor government employees of any sort. They are supposed to be “prominent United States citizens with national recognition and significant depth of experience in such fields as banking, regulation of markets, taxation, finance, economics, consumer protection, and housing.”

Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid jointly chose the Chairman, Phil Angelides. Leaders Boehner and McConnell jointly chose the Vice Chairman, Bill Thomas.

Functions of the Commission

The Commission has five functions:

- “To examine the causes of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.” A list of 22 specific items for us to review follows.

- “To examine the causes of the collapse of each major financial institution that failed (including institutions that were acquired to prevent their failure) or was likely to have failed if not for the receipt of exceptional Government assistance from the Secretary of the Treasury during the period beginning in August 2007 through April 2009.”

- To submit a report to the President and the Congress on December 15, 2010. That report should contain our findings and conclusions on the causes of the crisis. The Chairman can also include reports or specific findings on any particular financial institution that failed.

- To refer to the Attorney General and State AG’s as appropriate “any person that the Commission finds may have violated the laws of the United States in relation to such crisis”

- “To build upon the work of other entities, and avoid unnecessary duplication, by reviewing the record of” a host of existing bodies, including the House Financial Services and Senate Banking Committees, the GAO, and just about anybody else in government.

Here is the long list of 22 specific causes the Commission must investigate under function (1) above:

- fraud and abuse in the financial sector, including fraud and abuse towards consumers in the mortgage sector;

- Federal and State financial regulators, including the extent to which they enforced, or failed to enforce statutory, regulatory, or supervisory requirements;

- the global imbalance of savings, international capital flows, and fiscal imbalances of various governments;

- monetary policy and the availability and terms of credit;

- accounting practices, including, mark-to-market and fair value rules, and treatment of off-balance sheet vehicles;

- tax treatment of financial products and investments;

- capital requirements and regulations on leverage and liquidity, including the capital structures of regulated and non-regulated financial entities;

- credit rating agencies in the financial system, including, reliance on credit ratings by financial institutions and Federal financial regulators, the use of credit ratings in financial regulation, and the use of credit ratings in the securitization markets;

- lending practices and securitization, including the originate-to-distribute model for extending credit and transferring risk;

- affiliations between insured depository institutions and securities, insurance, and other types of nonbanking companies;

- the concept that certain institutions are `too-big-to-fail’ and its impact on market expectations;

- corporate governance, including the impact of company conversions from partnerships to corporations;

- compensation structures;

- changes in compensation for employees of financial companies, as compared to compensation for others with similar skill sets in the labor market;

- the legal and regulatory structure of the United States housing market;

- derivatives and unregulated financial products and practices, including credit default swaps;

- short-selling;

- financial institution reliance on numerical models, including risk models and credit ratings;

- the legal and regulatory structure governing financial institutions, including the extent to which the structure creates the opportunity for financial institutions to engage in regulatory arbitrage;

- the legal and regulatory structure governing investor and mortgagor protection;

- financial institutions and government-sponsored enterprises; and

- the quality of due diligence undertaken by financial institutions.

Major Powers of the Commission

- The Commission may hold hearings, take testimony, receive evidence, and administer oaths.

- The Commission can require “the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of books, records, correspondence, memoranda, papers, and documents.” If necessary, the Commission can issue subpoenas to achieve this goal.

- Finally, the Commission can get “any information related to any inquiry of the Commission from any part of the government.”

I am seeking input

In an attempt to become a well-informed member of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, I am seeking input. Please help educate me.

I am building a reading list for myself. I will post a first draft when it’s solid.

From whom I most need help

I will take help and input from anyone willing to provide it. There are some channels that I know can help me a lot.

In particular, I would value highly:

- original writing by individuals with substantive expertise in any of the areas covered by the commission; and

- information and insight from those who were involved, from any perspective.

I need the most help from those with direct experience working in the financial sector, especially over the last several years. I will take it from any level of the corporate org chart — those in the “C” suites, and the analysts, associates, and traders who work on the front lines.

I also could use help from the academic community. Please send me your papers or links to them.

I could use help and input from members of the press who have been covering this crisis.

I would greatly appreciate input from those based outside the U.S. We are supposed to “to examine the causes, domestic and global, of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.” Distance can give perspective, and a comparison with other nations can be enormously instructive.

How to provide input

If you have something you think I should see, please email it to me at: kbh [dot] fcic [at] gmail [dot] com

As part of your email, please include your name, profession, contact information, and relevant professional background. I will take anonymous input, but may weight it less heavily, depending on the apparent reason for the anonymity.

Shorter is better. If you send me a short email, I’ll read it. If it’s a 1-3 page memo, I’ll do my best to read it. If you send me a 100-page treatise, I expect I’ll skim it.

If your email includes the phrase “secret global conspiracy” or is in all caps, or contains more than three curses, you should assume that I’ll skip it.

