My BBC spot

Here is my brief interview on BBC 5 Live’s Wake up To Money. It aired at about 5:30 AM GMT, or 12:30 AM EDT.

My segment starts at 06:51, with me coming in at 08:30.

The BBC has amazing audio equipment in their DC bureau.

On air

I will be on BBC Radio 5 Live’s Wake Up to Money show at 5:30 AM GMT, 12:30 AM EST, talking about the G-20 summit. If you’re up, you can listen here.

I was on Fox News’ The Live Desk with Martha MacCallum this afternoon around 2:20 pm, talking about banks and taxpayer investments. Martha grilled me on whether the (current and former) Administration should discourage banks from paying Treasury back now, and whether the CEOs of the large banks should be fired.

I hope you will subscribe to the mailing list and/or RSS feeds in the right sidebar.

A quick guide to the G-20 summit

The President has arrived in London for the G-20 economic summit. I have different policy views than the President on some of these issues, but I will not criticize him while he is overseas. I will attempt to gently highlight a couple of substantive issues that concern me, but at the same time I want to send a clear signal that I support the American President and his team in negotiations with other states, even if I am not in the same place on some of the substance.

I wrote last November about the first G-20 Economic Summit, initiated and hosted by President Bush. You can see some neat behind-the-scenes photos of the gorgeous National Building Museum and read about the accomplishments of that summit. Last November the press tried to write the story “Lame duck President – not much accomplished.” That storyline was incorrect. Now we have a new American leader and one fundamental policy shift, but much of the agenda remains consistent.

There is a symbolically important change to watch for in the text of the leaders declaration, compared to that in the November text. I fear that the word “free” may be absent in the successor statement to this sentence from the November leaders declaration:

12. We recognize that these reforms will only be successful if grounded in a commitment to free market principles, including the rule of law, respect for private property, open trade and investment, competitive markets, and efficient, effectively regulated financial systems.

Losing “free” would be an enormous step backward. All G-20 nations agreed to the above statement last November, so there is no good reason to change it if the U.S. objects. In the short run, it is easy to see how a negotiator might give this up for a more concrete immediate objective. In the long run, few things are as important. I hope the American team will insist on repeating this language, and in particular keeping the phrase “a commitment to free market principles,” as our negotiator did last fall.

Four of the five major topics of discussion at the summit are extensions and continuations of the November efforts. There is one big difference, influenced greatly by our new President. After reviewing the available press and talking with Dan Price, President Bush’s “sherpa” for the first G-20 summit last November, here are my expectations for the London G-20 summit.

- Global macroeconomic stimulus — The big difference is the new #1 agenda item for the G-20, global macroeconomic stimulus. President Obama’s first domestic economic policy effort was the enactment of a law that he argues will stimulate near-term macroeconomic growth. He is pushing other nations to take similar actions, and for the G-20 as a whole to support similar global efforts.I expect the final G-20 statement will broadly support national actions for macroeconomic stimulus, but will not include any numbers. It will say something like “Nations should do what is necessary.” It may also emphasize the fiscal actions already taken by a large number of nations.Reading between the lines of President Obama’s answer to a question in a press conference this morning confirmed this expectation.

- Financial market stabilization — I expect this will be a continuation of efforts in November, but with some details fleshed out. The final statement will likely highlight three subgoals to financial stabilization: restarting lending, enhancing the capital structure of financial institutions (aka recapitalizing banks), and dealing with toxic assets. This is consistent with discussions from last fall, but I expect a greater American emphasis on the last item from the new team.

