A “second stimulus?”

We are frequently asked whether there should be a “second stimulus” bill. Unfortunately, what is being considered on Capitol Hill is a very different animal from what we did earlier this year.

10-second macroeconomic review

GDP = Consumption + Investment + Government spending + Exports – Imports

= C + I + G + X – M

In January the President proposed, and in February Congress enacted, a bill that was short-term macroeconomic stimulus. We wanted that stimulus policy to be big, fast-acting, an efficient use of taxpayer dollars, and an effective stimulus to broad-based economic growth. We let taxpayers keep more of their wages, assuming that they would spend some of those refunds, thereby increasing consumption (C). We also temporarily cut taxes on business investment in an attempt to increase investment (I). The idea is that these two actions would quickly increase GDP. Millions of American workers and families and thousands of firms can react quickly to a change in their financial status.

This strategy appears to be working. We’ve got evidence from multiple sources suggesting that people are spending some of their stimulus checks, and that this is helping to support increased consumption. It’s harder to tell how much firms are taking advantage of the investment incentives, because it’s hard to measure that in real time.

In yesterday’s Wall Street Journal, Professor Martin Feldstein writes that the stimulus was a “flop.” Specifically, he argues that the recent GDP data show that the boost to consumer spending from the rebates was small relative to the overall size of the rebates. He estimates that $12 billion was spent out of a total of $78 billion in rebates paid out by the end of June. The core of his argument is that we didn’t get a lot of bang for the buck – only a small bump to GDP for a large loss of revenue for the government.

We disagree with this analysis. First, we think the stimulus bang is bigger than $12 B. Prof. Feldstein assumes that the growth in consumer outlays would have been flat had there been no stimulus. He then observes that consumer outlays actually grew by $12 billion more from Q1 to Q2 than they did in the prior quarter, and attributes that to the stimulus. Many observers think that, without the stimulus, consumer outlays would have grown more slowly in Q2 than in Q1. If this is the case (and we believe it is), then the effect of the stimulus is bigger than $12 billion.

In addition, we have felt only part of the bang so far. The stimulus enacted in February will have ongoing impacts in the upcoming months. Almost all the cash to consumers is out the door, but the resulting boost in consumer spending has not yet reached its full effect. We anticipate that the past stimulus law is continuing to increase GDP in the 3rd quarter, with a diminishing amount in the 4th quarter of this year. Monetary policy works with an even “longer lag” – the evidence suggests that when the Fed cuts interest rates, it takes about a year for half of the economic effect to take hold. So there’s more bang left in the remainder of this year from past actions on both the fiscal and monetary sides.

Allowing people to keep more of their money for one year is better than not doing so at all, so the loss of government revenue is actually a good thing if that money stays in the hands of the taxpayers who earned it, even if we can only get Congress to agree to do that for one year. We agree with Marty that the stimulus would be more effective if we had been able to enact a permanent tax cut, rather than a temporary one. Legislative realities forced it to be temporary. Permanent is better than temporary, and temporary is better than nothing.

On the second stimulus question, the following interchange from May 19th is instructive. Our deputy press secretary Scott Stanzel talked with a White House reporter at the “daily gaggle”:

Q: Scott, is the administration looking any more closely at a second economic stimulus package? The Commerce Secretary was on Late Edition over the weekend, and didn’t directly and definitively shoot that idea down.

MR. STANZEL: Well, what’s in the second stimulus package that you’re talking about?

Q: Well, just — I’m saying that many in Congress say we need a second economic stimulus package.

MR. STANZEL: Right, but what’s in that? That’s the thing. The idea of the second stimulus has become sort of this catch-all phrase for adding a lot of additional government spending, or doing things that Democratic leaders in Congress may have wanted to do previously, but are now — would want to sort of put under the umbrella of a stimulus package.

Before last Thursday, there was no second stimulus proposal. Now there’s a proposal from the Chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Senator Byrd (D-WV), but we have seen no indications that House or Senate Democratic leaders have signaled support for that proposal.

For more than two months we were asked to comment on something that did not exist. What does exist is pent-up demand in Congress to spend more money, and then to label that spending as a “second stimulus.” We anticipate that demand will only increase as we get closer to an election.

Congressional advocates for increased government spending this Fall have been arguing, in effect, that we should expand (G) in the equation above, and that doing so will increase economic growth.

But trying to stimulate short-term economic growth through increased government spending has a few problems:

- It’s slow. – Construction projects take years to plan and build. History shows that only about 27 cents of each dollar is spent in the first year.

- It’s often funneled through States. – Infrastructure spending and increased federal funds for programs like Medicaid result in transfers from the Federal government to State governments. This transfer doesn’t actually increase GDP, it just shifts money from one level of government to another. It’s more like putting in motion 50 potential stimulus packages, each of uncertain efficacy and speed. Some States might try to spend the funds quickly. Others might shift money around and use the Federal dollars to pay down debt, or wait until their State legislature convenes next year to allocate the funds. There’s also a danger that providing States with aid during challenging economic times will encourage states to spend irresponsibly during boom years, counting on Federal bailouts when times are tough.

You can make other arguments for spending more taxpayer funds on roads and bridges, but it’s a highly inefficient tool to stimulate immediate economic growth. Many of the advocates for a so-called “second stimulus” know that spending taxpayer funds on roads and bridges is popular with voting constituents.

There’s an important philosophical difference between the first stimulus (which was overwhelmingly bipartisan) and current Congressional attempts to increase government spending. The first stimulus proposed by the President looked at the economy as a whole, and tried to design a package that would help spur growth across the entire economy. Ideas being bandied about for a so-called “second stimulus” tend instead to take a constituency-based approach: they try to identify who is hurting, or who is politically powerful, and funnel government funding to them. Advocates then claim that these funds will stimulate broad-based economic growth.

We think that the first stimulus was both more fair and more effective by providing taxpayer rebates to more than 100 million Americans and broad-based business investment incentives to thousands of firms. And we think that there’s more economic bang still left from those recently implemented policies.

In summary:

- We think the stimulus is working and increased Q2 consumption and GDP.

- The effects of the first stimulus are not yet complete. Most of the cash is out the door, but we think there will be increased consumption effects this quarter, and a diminishing amount in Q4.

- For many, “second stimulus” is code for “allow Congress to increase politically popular government spending shortly before Election Day, and call it macroeconomic stimulus.”

- Increased government spending is slow and ineffective macroeconomic stimulus.

Thanks to Donald Marron, the newest Member of the Council of Economic Advisers, and to the CEA team for their help with his note.

USA Today op-ed: Keep taxes low

USA Today editorializes today against making the tax cuts permanent, and includes an opposing view from me.

I’ll include both here. I’ve learned that he who writes the opposing view is at a disadvantage, in that they get to see what I wrote, but not the reverse. I thought I had anticipated their attacks, but I only got one of them.

Here’s the USA Today editorial:

Our view on fiscal responsibility: Dr. Bush’s economic cures begin and end with tax cuts

Extension will drive up the deficit, won’t heal nation’s financial woes.