Please assume that your input is basically one-way. In almost all cases, don’t expect a private email dialogue with me based on your input. You should anticipate that most of my feedback will come publicly through this blog. This is more efficient and transparent.

This is not a substitute for formal input to the commission

I assume there will be a formal process for submitting input to the Commission. This is not that process.

In particular, the Commission is supposed to refer to the Attorney General of the United States, or to State AG’s as appropriate, “any person that the Commission finds may have violated the laws of the United States in relation to such crisis.” Please provide any information you have with respect to this mission directly to the Commission, through official channels, and not directly to me through this channel.

This input channel is to help educate me to be a better member of the Commission, not to serve as a generic inbox for the commission, and especially not to serve as an inbox for accusations of criminal wrongdoing.

What we’re supposed to inquire about, learn, and figure out

I have a fairly strong knowledge base from my experience in the Bush White House from 2002 through 2009. There is more for me to learn, and I am directing my studies to match the formal mandate of the Commission. You can help me most by tailoring your input to fit some part of this mandate.

We are supposed to:

- “examine the causes of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States;” and

- “examine the causes of the collapse of each major financial institution that failed (including institutions that were acquired to prevent their failure) or was likely to have failed if not for the receipt of exceptional Government assistance from the Secretary of the Treasury during the period beginning in August 2007 through April 2009.”

In the future I may pose some specific questions where I need help and education. For now, if you want to provide input, please put yourself in my shoes. Help me achieve the above two goals, and in particular tell me into which of the 22 subject-matter buckets listed above your input falls.

A little bit about me

I imagine that with this post some readers are discovering this blog and mailing list for the first time. You can find my bio here. Here are a few facts salient to the FCIC:

- I worked in economic policy for more than 14 years. For more than six years I worked for President George W. Bush at the White House National Economic Council.

- In 2008 and January of 2009 I was the Director of the National Economic Council, a position best known for its current occupant, Dr. Larry Summers. Dr. Summers has my old job.

- I am fairly certain this means I am the only member of the FCIC who worked in government during 2008. I hope this means I have an important perspective to contribute to the Commission.

- Since I launched this blog in late March I have posted many times on issues relevant to the Commission’s mandate. You can find all of them by tracking the financial categoryin this blog (bookmark the “financial” link in the horizontal menu bar right below my name). To get you started, here are posts that I think are the most relevant to the Commission’s work:

- Six month economic policy status update

- What happened to FREE markets in London?

- How much bailout money will taxpayers get back?

- Intro to TARP (a four-part series)

- Should bank stress test results be public?

- A series on the $700 B TARP constraint

- Bonuses and the peril of Congressional hindsight

- While I don’t think it’s central to the financial crisis, the auto loans/bailouts are clearly a major element of our economic problems, and they largely fall within the timeframe of the Commission’s mandate. I coordinated the auto issue for President Bush, and have written a lot about it since then:

- Auto loans: a deadline looms

- Auto loans, part 2: options for the President

- Auto loans, part 3: the Bush approach

- Auto loans, part 4: Chrysler gets an ultimatum, GM gets a do-over

- Auto loans, part 5: The press forgot to ask about the cost to the taxpayer

- Should taxpayers subsidize Chrysler retiree pensions or health care?

- The Chrysler bankruptcy sale

- Mixed results on the Chrysler announcement

- Responding to Chrysler comments

- Understanding the President’s CAFE announcement

- Basic facts on the General Motors bankruptcy

- Understanding the General Motors bankruptcy

- Dr. Goolsbee gets it wrong on the auto loans

- Government Motors discussion on Fox News Sunday (continued)

- I had a semi-public economic policy mailing list when I worked for President Bush. I have posted on my blog most of the emails I sent to that list, the content of which was derived from my work in the White House. Here are some big ones that are relevant to the Commission’s work. You can find all of them in the financial category archive.

- Subprime mortgages (7 September 2007)

- Subprime mortgages (part 2) (13 September 2007)

- Address by President Bush on financial markets (24 September 2008)

- What caused this financial mess?

- Are banks hoarding taxpayer investments?

- President Bush’s speech on financial markets and the world economy (13 November 2008)

- The G-20 Summit in pictures (just for fun)

- What was accomplished at the G-20 Summit?

- If you search hard enough, you can probably find video or transcripts of some interviews I’ve done since early 2008. Here’s one from about a month ago on CNBC. I anticipate being on CNBC tomorrow at about 2 PM EDT with Erin Burnett.

Thanks for reading. If you’re new to this blog and mailing list, I hope you will subscribe and return.

(photo credit: All that’s left! by pfala)

The wrong health reform will hurt the economy

The president is correct that health care reform is essential to a strong economy. He accurately identifies the underlying problem as extraordinary growth in health spending, leading to slower wage growth, too many uninsured and unsustainable government spending. He is correct that reform needs to “bend the cost curve” downward to stop families, employers and governments from chasing their own tails. Unfortunately, the legislation being developed in Congress moves in the opposite direction.