- Regulatory reform – While financial market stabilization focuses on short-term actions the G-20 nations need to take, the regulatory reform section will focus on longer-term reforms to reduce the chance that these same problems recur in the future. The negotiators and their staffs have spent a lot of time on these issues, and I expect the final product will continue to flesh out the construct created last November, with a lot of details now filled in.I expect an emphasis on improving oversight and greater cooperation among national regulators. To my delight, I do not anticipate any mention of any sort of “single global regulator.” There is a so-called “college of supervisors” that was part of the November and prior efforts, but my expert advisors on this subject assure me that this group is about coordination, not the creation of a supra-national sovereign group. Participant nations appear interested in coordination of national efforts while maintaining national sovereignty. This is a big deal for me. Let’s work together, but Americans should have the final say in what America does.There is an interesting debate about “convergence” of national regulatory structures that underlies this question. I expect the statement will emphasize the goal of “convergent” regulatory structures. A tension exists between two goals. We want a level playing field across nations so that government policies distort capital flows as little as possible. In this respect, convergence of national regulatory structures can be a good thing. At the same time, if they converge to a consensus position that is unwise, then that’s a bad thing. My own instinct is to worry that, in a politically governed process negotiated by national governments and regulators, there will be a tendency to converge to a structure that is overly restrictive and burdensome. This is a tension that will play out in obscure international regulatory fora over months and years, and can have long-lasting and important consequences on the international flows of capital. I could be OK in theory with “convergence” language, if I knew what the final details would look like. Since no one can know that in advance, “convergence” language makes me nervous now, as it did last November.

I further expect that the regulatory reform section will talk about the importance of better oversight of “systemically important institutions” (read: too-big-to-fail) in ways that parallel how Secretary Geithner, and Secretary Paulson before him, and Chairman Bernanke, have spoken about the issue.This will send an international signal that the problem of regulation of institutions that are deemed to be too big to fail is a critical area for future policy development. My own view is that this is the big enchilada. I trace back much (most?) of our current financial pain, as well as almost all of the tension between Wall Street and Washington, to consequences from being on the back end of a too-big-to-fail problem, where all options are terrible. I think it’s our primary long-term financial policy challenge. I wrote about the causes of the financial crisis last October, following a speech by President Bush.

There is an important follow-on question about the relative importance of strengthening the oversight of huge banks and insurance companies on the one hand, versus expanding regulation into hedge funds and private pools of capital on the other. I am absolutely convinced that the former needs major reform. I am far less certain that the second is as large of a problem. I am in the minority in this view. This is a topic for further discussion.

I also anticipate that the final statement will say something on tax havens. My views here on international convergence of taxation differ significantly from those expressed in the past by those who are now senior American officials. I will refrain from commenting while they are overseas negotiating. They have the ball for America.

I expect the regulatory reform section will talk about the importance of moving the trading of Credit Default Swaps (CDS) onto organized exchanges, which parallels efforts that Secretaries Paulson and Geithner have pushed here in the U.S. This is a good and important thing.

I expect the statement will continue to flesh out work to harmonize accounting standards. This is simultaneously mind-numbingly boring and incredibly important.

There will also be some structural changes to the Financial Stability Forum – they will change the name to the Financial Stability Board and add more members from the G-20. They will also have language, I think, similar to that in the November document on executive compensation.

- Increased resources for the IMF and restructuring of the World Bank and IMF– One of the advantages of being Treasury Secretary is you get some leeway to push issues that are important to you. Secretary Geithner has spoken of tripling the IMF’s budget, and Prime Minister Gordon Brown has spoken of doubling it. We will see where the number ends up, but it’s clearly going to increase. I am interested to see how willing Congress will be to fund the increased U.S. contribution.They will also change the governance structure of the IMF and World Bank. I anticipate that China and other developing countries will get more weight in decisions of these international bodies, but only if they pay their share of the budgets. There is an important thematic here for China and India that crosses a range of international economic policy issues. In international negotiations, China and India sometimes try to have it both ways. Their negotiators argue they should have the same say in international economic policy questions as major developed economies like the U.S., Japan, and major European economic powers. At the same time, they plead poverty and argue that they cannot possibly sacrifice economic growth for the global good. My view is: in or out. You decide. If you want to be a first-tier economic nation, that’s fantastic. You play by the same rules as everyone else, and you make the same sacrifices for the global good. You cannot have it both ways.Finally, I anticipate the U.S. and Europe will give up what some call the “knightship rights” of choosing the leaders of the World Bank and the IMF. I expect one result will be some kind of new (supposedly) merit-based selection process.