President Bush responded to Friday’s barrage of bad economic news – oil prices and unemployment soaring, the dollar and Dow sinking – with yet another call for extending his tax cuts. “In this period of economic uncertainty, the last thing Americans need is a massive tax increase – so Congress needs to send a clear message that the tax relief that we passed will be made permanent,” Bush said.

This little act of political theater isn’t just misguided. It’s also destructive. For one thing, Americans struggling to buy gasoline and pay next month’s mortgage are unlikely to be focused on tax cuts that might or might not expire in 2011. For another, these cuts – absent matching reductions in spending that Bush has never proposed – were irresponsible when enacted during Bush’s first term, and they are even more irresponsible now that the resulting deficits have added to the nation’s mountainous debt.

Despite inheriting a budget surplus, Bush has not presented a single balanced budget during his presidency, which coincided with the top earning years of the baby boom generation, a time when the government should have been preparing for the coming fiscal tsunami of the boomers’ retirement.

The fact that these tax cuts – which include reductions in marginal rates, repeal of the estate tax and a 15% rate on dividends and capital gains – are set to expire over the next several years reflects qualms that even a compliant Congress had when they were passed. The members who voted for them knew that they could not make them permanent without making a mockery of the budgetary rules. What’s more, they saw the boomers’ retirement approaching.

The situation has been compounded by the spree of spending and borrowing that followed these tax cuts. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the creation of a Medicare drug benefit and other initiatives have ballooned the national debt from $5.7 trillion in June 2001, when the first tax cuts were enacted, to $9.4 trillion today. That’s $3.7 trillion in new debt just as Medicare and Social Security are reaching crisis proportions.

It is easy, of course, for Bush to call for the permanent extension of these tax cuts. He won’t be around to deal with the consequences. Democrat Barack Obama or Republican John McCain will be, yet neither presidential candidate looks to be a model of fiscal prudence. Obama has called for rolling back the Bush cuts for wealthy taxpayers but proposes a bevy of new spending programs. McCain, meanwhile, voted against the 2001 cuts but now supports extending them without suggesting credible, offsetting reductions in spending.

At least McCain’s top domestic adviser, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, appears to recognize that there’s more to economic policy than cutting taxes. “Sadly,” he told Bloomberg Television on Friday, “it seems that is all President Bush understood in the economy.”

In opposing the extension of all these tax cuts, we do not mean to suggest that this nation can rely solely on tax hikes to bring the budget into control. Overspending is a bigger problem than undertaxation.

But the Bush tax cuts have aggravated the nation’s fiscal problems. And, to be realistic and blunt, if the country is to avoid a financial crisis much bigger than today’s appears to be, it will need both painful curbs in benefit programs and hikes in taxes.

This is not a particularly pleasant message, particularly in a presidential election year when the economy is faltering. But it is one that needs to be heard.

Here’s my piece.

Opposing view: Keep taxes low

Allowing Bush cuts to expire will slam families, strangle investment.

By Keith Hennessey

In 2001 and 2003, President Bush led a Republican Congress in cutting tax rates and the marriage penalty, increasing the child credit, eliminating the death tax, and reducing capital gains and dividend taxes. Without action by this Democratic Congress, those laws will expire in January 2011, and Americans will face the largest tax increase in history. Congress should make the tax relief permanent.

If Congress fails to act, a typical family of four earning $50,000 a year will pay $2,100 more in taxes. The marriage penalty will return in full force, and the death tax will return to life. Expensive gasoline is painful; imagine if your family also had to pay $2,100 more in taxes.

Raising taxes on work leads to less work. Americans will have less incentive to enter the workforce, work and earn more, and invest in education.

When you hear that we should raise taxes on the rich, remember that most small businesses pay taxes as individuals. Raising the top tax rate will harm these small business owners, from restaurants and dry cleaners to shopkeepers and repairmen.

Raising taxes on capital gains and dividends will strangle business investment.

If Congress instead keeps taxes low and cuts spending, firms will invest more, productivity and wages will rise, and our economy will grow.

When you hear that dividends and capital gains relief helps only fat-cat investors, remember that half of American households are invested in the market, including seniors living on dividend and pension income, and families invested in prepaid college tuition plans.

If America raises taxes on capital, that capital and the better jobs created by it will go elsewhere.

Some say we can’t afford more tax cuts. It is important to remember that our deficit challenge is a long-term problem driven by future increases in Social Security and health care spending. Washington should cut its spending so American families don’t have to cut theirs.

Future tax increases will impede further economic growth if the Democratic Congress stalls. American workers, consumers and entrepreneurs are doing their part to keep our economy growing. It’s time for members of Congress to do theirs.

Keith Hennessey is assistant to the president for economic policy and director of the National Economic Council.

The wrong way to address climate change

The Senate is now debating a climate change bill, typically referred to as the “Lieberman-Warner” bill, referring to Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-CT) and Sen. John Warner (R-VA). Technically, we think they’ll end up considering a slightly different version of that bill, offered by the Chair of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-CA). Since we’re fairly certain the Senate will actually be working off the Boxer language, I’ll refer to that.

Here is our Statement of Administration Policy (SAP) on this bill. It’s four pages, but a very easy read. If you’re at all interested in climate change policy, I highly recommend you read the whole thing.

Here’s the bottom line from the SAP:

For these and other reasons stated below, the President would veto this bill.

Before I dive into the problems with what this bill does, it’s important to understand what it doesn’t do. The Boxer amendment would not fix the problems with current law and climate change. Here’s what the President said about this on April 16th in the Rose Garden:

As we approach this challenge, we face a growing problem here at home. Some courts are taking laws written more than 30 years ago — to primarily address local and regional environmental effects — and applying them to global climate change. The Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act were never meant to regulate global climate. For example, under a Supreme Court decision last year, the Clean Air Act could be applied to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles. This would automatically trigger regulation under the Clean Air Act of greenhouse gases all across our economy — leading to what Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman John Dingell last week called, “a glorious mess.”

If these laws are stretched beyond their original intent, they could override the programs Congress just adopted, and force the government to regulate more than just power plant emissions. They could also force the government to regulate smaller users and producers of energy — from schools and stores to hospitals and apartment buildings. This would make the federal government act like a local planning and zoning board, have crippling effects on our entire economy.

Decisions with such far-reaching impact should not be left to unelected regulators and judges. Such decisions should be opened — debated openly; such decisions should be made by the elected representatives of the people they affect. The American people deserve an honest assessment of the costs, benefits and feasibility of any proposed solution.

The Boxer amendment does nothing to fix this problem.

The President thinks there is a right way and a wrong way to address climate change. This bill falls squarely in the “wrong way” category. It’s costly, bureaucratically dangerous, internationally counterproductive, and environmentally ineffective.

Costly

The SAP addresses costs on an individual and economy-wide level. It also describes the enormous expansion of government that this bill would entail. The following numbers come from two analyses: one done by the Environmental Protection Agency, and another by the Energy Information Administration at the Department of Energy.