After the vice president admitted the administration had misread the economy, the president said administration officials, instead, had incomplete information – but yet they would not have done anything different in the too-slow stimulus. We need to prevent a recurrence of the stimulus mistake on health care.

At a time of rising unemployment and extraordinary short-term economic weakness, these bills would hurt the U.S. economy. The economic damage they would cause outweighs the benefit of reducing the number of uninsured.

Does the House really want to raise taxes on eight million uninsured people?

The President has said he would not allow taxes to be raised on anyone with less than $250,000 of income.

Today for the first time we see the legislative language for and a summary of the health care reform bill that House Democrats intend to try to pass before the August recess. The following is based on an initial quick scan of the bill and studying a few key sections. I have been wondering how the drafters were going to solve the problem I am about to describe. As best I can tell, they didn’t solve it.

As expected, the House bill would mandate that individuals and families have or buy health insurance.

But what if they don’t buy it?

Then Section 401 kicks in. Any individual (or family) that does not have health insurance would have to pay a new tax, roughly equal to the smaller of 2.5% of your income or the cost of a health insurance plan.

I assume the bill authors would respond, “But why wouldn’t you want insurance? After all, we’re subsidizing it for everyone up to 400% of the poverty line.”

That is true. But if you’re a single person with income of $44,000 or higher, then you’re above 400% of the poverty line. You would not be subsidized, but would face the punitive tax if you didn’t get health insurance. This bill leaves an important gap between the subsidies and the cost of health insurance. CBO says that for about eight million people, that gap is too big to close, and they would get stuck paying higher taxes and still without health insurance.

Example 1:

Bob is single and earns $50K per year. He earns more than four times the federal poverty level, so he does not qualify for subsidies under the House bill.

Bob works for a five-person small business that does not provide him with health insurance. His $50K wage is average for this company, which therefore does not qualify for the new small business tax credits.

This company is small enough that they do not have to pay the IRS any fee for not providing Bob with health insurance. (See the table on page 184.)

With only $50K of income, Bob cannot afford to buy health insurance. Under the House bill, he would then have to pay about $1,150 per year in higher taxes to the government. That’s 2.5% of (his income minus a $3,650 personal exemption).

I went shopping for Bob on eHealthInsurance.com. He is 50 years old and a non-smoker, living where I do in Virginia. The cheapest bare bones policy he can get is $1,620 per year. Most plans are in the $3K – $5K range. That $470 difference between the tax and the cheapest premium is more than Bob can afford on a $50K pre-tax annual wage.

To summarize, under the House bill:

- Bob is a single 50-year old non-smoking small business employee who makes $50K per year before taxes and does not have health insurance.

- Bob cannot afford a $1,600 bare bones health insurance policy, much less a $3K — $5K policy.

- Bob would get no subsidies under this bill, and his employer would face no penalty for not providing him with health insurance.

- Bob would end up without health insurance and would have to pay $1,150 more in taxes.

Example 2:

Freddy and Kelsey are married with two kids. They earn $90K per year. They earn more than four times the federal poverty level, and therefore do not qualify for subsidies under the House bill.

Freddy and Kelsey own and run a small tourist shop in Orlando, Florida. They are the only two employees. Their wages exceed the amounts that would qualify them for small business tax credits under the House bill.

Because their business is so small, the House bill would impose no financial penalty for not complying with the employer mandate. Even if they did, the tax penalty would come out of their own bottom line, since the two of them are the business.

Freddy and Kelsey are both 40 years old. They have a 15-year old son and a 12-year old daughter. None of them smoke.

Shopping on eHealthInsurance, the cheapest plan I could find for them is a high-deductible PPO plan with a $6,000 annual deductible. That would cost them more than $3,800 per year. And it’s a bare-bones plan.

They can’t afford that. Maybe they are recovering from a hurricane, or dealing with the real estate collapse in Florida. They are also saving for their kids’ college, which is only a few years away. Even with $90K of income, money is tight for a family of four.

If they cannot afford the (at least) $3,800 in health insurance premiums, then the House bill would make them pay more than $2,050 in higher taxes.

To summarize, under the House bill:

- Freddy and Kelsey are a 40-year old couple with two kids. They own and run a small tourist shop in Orlando, Florida.

- They are the only employees, and earn a combined $90K per year.

- They cannot afford even an inexpensive health insurance plan, and so the House bill would make them pay $2,050 in higher taxes.

These two examples show the difficulty of making an individual mandate work. To get people to comply with the mandate, you have to impose a significant tax penalty on those who don’t comply. This will change the calculation for many who were previously uninsured – they will buy health insurance, because the delta between the cost of having insurance and the tax penalty cost of not having it has shrunk, so they might as well buy it.

The bigger this gap, the fewer people will switch. And for those who do not or cannot comply with the mandate, they end up in the worst of all worlds – uninsured and paying higher taxes.

From CBO’s new tables, it appears that about eight million U.S. citizens would fall into this category. I expect that very few of these people would have more than $250,000 of income, the no-tax-increase line defined by the President.