- Fighting protectionism – This is the topic that I hope will make almost all of the G-20 leaders uncomfortable. In November the G-20 leaders agreed to a fantastic strong statement that opposed protectionism, in which they said,

We underscore the critical importance of rejecting protectionism and not turning inward in times of financial uncertainty. In this regard, within the next 12 months, we will refrain from raising new barriers to investment or to trade in goods and services, imposing new export restrictions, or implementing World Trade Organization (WTO) inconsistent measures to stimulate exports. Further, we shall strive to reach agreement this year on modalities that leads to a successful conclusion to the WTO’s Doha Development Agenda with an ambitious and balanced outcome. We instruct our Trade Ministers to achieve this objective and stand ready to assist directly, as necessary.

And yet on March 17th the World Bank reported that 17 of the G-20 nations “have implemented 47 measures that restrict trade at the expense of other countries.” The U.S. is one of the 20, and the World Bank highlighted “the US direct subsidy of $17.4 billion to its three national

[auto] companies.” President Obama’s Monday announcement extending the auto loans make this a challenging topic for him in London.I’d like to praise World Bank President (and former U.S. Trade Representative and Deputy Secretary of State) Bob Zoellick for this excellent and well-timed study. We need more “name and shame” tools to highlight protectionist actions by governments. The fragile world economy makes it even more important that everyone push for free trade and open investment.

Dan Price was President Bush’s international economic advisor in the White House, and also the President’s “sherpa” for the November G-20 summit. Dan suggests that President Obama could demonstrate U.S. leadership with a move that promotes both free trade and his clean technology agenda, by getting the G-20 nations to agree to eliminate tariffs on clean energy technologies. President Bush launched this effort last November, and it would be a huge win on multiple fronts for our new President if he could bring this to a successful closure. I strongly agree with Dan.

I conclude with a warning from Dan Price, who says, “In the process of needed reform, there is a risk of political demonization of particular products or services, like CDS or securitization, that in fact perform a very useful function.”

I wish President Obama and his team the best in their efforts to represent America at the G-20 summit.

Welcome, Instapundit, Wall Street Journal, Greg Mankiw, and National Review readers!

You’re probably here this morning either because of a link from Instapundit, or from Bill McGurn’s excellent Main Street column in today’s Wall Street Journal, or because of Yuval Levin’s kind reference on The Corner, or from Greg Mankiw over the weekend. However you may have found me, welcome!

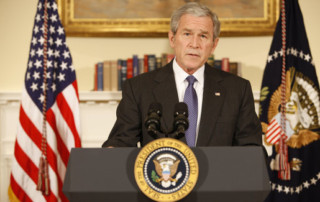

As background, I served as a White House economic advisor to President George W. Bush for more than six years, and ran the National Economic Council for him in 2008, in a position now held by Dr. Lawrence Summers.

While I plan to write about a wide range of economic policies over time, I’ve got two big series going on right now. The first is on auto loans, and the second is on the TARP.

- A deadline looms (background)

- The President’s options

- The Bush approach (which I coordinated for President Bush)

- Chyrsler gets an ultimatum, GM gets a do-over (analysis of President Obama’s Monday announcement)

- The press forgot to ask about the cost of the taxpayer

I hope you’ll sign up for the mailing list in the right sidebar.

Auto loans, part 5: The press forgot to ask about the cost to the taxpayer

As I explained yesterday in part 4 of this series, the President delivered different substantive messages to General Motors and Chrysler. I would like now to focus on one element of that message, because there’s an enormous hole in yesterday’s announcement, and it appears that the press missed it. It appears that the Administration did not say how much additional taxpayer funding it is committing over the next 60 days.