At an individual level:

- The bill would increase gasoline prices 53 cents /gallon in 2030, and $1.40/gallon in 2050. (The effects of climate change policies are typically measured many years in the future, since the changes build up over time).

- It would increase electricity prices 44% in 2030, and 26% in 2050.

- It would reduce a typical household’s purchases by nearly $1400 in 2030, and by as much as $4400 in 2050.

At an economy-wide level:

- The bill could reduce U.S. GDP by as much as seven percent in 2050.

- It could reduce U.S. manufacturing output by almost 10% in 2030, before even half of the bill’s required emissions reductions have taken effect.

- EPA estimates the bill would impose $10 trillion of costs on the U.S. private sector through 2050. These costs would be passed through to you, the consumer, through the higher fuel and power costs described above. This would make the Boxer bill by far the most expensive regulatory bill in our Nation’s history.

And for the federal government:

- The bill would increase revenues by $6.2 trillion through 2050. That’s “trillion” with a “T.” It does this by creating “auction allowances,” and then auctioning those allowances to those who produce power. The vast majority of these higher costs will be passed through to you in the form of higher energy costs, producing the gasoline and power price increases described above.

- It would also give a bunch of these allowances away to States, foreign governments, and private entities. Our experts estimate the value of these allowances given away to be about $3.2 trillion. Again, that’s with a T. That’s a big giveaway. Strike that. It’s an enormous an unprecedented giveaway.

- The bill would increase federal mandatory (think “entitlement”) spending by $2.6 trillion through 2050, including $346 billion on new training and income support programs, and $750 billion in new foreign aid. This spending would be on autopilot, and not automatically subject to annual review as “discretionary” appropriated programs are.

Bureaucratically dangerous

The bill creates a staggering number of funds, commissions, and programs to oversee the market and provide “transition relief,” giving an unprecedented amount of control over the U.S. economy to unelected bureaucrats.

Two of the most powerful new bureaucracies are the Carbon Market Efficiency Board and the International Climate Change Commission. The Carbon Market Efficiency Board would oversee and regulate the new carbon trading markets, and would use “Emergency Off Ramps” and supplemental auctions to affect the supply of emission allowances if they believe the price is too high, allowing the emissions “market” to be subject to the whims of appointed bureaucrats (and the interest groups that lobby them). The International Climate Change Commission would dictate to importers which countries they can import from, and force importers to submit emission allowances (priced by the Commission) for each category of goods they import from each source country. The Commission would also auction off a separate pool of international allowances, the proceeds of which would be spent on a new State Department program established to mitigate the negative impacts of global climate change on disadvantaged communities in other countries.

These two new government organizations would have unprecedented and terrifying power to influence the growth rate of the U.S. economy, the composition of the economy, and our trading relations with other nations. The old Interstate Commerce Commission, which regulated railroads for more than a century, pales in comparison.

Internationally counterproductive

Last year the President launched an international effort that we call the “Major Economies” process. The Major Economies process is premised on the thought that if you want to have a measurable effect on the global climate, then all of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases need to work together. A solution doesn’t work if the emissions of the big developing nations (like China and India) keep growing unconstrained, while those of the big developed nations (like the U.S.) are limited.

The President’s lead negotiators on the major economies process, Dan Price and Jim Connaughton, have been working with their counterparts from the 16 other largest economies in the world. They’re trying to reach agreement this summer on a “leaders’ declaration” that would serve as an input into the broader U.N. discussion with 180+ countries. In this declaration, we are seeking agreement on a long-term emissions reduction goal, and on the need for all major economies to do their part.

The Major Economies process is an attempt at international cooperation with 16 other big countries. The Boxer amendment would mess this effort up at least in four ways:

- It would unilaterally impose large costs on the U.S. by limiting our emissions, whether or not other major economies do the same. This is silly, for even though the U.S. is the world’s second largest producer of GHGs, and we’re about 20% of the world total now, our share will become smaller over time as the developing country emissions grow faster than ours. Why impose a big cost on ourselves when we don’t even know that others are committed to take actions to do their part? (This was the flaw in the Kyoto agreement in the late 90s.)

- If we were to limit our emissions and a big developing economy did not, then some U.S. factories would close and their firms would build new factories overseas. The emissions source would shift to this economy. So U.S. workers and the U.S. economy lose, and global emissions aren’t reduced. We call this “emissions leakage” and “economic leakage.”

- The Boxer Amendment would then impose an “import surcharge” on goods from countries that don’t limit their emissions. Think about this – if China doesn’t change their emissions, we make Chinese goods more expensive for Americans to buy. Sure, that hurts Chinese producers, which someone might believe would encourage the Chinese to cap their own emissions (we disagree). But it also hurts American consumers.

- Threatening import surcharges impairs our ability to get major developing nations onboard with a new agreement. It could also start a trade war.

There’s so much bad in this bill, that’s it hard to rank the problems. But the international consequences, and the possibility of provoking a trade war, are at or near the top of the list.

In contrast, in addition to the Major Economies process, the President has proposed to immediately eliminate all trade barriers on clean energy technologies. He has also proposed creating an international clean energy technology fund, and has pledged $2 billion on behalf of the U.S. if others will chip in as well. That’s the right way to address climate change internationally.

Environmentally ineffective

You would think that a bill which imposes such large costs on the U.S. economy would at least do a lot to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the future global temperature, and therefore the chance of severe global climate change.

Here are the numbers:

- Based on estimates from the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, an increase of 90 parts of CO2 per million parts of atmosphere (ppm) would, over many decades, increase the global temperature by about 1 degree Celsius (I’m oversimplifying.)

- The Boxer amendment would reduce the CO2 in the atmosphere by between 7 and 10 ppm by 2050, and by between 25 and 28 ppm by 2095. (EPA estimate)

The scientists tell me I can’t just divide 7 or 10 by 90 (it’s not linear), but the basic point still holds: the Boxer amendment would reduce future global temperatures by far, far less than one degree Celsius.

So the Boxer amendment would reduce annual U.S. GDP in 2050 by as much as 7%, and U.S. manufacturing output by about 10% in 2030, in exchange for provoking a trade war and lowering the global temperature by less than one degree.

That’s the wrong way to address climate change, and it’s part of the reason why the President would veto this bill.

Defense earmarks

Each year Congress considers the “defense authorization bill.” This bill gives the U.S. military its legal authorities.

The House passed this bill last Thursday. One provision in the bill would attempt to limit the President’s ability to ignore certain earmarks in the report language that accompanied the bill. This is an important moment in the debate on how to handle earmarks.

I want to focus on those earmarks which are not written into the text of the bill, but are instead included in the report that accompanies the bill. I’m going to delve into the mechanics of earmarking and the current legislative dispute, because the details matter a lot.