I expect the House Democrats will emphasize that their bill would result in 97 percent of U.S. citizens having coverage. Those other three percent, however, really get shafted, and that’s about eight million people.

If the President were to sign such a bill into law, I cannot figure out how his team could reconcile this consequence with his pledge not to raise taxes on the middle class.

But without the tax penalty, the mandate isn’t effective, and the number of resulting uninsured goes way up.

The House bill drafters have made a hard policy choice. It is important that Members of Congress and the public understand the benefits and the costs of the approach they have chosen.

Update

Thanks to a friend for pointing this out: We know the President understands this point. Here is then-Senator Obama in a debate with then-Senator Clinton on February 21, 2008, opposing her proposal for a universal individual mandate to purchase health insurance (emphasis added):

SENATOR OBAMA: Number one, understand that when Senator Clinton says a mandate, it’s not a mandate on government to provide health insurance, it’s a mandate on individuals to purchase it. And Senator Clinton is right; we have to find out what works.

Now, Massachusetts has a mandate right now. They have exempted 20 percent of the uninsured because they have concluded that that 20 percent can’t afford it.

In some cases, there are people who are paying fines and still can’t afford it, so now they’re worse off than they were. They don’t have health insurance and they’re paying a fine.

(APPLAUSE)

In order for you to force people to get health insurance, you’ve got to have a very harsh penalty, and Senator Clinton has said that we won’t go after their wages. Now, this is a substantive difference. But understand that both of us seek to get universal health care. I have a substantive difference with Senator Clinton on how to get there.

(photo credit: speaker.house.gov)

Responding to the President’s op-ed

I would like to respond to the President’s Washington Post op-ed, “Rebuilding Something Better.” All quotes in this post are from the President.

Nearly six months ago, my administration took office amid the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression.

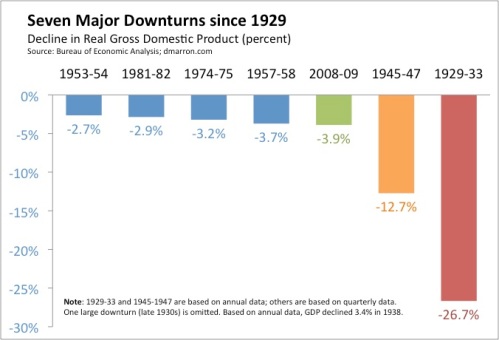

The President and his team use this language to lower the bar against which they are measured. The U.S. economy was quite unhealthy on January 20th, and it still is. Still, Donald Marron shows that, while the President’s statement is almost technically true, there is a big difference between “most severe … since the Great Depression” and “comparable to the Great Depression.” Here is Donald’s graph:

You can see that the recession of the past 19 months is not comparable to the Great Depression.

Nearly six months ago, my administration took office … and many feared that our financial system was on the verge of collapse.

Incorrect. In September-December of 2008, many feared that our financial system was on the verge of collapse. Large financial institutions were failing roughly every other week. By January 20th, we were pretty much out of the woods in avoiding a financial crash. Things were still bad and needed serious long-term repair, but that’s not the same as on the verge of collapse. Had our financial system been on the verge of collapse in January, we (the Bush team) would not have waited to draw down the last $350 B of TARP funding.

The swift and aggressive action we took in those first few months has helped pull our financial system and our economy back from the brink.

The President uses the past tense: “has helped.” Which actions, exactly, have had positive effects so far?

The Administration and the Fed deserve credit for the stress tests, which have encouraged banks to raise private capital. And they have continued the Bush Administration’s efforts to prevent particular too-big-to-fail financial institutions (AIG, Citi, Fannie & Freddie) from imploding.

They successfully followed the path (which President Bush laid in late December) to allow GM and Chrysler to enter and exit bankruptcy, although they did it in a much more heavy-handed way than we had hoped. President Bush’s and President Obama’s actions allowed these firms to avoid immediate liquidation, but it is too soon to call this effort a success.

That’s pretty much it so far:

- The stimulus has not yet had any measurable macroeconomic benefit, although it will, starting a few months from now.

- The much-hyped TARP “Financial Stability” program to buy risky assets (aka “the Public-Private Investment Partnership,” or PPIP) has been dialed back to a fraction of its originally proposed extent. The specifics were announced only last week.

- As of June 17th, CBO could find no evidence that any of the $50 billion allocated for foreclosure mitigation had been spent. (See footnote (d) on page 2.)

- The President’s announced small business loan program does not yet exist.

- The President’s budget would make our fiscal position much worse than current law, necessitating both higher taxes and more debt over the next decade. And, other than the stimulus and a huge appropriations bill, none of it has yet been enacted into law.

- Creeping Congressional and Administration protectionist actions are filling the gap left by Presidential inaction on the free trade agreements with Colombia, South Korea, and Panama.