We do know from the President’s remarks and from the White House fact sheet that part of the message delivered to Chrysler was:

- We will subsidize you through April 30th so you have time to try to merge with Fiat.

- We’ll consider subsidizing the merger with Fiat by up to $6 billion of taxpayer funds, as long as we get paid back first.

We also know that part of the message delivered to General Motors was:

- We will “provide [you] with working capital for 60 days to develop a restructuring plan and a credible strategy to implement such a plan.”

The press could have reported yesterday’s story as, “President Obama today committed to put another $X billion of taxpayer funds at risk to save the auto industry, as he extended the loans provided by President Bush in December. He gave Chrysler a hard deadline, and promised taxpayers that they would spend no more than $Y billion to help Chrysler avoid bankruptcy. He made no similar commitment to taxpayers on General Motors, promising only that they would pay for at least enough to ‘provide [General Motors] with working capital for 60 days. These new commitments of taxpayer funds will come from the shrinking remainder of the $700 B of TARP funds appropriated by the Congress last September, leaving less to address the President’s goals in stabilizing the financial system.” I have seen no reporting like this, and I cannot see any evidence of the White House press corps asking what X and Y are.

Two reporters appear to have come close. In yesterday’s White House press briefing, one asked White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs the following:

Q: … One of the very big debt holders to these two companies right now is the United States government and the United States taxpayer. Is part of why it looks like the White House is being tougher on these companies the fact that that taxpayer money isn’t going to come back, because once you go into bankruptcy or writing down debt, the taxpayer money is also in jeopardy — unlike the banks, which claim they’re going to pay it back eventually?

…

Q: And are the taxpayers one of those stakeholders at this point that’s going to have to make an additional sacrifice?

MR. GIBBS: Well, I — the President believes that the decision will put these companies on the best path forward and ultimately putting them on that stable and strong path to where they’re regaining market share and they’re selling automobiles is the best way for the taxpayer to recoup the money that has been loaned to Chrysler and GM.

Yes, sir.

Q: For the taxpayer that you’re trying to protect, what can you tell that person will be different under the new management of GM that was not true yesterday?

MR. GIBBS: Well —

Q: What will Rick Wagoner’s departure mean in the next 60 days that was not achievable with him at the top of the company?

I compliment these two reporters for at least asking about the taxpayer. They just need to get a little more specific.

The President’s immediate actions were to extend the March 31st deadline to April 30th, as he is permitted to do by the terms of the loans we issued in December, and also to commit new but unspecified amounts of taxpayer funding to keeping GM and Chrysler from having to file for bankruptcy over the next 30 (Chrysler) and at least 60 (GM) days.

We do not know how much more these new commitments will cost the taxpayer (and squeeze the TARP). We know that $29.9 B has already been loaned or committed to these two manufacturers, their suppliers, and now auto parts suppliers:

($ B) Auto manufacturers …. General Motors $13.4 …. Chrysler $4 Auto finance companies …. GMAC(including $1B from US Treasury –> GM –> GMAC) $6 …. Chrysler Financial $1.5 Auto parts suppliers $5 Total $29.9 We also know that the Administration is willing to sweeten a Chrysler-Fiat deal by “up to $6 billion,” with a list of conditions. It appears that Sheryl Stolberg and Bill Vlasic misreported this in today’s New York Times as “will consider giving $6 billion in additional taxpayer aid.” There is a big difference between “up to $6 billion, if you meet certain conditions,” and “$6 billion.” The Administration has left themselves room to bargain with Chrysler-Fiat any number between $0 and $6 billion.

The White House staff deserve credit for managing the press to frame the story in a way that benefits the President.

- Sunday afternoon the press learned that General Motors CEO Rick Wagoner would be stepping down at the request of the White House. This is irresistible to the press.

- Sunday evening, reporters were briefed (I will guess by phone) by “senior officials.”

- Monday morning, the President gave his remarks.