As a reminder, we define an “earmark” like this:

(T)he term “earmark” means funds provided by the Congress for projects, programs, or grants where the purported congressional direction (whether in statutory text, report language, or other communication) circumvents otherwise applicable merit-based or competitive allocation processes, or specifies the location or recipient, or otherwise curtails the ability of the executive branch to manage its statutory and constitutional responsibilities pertaining to the funds allocation process.

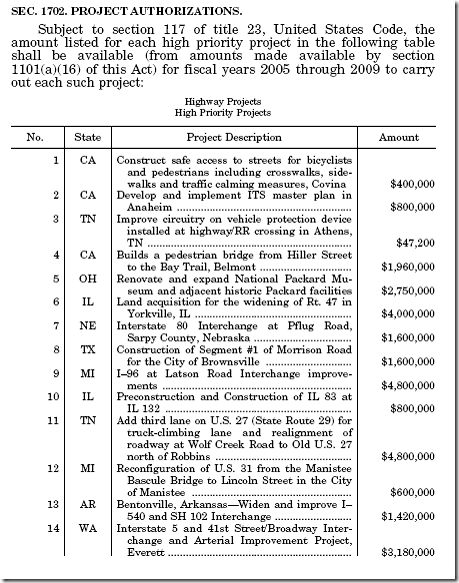

Here is a snapshot of part of a table in the highway law, enacted in 2005. This is an example of a earmark that was in the legislative language of the 2005 highway bill, and is now part of the law.

The full table of “high priority projects” in this highway bill is 197 pages long and contains 5,173 specific line item earmarks. Since they are part of the law, each one is a legal requirement – the Department of Transportation must fund each one.

Now let’s look at the committee report that accompanies the defense authorization bill. It, too, contains earmarks. Here’s one:

Niagara Air Reserve Base, New York

The committee believes that timely infrastructure improvements should be made at Niagara Air Reserve Base and should be provided priority in the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). Therefore, the committee urges the Secretary of the Air Force to accelerate projects, such as the programming to design and construct a small arms range at Niagara Air Reserve Base, New York, in the next FYDP.

Since it’s in report language and not legislative language, this earmark is not legally binding on the Executive Branch. Note the difference in form between a legislated earmark and one in report language:

- legislative earmark – “the amount listed for each high priority project in the following table shall be available …”

- report language earmark – “the committee urges the Secretary of the Air Force to …, such as … at Niagara Air Reserve Base, New York …”

In one case, the law requires the Department of Transportation to spend money in a certain way. In the other, the committee (which is only a subset of one House of Congress) “urges” the Secretary to spend money in a certain way.

As a practical matter, there’s little difference. Agencies typically try to follow these report language earmarks for various reasons, including the fear that if they don’t, the Member of Congress or the powerful Congressional staffer who originated the earmark will come back the next time around and cut their funding. As a result, while report language earmarks are not binding in any formal legal sense, they do affect agency behavior in the real world, and they distort agency spending decisions away from merit-based criteria.

The other important thing to understand about report language earmarks is that, if you work in Congress, they are relatively easy to get done. It’s pretty hard to change a spending bill as it moves through the legislative process, but it’s not that hard to get an earmark into a report. Reports are written by Congressional staff, and are never voted on or amended by Members.

Here is what the President said in the State of the Union address last year:

Next, there is the matter of earmarks. These special interest items are often slipped into bills at the last hour — when not even C-SPAN is watching. (Laughter.) In 2005 alone, the number of earmarks grew to over 13,000 and totaled nearly $18 billion. Even worse, over 90 percent of earmarks never make it to the floor of the House and Senate — they are dropped into committee reports that are not even part of the bill that arrives on my desk. You didn’t vote them into law. I didn’t sign them into law. Yet, they’re treated as if they have the force of law. The time has come to end this practice. So let us work together to reform the budget process, expose every earmark to the light of day and to a vote in Congress, and cut the number and cost of earmarks at least in half by the end of this session. (Applause.)

You’ll note that there are three components to the President’s 2007 earmark challenge:

- cut the number of earmarks in half;

- cut the cost of earmarks in half; and

- end the practice of earmarking in committee reports.

Here is what he said in the State of the Union address this year.

The people’s trust in their government is undermined by congressional earmarks — special interest projects that are often snuck in at the last minute, without discussion or debate. Last year, I asked you to voluntarily cut the number and cost of earmarks in half. I also asked you to stop slipping earmarks into committee reports that never even come to a vote. Unfortunately, neither goal was met. So this time, if you send me an appropriations bill that does not cut the number and cost of earmarks in half, I’ll send it back to you with my veto. (Applause.)

Then, on January 29th, the President signed an Executive Order (E.O. 13457), which included the following text:

(T)he head of each agency shall take all necessary steps to ensure that:

(i) agency decisions to commit, obligate, or expend funds for any earmark are based on the text of laws, and in particular, are not based on language in any report of a committee of Congress, joint explanatory statement of a committee of conference of the Congress, statement of managers concerning a bill in the Congress, or any other non-statutory statement or indication of views of the Congress, or a House, committee, Member, officer, or staff thereof;

The President therefore used this Executive Order to direct agencies to follow the law, but to ignore earmarks that are not in the law, those in report language. He instead told them to use “merit-based criteria” as the basis for determining how to spend. He has the right to do so, since report language is advisory and not legally binding.

Now let’s move to the new legislative issue. The defense authorization bill passed by the House last Friday contains a provision that tries to nullify this Executive Order, and to force the Executive Branch to follow earmarks in report language. Here’s the provision from the bill:

SEC. 1431. INAPPLICABILITY OF EXECUTIVE ORDER 13457.

Executive Order 13457, and any successor to that Executive Order, shall not apply to this Act or to the Joint Explanatory Statement submitted by the Committee of Conference for the conference report to accompany this Act or to H. Rept. XXX or S. Rept. XXX.

This is Constitutionally objectionable. Here are some questions raised by this language:

- How can a bill limit “any successor executive order,” when such does not yet exist?

- Does this section infringe on the President’s Constitutional authority to supervise the Executive Branch as he see fit?

- How can Congress prevent the President from directing agency heads to ignore something that is not in the law? (This one is my favorite.)

This section of the bill was debated on the House floor, but the House majority leadership used the Rules Committee to preclude consideration of an anti-earmark amendment by Rep. Flake (R-AZ). This amendment would have stricken section 1431 from the bill. Mr. Flake’s amendment would have been an excellent opportunity for Congress to take a significant procedural step toward reducing the number of earmarks, and toward forcing earmarks to be considered in the light of day on the House and Senate floors, rather than being hidden in committee reports.

Here is the relevant text on section 1431 from our Statement of Administration Policy (SAP). As you can see, this provision merited a veto threat.

If the final bill presented to the President contains any of the following provisions, the President’s senior advisors would recommend that he veto the bill.