Aside from the important and apparently successful stress tests for which the Administration and the Fed rightly deserve credit, the most successful and effective actions taken by the Obama Administration in its first six months were the continuation of the TARP capital purchase program and the extension of the auto loans. Both were initiated by President Bush.

I cannot see what else counts as as “swift and aggressive action” that “we

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was not expected to restore the economy to full health on its own but to provide the boost necessary to stop the free fall. So far, it has done that.

2.6 million fewer Americans are employed now than when the President took office, and the unemployment rate is 9.5% and climbing. Job loss in June was greater than in May. The good scenario is one in which we continue to lose jobs for “only” another six months. Please prove that the stimulus is working. To use the Administration’s misleading metric, how many jobs have been “saved or created” so far?

It was, from the start, a two-year program, and it will steadily save and create jobs as it ramps up over this summer and fall.

Uh-oh. Why are the verbs now in the future tense? And what happened to the specific and oft-repeated prediction of 3.5 million jobs by the end of next year? Those are important language changes, along with the implicit admission that the stimulus has not yet “ramped up.”

This did not have to be a two-year program. Congress could have front-loaded the stimulus had they instead given the cash directly to the American people, as they did on a bipartisan basis in early 2008. We would have saved much of it, paying off our mortgages, student loans, and credit cards (which would not be a bad thing). We would have spent the rest much more quickly than the federal and state government bureaucracies now stumbling through their usual corrupt, slow and inefficient processes. Instead the President handed the money and program design over to a Congress of his own party, who saw it as a big honey pot rather than as an exercise in macroeconomic fiscal policy. The President’s primary macroeconomic policy mistake was allowing Congress to pervert a rapid Keynesian stimulus into a slow-spending interest-based binge.

The President is correct that the stimulus will increase economic growth, mostly next year. That is too late, and later than it could have been had they done it right.

We must let [the stimulus] work the way it’s supposed to, with the understanding that in any recession, unemployment tends to recover more slowly than other measures of economic activity. … There are some who say we must wait to meet our greatest challenges. They favor an incremental approach or believe that doing nothing is somehow an answer.

So the President says we must wait for the stimulus to work, then attacks others who say we must wait “to meet our greatest challenges.”

Who says we must wait? Who favors an incremental approach to our greatest challenges, or believes that doing nothing is somehow an answer? These are straw men. I, for one, want to address these problems, but in a different way. In some cases the solutions being developed by Congress would do more harm than good. This does not need to be a choice between doing something and doing nothing, or between action and inaction. If the majority party would allow the minority to have votes on their policy proposals, this would instead be a debate among different models for reform.

Speaker Pelosi told the President’s team privately that we must not address Social Security reform. Our greatest immediate fiscal challenge is actually the rapid aging of the population, not health costs. This is notably absent from the President’s problem definition. We need to bend the health cost curve down and we need to address more immediate demographic pressures in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The Speaker says we must wait to address the Social Security challenge. She favors inaction.

To build that [stronger] foundation, we must lower the health-care costs that are driving us into debt, create the jobs of the future within our borders, give our workers the skills and training they need to compete for those jobs, and make the tough choices necessary to bring down our deficit in the long run.

Amen. But:

- The health reform bills being developed by a Democratic Congress would raise private and public health care costs and drive us even deeper into debt.

- Raising energy prices will hurt the economy, not help it. One could argue that the environmental benefit from reducing U.S. carbon emissions is worth it (I would not), but it is invalid to claim that higher energy prices will help our economy.

- CBO says the President’s budget would result in deficits averaging 5.2% over the next decade, and would increase debt held by the public from 52% of GDP this year to 80% by 2019. In the long run, we need to address immediate demographic pressures (which the Administration ignores) and change incentives to bend the long-term health cost curve down (which neither the President nor his Congressional allies have proposed).

- If we do not, then “make the tough choices necessary to bring down our deficit in the long run” just means “raise taxes.”

Already we’re making progress on health-care reform that controls costs while ensuring choice and quality, …

Maybe the President knows about a bill that has not yet been released. Every bill that is public so far would reduce incentives for individuals to consider the costs of the insurance they buy and the medical care they use, and would therefore increase health care costs. These bills bend the private and public sector health cost curves up, not down.

On “ensuring choice,” CBO estimates about 10 million people who under current law would be covered through an employer’s plan would under the Kennedy-Dodd bill not have access to that coverage because some employers would choose not to offer it. This breaks the President’s promise that “If you like your health plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan, period. No one will take it away, no matter what.”

Already we’re making progress on … energy legislation that will make clean energy the profitable kind of energy, leading to whole new industries and jobs that cannot be outsourced.

Yes, but at a cost to the economy as a whole. The House-passed bill would make clean energy profitable by raising the cost of carbon-based energy sources, which hurts economic growth. In addition, American manufacturers will have to pay higher energy prices that it appears their Chinese and Indian competitors will not. This hurts American firms and American workers.