Like a bird that cannot resist looking at a shiny object, the press focused their initial coverage on Mr. Wagoner’s departure. (I intend no disrepect to Mr. Wagoner by this comparison.)

The President’s remarks then gave them plenty of new material for their stories. Faced with impending deadlines and a tidal wave of new information, most of them combined the information they were given with some outside analysis, producing the coverage you see in today’s papers.

If you read Mr. Gibbs’ press briefing yesterday, you will see that almost all of the questions are about Mr. Wagoner’s departure, or about comparing the government’s treatment of the auto companies compared to its treatment of Wall Street firms. Today’s coverage discusses in detail what might happen to these companies 30 or 60 days from now. In contrast, I have seen no coverage about the ambiguity about how much new taxpayer funding the President has decided to spend now. If you have seen some coverage of this point that I missed, please let me know. I would like to compliment the reporter.

$30 B is a lot of money. This amount is going up, but we don’t know by how much. I hope someone else asks.

(Hint for reporters: If Administration officials tell you, “It’s uncertain,” ask what estimate the President was provided. There’s no way they went in to brief the President without at least having an estimate.)

Is $700 billion enough? Part 3: Secretary Geithner says we have more room

Last Friday I posted that I thought the Administration had less than $40 B of room remaining in the TARP. The Wall Street Journal reported today Monday that Treasury says “it has about $134.5 billion left in its financial-rescue fund.” Secretary Geithner addressed this question Sunday on This Week with George Stephanopolous.

GEITHNER: George, we have roughly $135 billion left of uncommitted resources. Less is out the door, but in terms of, if you look at what’s not committed yet, it’s roughly, you know, $135 billion.

Can we reconcile the two? If so, how?

We can piece some of it together from the public record. Here are the key data points:

- Geithner: “That estimate [of $135 B] includes a judgment, a very conservative judgment about how much money is likely to come back from banks that are strong enough not to need this capital, now, to get through a recession. But that’s a reasonably conservative estimate.”

- Wall Street Journal: “In its estimate, the Treasury projects that it will receive about $25 billion back from banks that have participated in TARP.”

- Wall Street Journal: “A Treasury official said Saturday that while the program could cost as much as $250 billion, the $218 billion number is a more-accurate estimate given that a key application deadline for the program has passed.”

The Secretary highlights an important but less well-known feature of the TARP. The law enacted last September limits to $700 B the Treasury’s net outlays at any one point in time. If Treasury gets money back from an investment, they can do something else with it.

Let’s begin by adding a column to my first table from last Friday. The right-most column marks in red the above two adjustments to the Capital Purchase Program (CPP) line, resulting in a new $193 B net estimate. The Administration has not signaled any changes to other elements of this table, and I don’t see how they could. The other funds have all been spent, so there’s not really any available discretion that I can see.

My Fridayestimate

Monday’sTreasurynumbers Banks — Capital purchase program $250 193 AIG $40 40 Citigroup $25 25 Bank of Amrerica $27.5 27.5 Autos ….GM $13.4 13.4 ….Chrysler $4 4 Auto finance ….GMAC(including $1B from UST –> GM –> GMAC) $6 6 ….Chrysler Financial $1.5 1.5 Term Asset-backed Lending Facility (TALF)for new securities for consumer credit $20 20 Subtotal, commitments duringthe Bush Administration

$387.4 $330.4 Now I’m going to take their new commitments and put them in tabular form, starting with the new $330.4 B figure above.

Subtotal, commitments duringthe Bush Administration 330.4 + new commitments bythe Obama Administration Additional AIG funds 30 Housing subsidies from TARP 50 auto parts suppliers 5 small business loans 15 Further TALF expansion forconsumer credit and mortgages 80 Public Private Investment Plan 75-100 Total 585.4 — 610.4 Remaining room within $700 B total 89.6 – 114.6 We need to get this range ($89.6 B — $114.6 B) up to the Secretary’s $134.5 B figure. To close this gap, we have only a few options:

- They dial back some of these commitments.