…

Earmark Reform: The Administration strongly opposes the bill’s provisions to block the President’s recent Executive Order 13457, “Protecting American Taxpayers from Government Spending on Wasteful Earmarks.” This Executive Order made clear that future earmarks would be honored only if included in the text of legislation, building on the President’s pledge in his State of the Union address to veto FY 2009 spending bills that do not cut the number and cost of earmarks in half from FY 2008 levels. The President took this unprecedented action on earmarks to bring more transparency and accountability to the budget process – just as the American people expect and deserve. The President’s goal is to reform the earmarking culture that often slips earmarks into bills at the last minute, without discussion or debate – which contributes to the wasteful and excessive pork-barrel spending the Administration has seen in recent years. Section 1431 of the bill is also constitutionally objectionable in that it seeks to prohibit the President from supervising Executive Branch agencies as to discretionary matters and to have agencies implement informal preferences of Congressional committees that are not enacted into law.” Moreover, while Executive Order 13457’s objectives could still be accomplished by other means, this bill would cause confusion among agencies, inefficient use of resources, and unnecessary litigation potential.

The President is committed to “expos[ing] every earmark to the light of day and to a vote in Congress, and cut[ting] the number and cost of earmarks at least in half.” And he has issued veto threats to back that up. We’ll see whether Congress meets that standard.

The Farm Bill will be vetoed

We expect the House to vote on the Farm Bill conference report today. The President will veto this bill. Here is the President’s statement on the bill.

The final legislative language for the conference report was released Tuesday morning.

Hint: If you want to find the really bad stuff in a big bill, always start at the end of the bill’s Table of Contents.

A few of us have been debating the question “Which is the most important reason for the President’s veto of this bill?” Candidates include:

- Too much spending: The bill increases spending by almost $20 billion over the next ten years, at a time when net farm income is at an all-time high. Much of this additional spending is disguised by budget gimmicks that take advantage of formal scoring rules to hide real spending increases.

- New sugar program: The bill would make the government buy sugar for 2X the world price, store it, then resell it at about an 80% loss to the taxpayer. Sugar sells for about 11 cents/lb on the world market. The U.S. government would have to buy sugar for about 22 cents/lb, store it, and then auction off the excess to ethanol plants. We estimate that such an auction would net the government about 4 cents/lb. In addition, this new provision would require the government to guarantee that domestic sugar producers get 85 percent of the domestic sugar market.

- Subsidies for rich farmers: Farmers would be eligible for government subsidy payments if their incomes were as high as $1.5 million if married, and up to $750,000 if single. We had a big fight with Congress last year over whether families with income of 3 times the poverty level should receive taxpayer-subsidized health insurance. This bill would subsidize a married farming couple with income more than 107 times the poverty level (which is $14,000 for a couple). Put another way, such a couple would be in the top 0.2% of the income distribution. You would be subsidizing their business with your income taxes.

- Getting the best of both worlds: “Beneficial interest” is a provision of current law which allows you to lock in a government subsidy payment when the market price for your good is low, and then hold the actual good and sell it when the market price is high. You thus get the best of both worlds – subsidy payments as if crop prices were low, but profits from selling your good at a higher price. The President proposed a “pick-your-price” reform, in which you lock in the subsidy at the same time that you lock in the sale price, so you can’t play timing games. The conference report does not include this reform, and continues the practice of current law.

- Using food aid $ inefficiently: Under current law, U.S. food assistance for hungry people around the world must be spent purchasing U.S. crops. The President proposed to allow up to 25 percent of U.S. global food assistance to be spent purchasing food from local farmers (in the country where the people are starving). This allows U.S. dollars to be spent purchasing food, rather than paying transportation costs. It also encourages the development of farming infrastructure in these countries. Congress failed to include this forward-looking policy that will help save lives overseas. This means fewer starving people will get food, and these countries’ farming infrastructures will be less well developed.

- Earmarks:

- $500 M to purchase a 400,000 acre property from the Plum Creek Timber Company in Montana (Sec. 8401)

- $175 million to provide water to Nevada desert terminal lakes (Sec. 2807)

- $170 M for commercial and recreational members of some West Coast salmon fishing communities. (Sec. 12034) Note that the salmon fishing is a classic example of a “conference earmark.” It was in neither the House-passed nor the Senate-passed bill.

- Trail to Nowhere: Section 8303 “authorizes the Secretary [of Interior] to sell or exchange a few specific parcels in the Green Mountain National Forest designated on the map entitled ‘Proposed Bromley [Ski Resort] Land Sale or Exchange’ dated April 7, 2004. Funds from the sale of this land are to be used to relocate small portions of the Appalachian Trail or purchase additional land within the boundary of the Green Mountain National Forest.” Environmentally responsible drilling on federal lands in Alaska when gasoline is $3.72 per gallon is forbidden, but now skiing on Federal lands in Vermont will be OK. (A weekend lift ticket at Bromley is $63.) One person has labeled this provision the “Trail to Nowhere.”

- Permanent disaster assistance: Farmers can now buy crop insurance to protect themselves from low prices or crop failures. This bill also establishes a “permanent disaster assistance fund.” We fear that this would not replace emergency supplemental requests for more money when disaster strikes, but instead supplement such requests. There would be tremendous pressure to label even minor price or weather fluctuations as disasters, when there is sufficient funding available in this new pot.

We have, however, discovered a new problem with the bill. It has to do with trade, international labor standards, and Haiti.

There is a new Subtitle D to the conference report, titled “Trade Provisions.” It’s the last title in the bill. Section 15401 labels this as the “Haitian Hemispheric Opportunity through Partnership Encouragement Act of 2008.” This title provides enhanced trade preferences for textile imports from Haiti. This title was in neither the House-passed nor the Senate-passed bill. It’s about trade, not farming.

The bill effectively directs Haiti to establish a new program, called the TAICNAR Program: Technical Assistance Improvement and Compliance Needs Assessment and Remediation Program. This TAICNAR Program will be operated by the International Labor Organization (ILO), a U.N. agency that deals with labor issues. The TAICNAR, operated by the ILO, will write reports about whether Haiti is meeting its requirements on “core” internationally recognized labor rights, standards established by the ILO.

The bill then states that the President “shall consider” these reports as he makes his decision about whether a Haitian textile producer “has failed to comply with core labor standards and with the labor laws of Haiti that directly relate to and are consistent with core labor standards.” If he finds that the producer has failed to comply, he “shall withdraw, suspend, or limit” the trade preference for that producer.

This bill would subordinate the President’s decision-making on U.S. trade preferences to an international labor agency. It would mandate that he consider the ILO determinations on Haitian producers in granting or denying trade benefits.

We anticipate that, if a Haitian firm did not comply with an ILO standard, the new TAICNAR Program, run by the ILO, would report this to the President as a violation of its core labor standard, using the U.N./ILO criteria. If the President were to “consider” that report, and then decide not to withdraw, suspend, or limit the trade preference for that producer, the U.S. Government would be subject to endless petitions by mischief-makers, thereby forcing the President to undertake never-ending reviews to prove that he “considered” (and rejected) this U.N./ILO standard.

Q: Why should the President of the United States be required to consider determinations made by a U.N. agency as he makes a decision about a U.S. trade preference?