I remain confused as to why the President believes he can claim that jobs in low-carbon energy technologies “cannot be outsourced.” Of course they can. The maintenance jobs cannot be outsourced, but design and manufacturing of clean energy technologies can be done anywhere in the world.

We must continue to clean up the wreckage of this recession, …

Lucky for us we have an economy that self-repairs over time. Economic growth will at some point return, with or without good policy. In the case of the financial sector, the capital purchase program and stress tests are accelerating the pace of recovery. In most all other cases, the President’s policies cannot be demonstrated to be helping. GDP continues to decline, and the anticipated good scenario is one in which job growth does not return until early next year. When you combine these uncomfortable facts with statements like “we misread the economy” and “we had incomplete information,” it is hard to see how the clean-up claim is justified.

After a rough ten days economically and politically, the President is trying to regain his footing and frame the week ahead.

The new jobs data has caused him to back off his specific commitment — there is no longer any mention of 3.5 million jobs by the end of next year. But the primary point of this op-ed is to signal a new message, captured most succinctly here:

[The stimulus] was expected to provide the boost necessary to stop the free fall. So far, it has done that. It was, from the start, a two-year program, and it will steadily save and create jobs as it ramps up over the summer and fall. We must let it work the way it’s supposed to, with the understanding that in any recession, unemployment tends to recover more slowly than other measures of economic activity.

The President’s new message is: No second stimulus. This one will work. Ride it out and be patient.

He’s right that it will help, eventually. If the July employment report due on August 7th returns us to the prior slow but steady recovery path, the President might only have to worry about 6-9 months of economic and political pain. But if the July report shows that the June report is a new downward trend, then policymakers will have a more serious problem to address.

The President’s op-ed is titled “Rebuilding Something Better.” Unfortunately I think there is a roadside construction sign reading “Expect lengthy delays.” Let us hope it doesn’t take too long for the rebuilding to work.

(photo credit: Sewer Construction at Commercial and Broadway I by roland)

How a bill really becomes a law: health care reform (part 1)

I recommend these excellent analyses and discussions of the health care reform debate:

- Kim Strassel’s Wall Street Journal column today, “Democrats Hoodwink the Health Lobby.” Kim is once again brilliant.

- David Brooks’ New York Times column today, “Whip Inflation Now.” I am honored that one of my favorite columnists would use my quote.

- Jim Capretta’s blog post, “Let the Unraveling Begin.”

I will attempt to supplement these writings by providing my tactical analysis of the ongoing legislative action on health care reform. As background, I was in the middle of every major health care legislative fight from 1995 through 2008. You can think of me as a retired player now serving as a color commentator with a telestrator.

In most of those debates I was part of a team helping analyze and manage legislative strategy, tactics, and process, in addition to my traditional policy role. My job was in part to help figure out how to achieve our policy goals in a complex system of conflicting legislative forces. Sometimes those policy goals were achieved by enacting a new law, and other times by blocking a bill or sustaining a veto.

I hope that some of my Washington friends with better information than I will continue to help me by calling or emailing with their insights with which I can improve this analysis. As usual I am long-winded, so I will break this up into multiple posts. I will begin with the basic legislative process.

The following analysis may frustrate you. It risks sounding superficial, Machiavellian, and as if it is not driven by policy. Please understand that I am here providing only one slice of a multi-layer analysis that also includes policy questions of enormous consequence, as well as a macro-partisan political layer. I have to tease these layers apart to have any chance of presenting it in a comprehensible fashion. The ultimate goal is always good policy (depending on your perspective). In pursuit of noble policy goals, the tactics can be calculating and brutal.

This may also seem somewhat abstract, as I am not going to discuss any policy here, only process and tactics. I hope it becomes clearer when I add substance in a future post.

My old boss Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (R-MS) once told me, “Others want to win the debate. You help me win the vote.” After all the important preliminaries, practical legislating ultimately becomes a question of procedural rules and how many votes you have on any given question.

Welcome to Part I of How a Bill Really Becomes a Law.

Health care reform legislative checklist

Here is the sequential checklist I would create if working for the current President, given his goal of enacting a new health care reform law. In reality I expect it would be the White House legislative affairs team that would do this, rather than the policy shop in which I used to work. Important open questions are in parentheses.

Step 1: Pass a bill out of the House in July.

Step 2: Get a bill out of (A) Senate Finance Committee, and a different bill out of (B) Senate HELP Committee. (Q: Timing on Senate Finance??)

Step 3: Senate Majority Leader Reid blends those bills (how?) with the aim of getting 60 votes on the Senate floor. He almost certainly does not use reconciliation. (Partisan, barely bipartisan, or broadly bipartisan?)

Step 4: Survive the Senate floor and pass a bill. Focus on (A) a handful of potentially killer amendments, and (B) getting 60 votes for cloture to shut down a filibuster.

Step 5A: Conference with the House. Manage House D disappointment.

Step 5B: Get 60 votes in the Senate for the conference report. Pass it in the House, too.