- There is overlap between the items on this table, so that they are, at least in part, non-additive.

- I’m missing something fundamental.

I do not see how they can dial back on the $30 B for AIG. I will assume I am not missing something fundamental. That means that the other items must overlap.

I will now start guessing. I will guess they are not going to change the $50 B number for housing, nor the $15 B for small business loans, nor the $5 B for auto parts suppliers. The obvious places for them to go are to start overlapping the big $80 B TALF figure with the other elements, and to squeeze PPIP.

I had assumed that the Administration’s publicly-stated “$100 B consumer and business lending initiative” was $20 B Bush + $80 B Obama, and that they added another $5 B for auto parts suppliers and $15 B for small business loans. Now I cannot see how that assumption is consistent with the Secretary’s statement that he has more room within the $700 B.

Look what happens if instead we assume that the $5 B and $15 B are a part of the “$100 B consumer and business lending initiative.” I will repeat this table with a new column. Let us also assume the lower $75 B figure the Obama team has used for PPIP, rather than the higher $100 B.

Subtotal, commitments duringthe Bush Administration 330.4 330.4 + new commitments bythe Obama Administration Additional AIG funds 30 30 Housing subsidies from TARP 50 50 auto parts suppliers 5 5 small business loans 15 15 Further TALF expansion forconsumer credit and mortgages 80 60 Public Private Investment Plan 75-100 75 Total 585.4 — 610.4 565.4 Remaining room within $700 B total 89.6 – 114.6 134.6 We have hit the Secretary’s figure within $100 M. To summarize, this means that a plausible explanation for the Secretary’s figure is:

- They are assuming no more funds go out the door in the Capital Purchase Program, beyond the $218 B that already has been invested.

- They are assuming “a conservative” $25 B of the existing investment will be repaid by the time they need it for something else.

- The TALF subsidy for new securitizations is only $80 B, rather than the $100 B I (and others?) had previously thought.

- But the Consumer & Business Lending Initiative is still the advertised $100 B, because they count the $5 B for auto parts suppliers, and the $15 B for small business loans, as part of that $100 B total.

- The PPIP is at the low end of the Administration’s range ($75 B), rather than the high end ($100 B).

I need to emphasize that I do not know these last three items. They are educated guesses about how to back into the Secretary’s publicly stated number.

I am also left with one huge uncertainty. I don’t know where the TALF subsidy for the purchase of toxic assets goes. Is it a subset of the $80 B TALF number I’m assuming, in which case there’s less TALF available for new securitizations? Or is it a subset of the $75 B number I’m assuming for the PPIP, in which case there’s less available for equity investment?

So was I wrong last Friday? There are three possibilities:

- I was wrong.

- Circumstances changed.

- While over the past several weeks the Administration has emphasized the size of their new programs, they are now looking for flexibility so they can maximize their chance of avoiding another request of Congress. They know that Congress is in a foul mood about the TARP, and are therefore looking to emphasize this flexibility by stating the largest number they can justify.

I think it’s #3. The Administration needs to balance the needs of the market with what is feasible from the Congress. Given recent AIG coverage, they are now leaning hard in the maximum flexibility direction. If this direction is sustained, I think the cost will fall upon the new programs, the TALF expansion and the PPIP, which would have to be smaller than some market participants may expect.

Auto loans, part 4: Chrysler gets an ultimatum, GM gets a do-over

President Obama spoke about loans to the auto industry at 11 AM this morning in the Grand Foyer of the White House.

In the first three parts of this series, we (1) covered some background, (2) analyzed the President’s options, and (3) learned about the loans President Bush authorized in December, which laid the groundwork for President Obama’s decision.

An Associated Press headline reads, “GM, Chrysler Get Ultimatum from Obama on Turnaround.” I think this is a misread. It appears to me that Chrysler got an ultimatum, and GM got a do-over.