We’re still trying to understand the full ramifications of this provision (it’s 18 pages long). It appears that the International Labor Organization will effectively be telling the President what to do. At a minimum, it limits the President’s decision-making authority by requiring him to take certain factors into account in his decision, when the determinations underpinning those factors were not made by U.S. policymakers.

Statement by the President (13 May 2008)

If this bill makes it to my desk, I will veto it.

Food prices & food aid

The President spoke this afternoon about high food prices and food aid. If you’d like more detail, here’s our “fact sheet.” And if you really want to dive down deep, here is a transcript of a press briefing done by three senior administration officials after the announcement: OMB Deputy Director Steve McMillin, CEA Chairman Ed Lazear, and Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economic Affairs Dan Price.

I’d like to zoom out a bit and discuss how food prices interact with policy.

Let’s consider the following questions:

- How much are food prices increasing?

- Why are food prices increasing?

- What kind of effect is this having in the U.S., and what are we doing about it?

- What about overseas effects?

- What did the President announce today?

- Is the ethanol mandate contributing to the increase in food prices?

How much are food prices increasing?

Much of the increase in food prices worldwide is due to increases in grain prices. Since March of last year:

- wheat prices are up 146%

- soybean prices are up 71%

- corn prices are up 41%

- and rice prices are up 29%.

Why are food prices increasing?

- Increased demand in “emerging markets” (like China) accounts for about 18% of the rise in food prices. As people in poor countries get richer, they consume more meat. Since it takes a lot of grain to produce a little meat, as the proportion of meat in diets increases, the demand for grains increases.

- Rising energy costs have increased the cost of growing food, accounting for up to another 18% of the increase.

- Bad weather has harmed wheat harvests, especially in Australia, China, and Eastern Europe.

- Dollar depreciation accounts for a portion of the increase in U.S. food prices.

- Increased biofuel production has increased the demand for corn, but accounts for only 3% of the overall increase in global food prices.

What kind of effect is this having in the U.S., and what are we doing about it?

Food price inflation in the U.S. is up 4.5% over the year that ended in March, only slightly faster than the overall inflation rate of 4.0% (CPI). Certain staples are up by greater percentages: milk is up 23% over the same period, bread is up 16%, and eggs are up 35%.

Obviously, this inflation hurts, and family budgets get squeezed. On average, Americans spend about 14% of their total expenditures on food. But grain price increases don’t affect American food prices as much as they do food prices in developing countries, because grain prices are a relatively small portion of total food expenditures in the U.S. About half of all food dollars in the U.S. are spent dining out, and Americans eat more heavily processed food. Service costs (waiters, chefs) and food processing costs account for a large proportion of U.S. food spending.

There are two big federal programs that spend money on food. The U.S. government spends about $40 B a year on food stamps, helping about 28 million people this year. The food stamp program automatically adjusts to food price increases. In addition, the President’s budget proposes some changes to expand the food and vegetables component of food stamps, and to keep savings and combat pay from reducing eligibility for food stamps.

The Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program will spend about $6 B this year on about 8.6 million people. This year we have increased funding for WIC by more than 18%. And in mid-April we transferred about $150 M from a reserve to account for higher costs in WIC.

What about overseas effects?

Let’s look at Mozambique as an example of a developing country, and compare it to the U.S.

- Americans spend on average 14% of their total expenditures on food. In Mozambique, it’s 68% for those making under $1 a day.

- Food prices have increased 4.5% over the past year in the U.S., and 15.4% over the past year in Mozambique.

- The effect of one year of current food price inflation therefore means that an American has, on average, 0.5% less income to spend on other things. But in Mozambique, one year of current food price inflation squeezes out 10% of their income.

This is why international food experts talk about a food crisis – poor countries are acutely affected by grain price increases.

What did the President announce today?

To address this problem, two weeks ago my administration announced that about $200 million in emergency food aid would be made available through a program at the Agriculture Department called the Emerson Trust. But that’s just the beginning of our efforts. I think more needs to be done, and so today I am calling on Congress to provide an additional $770 million to support food aid and development programs. Together, this amounts to nearly $1 billion in new funds to bolster global food security. And with other food security assistance programs already in place, we’re now projecting to spend nearly — that we will spend nearly $5 billion in 2008 and 2009 to fight global hunger.

This funding will keep our existing emergency food aid programs robust. We have been the leader for providing food to those who are going without in the past, and we will continue to be the leader around the world. It will also allow us to fund agricultural development programs that help farmers in developing countries increase their productivity. And of course this will help reduce the number of people who need emergency food aid in the first place.

In addition, the President reiterated his call on Congress to support his proposal to allow U.S. dollars to be spent in poor countries to buy food from local farmers. This makes U.S. taxpayer dollars go farther to help more people, and it helps develop local agricultural infrastructure. (Teach a man to fish…)

Countries are moving in two different directions in response to higher food prices. Some are moving in the right direction: eliminating tariffs, permitting genetically modified foods, and increasing food assistance for their poor citizens. Others are moving in the wrong direction, restricting exports and imposing price controls on specific goods. These wrongheaded policies ultimately hurt the people who need the food, by restricting efficient trade and causing supply shortages.

Is the ethanol mandate contributing to the increase in food prices?

Right now it is not, because the price of oil is high, and other policies are supporting demand for ethanol. I’ll explain.

- Increased global demand for biofuels is increasing the price of food, but only a little. Our experts think about 3% of the global food price increase is a result of increased demand for biofuels.

- Two of three U.S. ethanol policies are contributing to that increase (the subsidy and the import tariff).

- But the mandate is not now big enough to affect ethanol demand, because oil prices, the ethanol subsidy, and the import tariff together produce more ethanol than the mandate requires.

- Given other ethanol policies and current market conditions, the ethanol mandate therefore is not affecting the price of corn or other food.

We have three domestic policies that affect ethanol supply and demand: the 51 cent /gallon tax credit (subsidy) for ethanol blended into fuel, the 54 cent /gallon ethanol import tariff, and the renewable fuel standard (RFS) mandate.

Our experts tell us that, given today’s high oil prices, the current RFS mandate is not “binding.” In other words, given the existence of the subsidy and the tariff, fuel blenders would be choosing to buy the same amount of ethanol as they are right now, even if the mandate did not exist. As evidence, the mandate in law is for 9B gallons of ethanol to be blended into fuel this year. But fuel blenders are blending about 9.15 B, more than this year’s mandate. When oil is in the $110-$120 range, and ethanol is subsidized 51 cents/gallon, you don’t need the government to tell you to buy ethanol, you do it because it’s cheaper than blending gasoline. If the subsidy weren’t in place, it would be a different story: the mandate probably would be binding and would be distorting fuel blending decisions. And the mandate could bind in the future, if the price of oil drops substantially, or in future years as the mandate increases. It could then affect the price of corn and other grains. But the President’s action last year, which was to propose an increased mandate, is not increasing the amount of ethanol used this year, and therefore is not now increasing fuel or food prices.