Step 6: Celebrate at White House bill signing.

The most difficult steps are 4B, getting 60 votes for cloture on Senate passage, and 5B, getting 60 votes for cloture and to pass the final conference report. Cloture is the vote to shut down a filibuster. The Senate floor amendment process in Step 4A also poses huge risks. The bill could unravel there.

Some suggested that Senate Majority Leader Reid would use the fast-track reconciliation process for health care reform so he would need only 51 votes for Senate passage. I continue to maintain my April view that this is highly unlikely, because reconciliation carries its own process costs. Major portions of the bill would likely drop out, allowing Leader Reid to pass only a Swiss cheese version of their desired reform.

Let us first examine cloture and final Senate passage (step 4B), then move down the checklist through conference. We will then move back up the list to earlier stages in the process.

Core concept: the marginal voter is in control on the Senate floor

On a simple one-dimensional and partisan issue, line up all 100 Senators on an imaginary policy line, with the most liberal on the left end and the most conservative on the right. Starting from the majority’s end (left in this case), count votes as you move right, drawing breakpoints after the 51st and 60th Senators. The Senators closest to the breakpoints and at the majority’s (left) edge are those with maximum leverage to modify a bill. So Leader Reid and the White House are trying to figure out how to get a bill that will be supported by liberals like Senators Rockefeller (WV), Mikulski (MD), Brown (OH), and Whitehouse (RI), and at the same time by moderates like Ben Nelson (NE) and Lincoln (AR).

You can see the advantage of reconciliation. If Leader Reid needs only 51 of 60 votes, he can produce a liberal bill that loses up to 9 moderate D votes, or a centrist bill that loses up to 9 liberal votes. If he needs 60 votes and his universe of possibles is only the 60 Democrats, he has no margin for error.

This is, of course, an oversimplification because legislation is never one-dimensional. In reality, if Leader Reid pursues a partisan path, each of 60 Democratic Senators is the marginal vote, and each can say, “I’d love to vote for this bill, but I need some changes.” Many of them will exert that leverage, some to fundamentally change the bill, and others to get a local hospital problem addressed or some other similarly trivial change.

You can also see the power of the moderate Republicans in a 60-vote situation. If Leader Reid thinks he can get 2-4 moderate Senate Rs to vote for cloture and final passage, then he has more flexibility to lose a slightly larger block of the votes on his left edge. Leaders make these decisions based on a variety of factors.

Leader Reid will have the ultimate responsibility for finding that sweet spot – where is the bill that just barely holds onto 60 votes on the Senate floor after a long and painful amendment process? In this case I think he is highly constrained by his thin margin and intense pressure from his left – he does not have a lot of room to maneuver. The public signals he is now sending are that he intends to pursue a partisan path, and not make concessions to pick up marginal Republican votes. This path keeps his liberals happy, but makes his job on the floor more difficult.

Forward into conference (maybe)

With 254 House Democrats in her caucus, Speaker Pelosi can lose 36 votes and still pass a bill without Republican votes. This gives her tremendous flexibility and dramatically weakens the leverage of individual or even groups of House Democrats. She wants but does not need those votes. This partly explains her tremendous power.

In contrast, Leader Reid is weak because he has no safety margin within his caucus of 60 Senate Democrats. In a conference negotiation with the House, this weakness becomes strength. The lead Senate conferees (probably Senators Baucus and Dodd, if the health care bill ever passes the Senate) would tell their House counterparts, “Of course we agree with you that we need a robust public option.” We actually like your more liberal and stronger version than the weak one we were able to get off the Senate floor. But we lost our moderates on that Senate floor vote, and they won’t vote for a final conference report if it has your version. The best version for which I can get 60 votes is the one that passed the Senate. So if you want a law, you need to recede to the Senate and take our provision.

They can repeat this argument on every issue, with varying levels of credibility. At times this argument is true. At other times, confirming the long-held suspicions of my many House friends, I have seen Senate chairmen in conference exaggerate their claims of Senate floor weakness in an attempt to gain leverage over their House counterpart. “My hands are tied.”

This is why the health care reform focus is on the Senate. If a health care bill passes the Senate (big if), the most likely scenario is that it gets 60 or 61 votes. If this happens, a conference report will almost certainly have to be quite close to that Senate-passed bill.

It also partly explains why key House players like House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Henry Waxman (CA) and Ways & Means Committee Chairman Charlie Rangel (NY) are shouting that they were not a part of the deals between Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (MT) and the hospitals, health insurers, and pharmaceutical industry. They are trying to maintain their relevance by suggesting that they too can blow up a deal in an eventual conference.

The marginal moderate Senate Democrat is significantly less liberal than the bulk of the House Democratic caucus, so if a final bill ever makes it to the President’s desk, it will look more like the Senate bill, which will be somewhat less liberal than what passes the House. I don’t want to exaggerate this — if a bill is produced, it will still be far left of center, to keep the bulk of Democrats onboard.

Backward into the Senate Finance Committee

Similarly, the Senate Finance Committee is more relevant than the Senate HELP Committee, because the Finance Committee negotiations more closely approximate the anticipated Senate floor negotiations for the 60th vote. With a 13 D – 10 R margin in Senate Finance, Chairman Baucus does not need any committee Republicans to pass (“report”) a bill out of his committee. He can even afford to lose one of his committee Democrats if necessary, and report out a bill 12-11. Why, then, is Chairman Baucus negotiating with his ranking Republican member, Senator Grassley (R-IA), as well as Finance Committee members Hatch (R-UT), Snowe (R-ME), and Finance Committee member and HELP Committee ranking Republican Enzi (R-WY)?

Chairman Baucus may genuinely want a bipartisan bill. In addition, he knows that if he secures the support of Grassley, Hatch, or Enzi, at least a few other Republicans will also vote aye, at least on the Senate floor. He and Leader Reid will then be working with a universe of more than 60 potential votes, and they will have some flexibility to lose liberal votes on the left edge of the Senate Democratic Caucus. A bill supported by Grassley/Hatch/Enzi is almost certain to become law, potentially at the expense (from the viewpoint of the left) of some substantive sacrifices.

Senators Grassley, Hatch, and Enzi each face a similar dynamic. If they think Senators Reid and Baucus are going to be able to get 60 votes without them and enact a law, then they may decide it is in their policy interest to negotiate to make that law better (or at least less worse). At the same time, Senators Grassley and Enzi are committee leaders on the Republican side, and they are being pulled away from a deal by most of their colleagues in the Senate Republican conference, who will almost certainly oppose any deal if it comes together (some on substance, and others for political reasons). This is a difficult balancing act, because as a ranking minority member on a committee, you represent the members of your party on that committee. If you are too far from most of them, you risk losing their confidence and their support on a wider range of issues.

Senator Hatch is the #2 Republican on Senate Finance and the presumptive successor to Senator Grassley as the ranking committee Republican, so he faces a similar dynamic. He is generally conservative but has cut bipartisan health deals in the past, most notably by being the key Republican (along with Senator John Chafee) who worked with Democratic Senators Kennedy and Rockefeller to create the children’s health insurance program, S-CHIP, in 1997.

Senator Snowe is the most moderate of the four Rs negotiating with Chairman Baucus. Getting her vote would give Chairman Baucus the political/press cover of a “bipartisan bill,” and the possibility to attract a couple more moderate Senate Rs. But while she is typically viewed as the most “gettable” of the bunch, she does not bring a lot of other Republicans with her, and thus does not significantly expand Leader Reid’s flexibility on the Senate floor later in the process. Senator Snowe is frequently the marginal vote on a wide range of issues and she is a savvy negotiator.

And while you can think of Chairman Baucus as the player with the most control at the moment, you can also imagine him as the rope in a tug of war. He is being pulled rightward (not much) by Grassley/Hatch/Enzi/Snowe, and at the same time he is being pulled leftward by his Leader and the majority of his Democratic colleagues. It was therefore unsurprising that after the Senate Democrats caucused for their weekly policy lunch last Tuesday, there were press reports that Leader Reid had ordered Chairman Baucus not to close a deal with the Republicans. Liberals were rebelling, or at least raising enough of a ruckus, so that their leader weighed in on their behalf to pull Chairman Baucus back to the left. This tug of war is ongoing.

Next steps

There are three obvious possible outcomes from the ongoing Senate Finance negotiations:

- Chairman Baucus cuts a deal with 1-4 Republicans.

- Chairman Baucus goes the partisan route and produces a bill with at least 12 of 13 D committee votes.

- He fails at both (1) and (2), and keeps delayed the committee markup.

At the moment, the winds blow against outcome (1), but those winds can shift quickly. Public indications of Leader Reid and liberals pulling Chairman Baucus leftward risk creating the impression among Republicans that, if Senators Grassley, Hatch, Enzi, or Snowe do accept a Baucus offer, they have been duped. This impression makes such a deal less likely. The outcome depends heavily on the substantive issues in dispute, which I will discuss in a future post.

Keep your eye on comments by Senators Baucus and Reid, as well as Senators Grassley, Hatch, Snowe, and Enzi. In particular, listen to what Chairman Baucus says about the timing of when the Senate Finance Committee will meet to consider (“mark up”) this bill. The more he hedges, the less success he is having in coming to a deal, either with Republicans or members on his own side of the committee.

In future posts I will try to explain the interactions underway with lobbyists and health care interest groups, and why the numbers make it so hard for Chairman Baucus to get a deal. Kim and Jim can get you started.

Giving thanks

Thanks to Karl Rove for his reference in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal column, and for the shout-out on Fox and Friends.

Thanks to Sean Hannity for the mention on his radio broadcast yesterday.

And thanks to David Brooks for the mention in his fantastic New York Times column today.