Our experts believe that increased use of corn to produce biofuels in the United States accounts for about 19% of the increase in the global price of corn. That’s 19% of the 41% increase in the price of corn over the last year, meaning that corn prices are about 8% higher in the U.S. as a result of increased domestic demand for ethanol. Corn is obviously only one of many grains, and grains are a subset of food, and food spending also includes food processing costs and the service costs of a waiter and cook if you go out to eat. When our experts combine all these factors, they conclude that increased worldwide use of biofuels has increased food prices by about 3%.

While increased demand for biofuels are responsible for some of the corn price increase, this does not mean that the increased RFS mandate is responsible for the 8% increase. Regular gasoline can contain up to 10% ethanol, and fuel blenders have to make a decision about how much ethanol to substitute for gasoline into a gallon of fuel (between zero and ten percent ethanol). There are two reasons why a blender might substitute more ethanol in place of gasoline:

- the RFS mandate in the law requires him to use more ethanol;

- or ethanol is less expensive than gasoline.

Let’s look at $116 oil (this morning’s opening price). That’s $116 for a barrel of West Texas Intermediate Crude (WTI), which is the really good stuff. Refiners use a mix of good and not so good stuff, so that on average the price they pay for oil run through their refinery is about $6 a barrel less than the WTI price. A barrel of oil contains 42 gallons, so crude oil costs 110 / 42 = $2.62/gallon. Add in refining, distribution, and marketing costs of roughly 50 cents/gallon to turn oil in to gasoline (it varies a lot), to get about $3.12 per gallon of gasoline, before taxes.

Now let’s turn to ethanol. Corn is currently trading for around $6/bushel. Estimates vary, but the break-even price for corn, which is the price per bushel a blender would be willing to pay to produce a gallon of ethanol and just break even, is currently above this price. This means that a fuel blender has an incentive to substitute ethanol for gasoline, no matter what the government tells him to do. It’s rational for this fuel blender to go all the way up to 10% ethanol in the fuel he sells, the maximum that U.S. vehicles can tolerate without modification.

So yes, increased ethanol usage has made corn about 8% more expensive over the past year. But it has not affected wheat prices, which have recorded the biggest grain price increase. And the higher U.S. ethanol prices right now are driven not by the higher renewable fuels government mandate, but instead by market forces that are looking for alternatives to $100+ oil. In contrast, the ethanol subsidy (51 cents per gallon) and the ethanol import tariff (54 cents per gallon) are subsidizing ethanol production relative to food production. Note that these two policies have been in effect since long before the President took office.

Conclusions

- World grain prices are up. Way up. Especially for wheat.

- U.S. food prices are up, but by a lot less, because raw inputs account for much less of our total spending on food.

- More meat-eating in developing countries, higher energy costs, bad weather, the $, and increased demand for biofuels all contribute to higher food prices.

- Poor countries are more severely affected by grain price increases than rich countries like the U.S.

- The President’s recent and new proposals total almost $1 B of new money to bolster food security. When combine with pre-existing plans, the U.S. will spend about $5 B this year and next to fight world hunger.

- Other nations can make the situation worse by raising protectionist barriers or imposing price controls. Either can cause a supply shortage.

- Increased demand for biofuels is contributing to the higher price of corn and soybeans, and that is in part attributable to subsidies in U.S. law. But the expanded ethanol mandate (“Renewable Fuel Standard”) has little to no effect on the current ethanol price, because the high world oil price creates a market incentive for fuel blenders to choose ethanol over gasoline.

Are taxes too low?

President Bush has signed into law 15 bills cutting taxes. The 2001 and 2003 tax laws were the biggies. Here’s a list.

This President has a well-established record as a tax cutter. Many of our critics argue that we cut taxes too much, and that we need to repeal some or all of the enacted tax relief.

These critics claim that taxes are now “too low.” They argue that we should repeal all the tax cuts, or at a minimum, allow them to expire in 2010 as they are scheduled to do under current law. Others argue we should allow some of the tax cuts to expire, those which they label as “for the rich.” I’m going to stay away from distributional arguments today, and instead focus on the aggregate level of taxation: how much in total is the Federal government taking from the private sector each year?

Are taxes too low now? Are they low by historical standards?

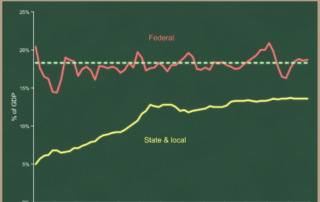

What can we learn from this graph?

- Federal revenues, measured as a share of the economy, have stayed basically flat since the end of World War II. They bounce around quite a bit, but the long-term trend is flat. Depending on when you start measuring, the average is a little above 18% of GDP. The green line is at 18.3% of GDP.

- State & local revenues climbed steadily from the end of WWII until about 1972, and have crept up since then.

- In 2009 under current law, the total federal + state + local tax take (on average) is 32.6%. That means governments are taking almost one-third of income and earnings from the people who produce them.

For comparison, the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts combined reduced the federal government’s take from the economy by about 1.2% of GDP.

Detour

Don’t forget that, while taxes have remained basically constant as a share of the economy since the end of World War II, this does not mean that government is the same size as it was 60 years ago. Government is much bigger, because our economy is much bigger.

Example:

- In 2009, current law taxes were projected to be 18.7% of the economy before the stimulus bill.

- In 1953, taxes were 18.7% of the economy.

- But the 2009 economy is more than 4X as large as the 1953 economy, so the government is more than 4X bigger in inflation-adjusted terms.

A flat share of the economy means that government gets bigger each year. Indeed, real revenues are more than 5% higher this year than they were in 2000, even though the share is a bit smaller.

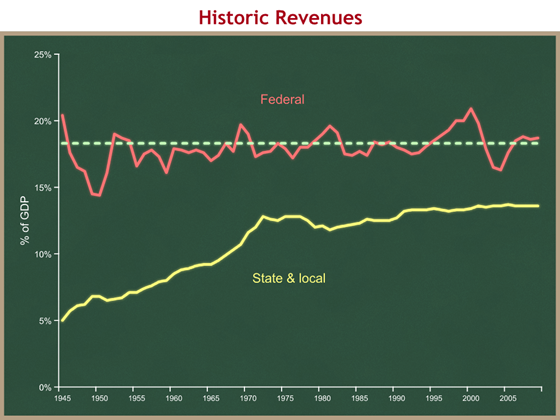

Now let’s review recent history. This President has signed 15 laws cutting taxes. The President gets criticized for cutting taxes “too much” (whatever that means). Given this record, you would expect taxes to be low compared to historic levels. Let’s take a look.

Amazing, no? Despite a tax-cutting President, taxes are now higher than the long-term historic average. Or, at least they were before the President signed the stimulus bill this past Wednesday.

Let’s dig into this graph a bit more. The big dip from 2001 to 2003 is because of three things:

- Revenues hit an all-time high of 20.9% of GDP in 2000. Some argue this was because of economic policies in the 1990s. A more plausible explanation is that revenues were inflated, along with many other financial indicators, by ephemeral tech bubble profits in the late 90’s. So we were coming down from an artificially high level.

- The economy entered a recession just as the President took office. Slower economic growth => less income => less taxes collected by the government.

- The President and the Congress cut taxes in the first half of 2001. This accounts for roughly 1.2 percentage points of the drop from 2001 to 2003 (much less than half).

Beginning in 2004 you can see the effect of the economic recovery on government revenues. Economic growth => more people working and higher wages and more wealth => revenues for the federal government grew from their low in 2004 (even with reductions in tax rates).

You can see that, before Wednesday’s new stimulus law, taxes were higher than their historic average. Now, they’re a bit lower. But there are a couple of other automatic forces in current law that push taxes up over time, and that will, as soon as next year, again push us above the historic average share of the economy. I’ll discuss those in the near future.

So if anyone suggests to you that:

- taxes are now “too low,” or

- we should repeal the enacted tax cuts, or

- we should raise taxes “on the rich” (or on some other politically unpopular constituency),

please remind them that taxes are now right about at their historic average, that they are projected to increase both in real terms and as a share of the economy, and that as soon as next year they will again be above their historic average share.

Taxes are not too low. Even after 15 tax cuts, the federal government is taking the same share of the economy as it has since the end of World War II. And taxes are scheduled to go up in the near future.

Enacting President Bush’s growth proposal

About three hours ago, the President signed into law H.R. 5140, The Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 , less than four weeks after he first proposed Congressional action.

We are enormously pleased with this rapid and bipartisan legislative success. The final bill passed the House 380-34, and the Senate 81-16. Here is a one-page summary of the bill, along with the text of the President’s remarks.

Details on rebate checks

A full description of the bill is below. The biggest part of the bill is the tax relief delivered through rebate checks.

- Qualifications: To qualify for a rebate, a person must:

- file a tax return for 2007 or 2008;

- have at least $3,000 of “earned income” or positive income tax liability in 2007 or 2008 (earned income is redefined to include Social Security benefits and Veterans’ benefits and compensation); and

- include a valid Social Security number on his tax return – those taxpayers with individual taxpayer identification numbers (ITINs) are not eligible for rebates (this is intended to prevent illegal aliens from participating).

- Individual Rebate: All qualifying taxpayers will receive a minimum of $300 ($600 in the case of a joint return), up to a maximum of $600 ($1,200 for joint returns) based on their income tax liability.

- Child Rebate: All individuals eligible for rebates also will receive $300 for each child living in their household that would qualify for the existing child tax credit (Note: children of illegal aliens would not be eligible, even if the children are U.S. citizens).

- Phase-Out: The amount of a taxpayer’s aggregate rebate (the individual rebate plus the child credit) will be reduced by 5 cents for every dollar of adjusted gross income (AGI) above $75,000 ($150,000 for joint returns). For example, the aggregate rebate of a joint return with $160,000 of AGI would be reduced by $500.

- U.S. Possessions (Puerto Rico, Guam, etc): The U.S. Treasury will reimburse territories for the cost of providing rebates to their residents on the same terms and conditions.

- Hold Harmless: Taxpayers who receive a rebate greater than merited based on 2008 tax info owe no money to the IRS; conversely those taxpayers who receive a rebate worth less than merited based on 2008 tax info are eligible for the difference when they file their taxes in the spring of 2009.

Because this happened so rapidly, rebate checks from the IRS will begin to be sent out the second week in May. Electronic deposits should begin the first week. It will take several weeks for all the checks to go out. For more details, go to the IRS website

For the overwhelming majority of taxpayers, these are rebates of taxes that will be paid in 2008, so I’m going to oversimplify slightly and just refer to them generically as ‘rebate checks.”

Scorecard: 8 1/2 out of 9

I’d like to return to the President’s proposal from three weeks ago today, and review how we did. I wrote then that the President said an effective growth package must be:

- Big enough to move the needle on a $14.5 trillion economy. The President proposed a package that’s 1% of GDP, or about 145 billion dollars in 2008.

The final bill is $168 B over two years, and our guess is that at least $152B will go out the door in 2008.

- Immediate. This means (i) Congress should pass legislation immediately. (ii) Policies with immediate macro effects are better than those with lagged effects.

The Congress passed the bill within three weeks of the President’s proposal, and the policies will have immediate macro effects (since they’re the ones the President proposed). - Based on tax relief. Individuals, families, and businesses will react quickly (and more effectively) if they are deciding how to spend more of their own money.

The entire package consists of tax relief, with two exceptions: some people will get checks that exceed their tax liability, and the bill increases the FHA & GSE conforming loan limits. But there is no spending through government bureaucracies, so we clearly met this test.

- Broad-based. Many were emphasizing “targeted.” In contrast, we think policies should be neutral and distort decisions as little as possible.

I think this one was a win-win. We got what we want — the tax relief is very broad-based, and not targeted at specific industries or sectors. At the same time, Speaker Pelosi was able to negotiate to “target” the income tax relief to low and middle-income people. While the President’s preference was to have income tax relief to those who pay income taxes, this was a principled compromise that was worth making.

- And temporary.

All provisions in the bill expire at the end of 2008.

The President said the bill must not:

- Raise taxes.

- Waste money on federal spending without an immediate positive effect on GDP growth.

Finally, we got a little more specific. Three weeks ago, the President said that a growth package must:

- Include tax incentives for American businesses to invest (especially small businesses).

- Include “direct and rapid income tax relief” to increase consumer spending.

How big is my rebate? What do I need to do?

The following calculations will work for virtually everyone reading this email. The only exceptions are for those with very very low taxable income. Rather than add 5X more complexity to the descriptions below, I’m going to leave those folks out of this quick-and-dirty algorithm.

If you’re married:

- Start with $600 for you + $600 for your spouse = $1200

- Add $300 per kid

- If your income last year is over $150,000, subtract ( 5% X (your income – $150,000) ) from the above subtotal

- You now have your rebate amount. If you end up with a number that’s less than zero, you’re out of luck – no rebate.

If you’re single:

- Start with $600

- Add $300 per kid

- If your income last year is over $75,000, subtract ( 5% X (your income – $75,000) ) from the above subtotal

- You now have your rebate amount. If you end up with a number that’s less than zero, you’re out of luck – no rebate.

You almost certainly don’t need to do anything to get a rebate check. As long as you file a tax return for 2007 income, you’re in the system. The IRS will do all the rest.

To close, here’s a Presidential quote from today’s signing ceremony. It stresses the importance of a flexible and dynamic market economy. We cannot prevent all bad things from happening. We can work to make sure the private sector maintains the flexibility and resiliency to adapt quickly when they do.

Over the past seven years, this system has absorbed shocks — recession, corporate scandals, terrorist attacks, global war. Yet the genius of our system is that it can absorb such shocks and emerge even stronger. In a dynamic market economy, there will always be times when we experience uncertainties and fluctuations. But so long as we pursue pro-growth policies that put our faith in the American people, our economy will prosper and it will continue to be the marvel of the world.