Here’s my analysis of the different messages to Chrysler and General Motors contained in the President’s remarks and in the fact sheet released by the White House. I’m trying to weed out the political and communications signals the White House might want the press and various constituencies to think they heard, from the definitive and binding statements made today by the President and by his Administration. As an example, while the President’s words and the documents tip their hats to more fuel efficient vehicles, I see no specific new hard fuel efficiency requirements for either Chrysler or GM. This is in contrast to the clear language that Chrysler will get more funds after April 30th only if it has merged with Fiat or someone else.

In 6+ years working for President Bush I wrote and edited hundreds of White House fact sheets, and worked with the speechwriters and fact-checkers on a similar number of Presidential speeches. We meant exactly what we said in those speeches and documents. Here is my attempt to boil down the text of the President’s remarks and the White House fact sheet into their essential, definitive, and binding statements.

Message to Chrysler:

- You are not viable as a standalone company.

- We do not think that you can become viable as a standalone company. “[W]e have determined … that Chrysler needs a partner to remain viable.”

- We will subsidize you through April 30th, so you have time to try to merge with Fiat. (How much?)

- We’ll consider subsidizing the merger with Fiat by up to $6 billion of taxpayer funds, as long as we get paid back first.

- If that does not work and you can’t find another merger, you’re on your own.

- We will not subsidize you as a standalone company beyond April 30th.

- Your “best chance at success may well require utilizing the bankruptcy code in a quick and surgical way.”

- We will guarantee your warrantees for all new cars you sell.

Then there is a more detailed and quite specific set of terms. “Fiat, Chyrsler and all of Chrysler’s stakeholders must clearly understand that for this deal to succed, significant hurdles must be cleared…”

- Chrysler must, at a minimum “extinguish the vast majority of [their] oustanding secured debt and all of its unsecured debt and equity…”

- Chrysler, Fiat, and the UAW need to reach an agreement that entails greater concessions than those outlined in the existing loan agreements.”

- “Chrysler and Fiat need to demonstrate with a greater degree of detail an operating plan that is truly viable, that can generate meaningful positive cash flow in a normal business environment and that can demonstrate credibly that taxpayer loas will be repaid on a timely basis.”

- You’ll get no more than $6 billion, and that only after you’ve restructured.

- You have to make sure you can finance cars purchased by your dealers and customers.

- You need to have a credible plan. “Given the magnitude of the concessions needed, the most effective way for Chrysler to emerge from this restructuring with a fresh start may be by using an expedited bankruptcy process as a tool to extinguish existing liabilities.”

Message to General Motors:

- The plan you submitted does not propose a credible path to viability.

- There is a potential plan that will make you viable as a standalone company.

- We will “provide [you] with working capital for 60 days to develop a more restructuring plan and a credible strategy to implement such a plan.” (How much?)

- We will guarantee your warrantees for all new cars you sell.

- Your CEO, Rick Wagoner, has to resign. A majority of the board has to go as well.

- Your “best chance at success may well require utilizing the bankruptcy code in a quick and surgical way.”

- We (the U.S. government) will be involved in your restructuring. “The Administration team, consisting of Treasury officials as well as private sector auto industry and restructuring experts retained by the Administration, will work closely with the company.”

The clearest contrast I can provide is in these two sentences from the President’s remarks:

But if [Chrysler] and [its] stakeholders are unable to reach such an agreement, and in the absence of any other viable partnership, we will not be able to justify investing additional tax dollars to keep Chrysler in business [after April 30].

…

What we are interested in is giving GM an opportunity to finally make those much-needed changes that will let them emerge from this crisis a stronger and more competitive company.

Let’s put this in the context of the options I laid out in part two of this series. Remember that option 1 is to continue loaning GM or Chrysler taxpayer funds even if they are not yet viable, while option 2 is to provide taxpayer funds only after a firm has entered a Chapter 11 restructuring (aka “debtor-in-possession financing,” or “DIP financing”).

- On Chrysler, the President chose option 1, while making a hard commitment to a variant of option 2 after April 30th. He has locked himself into this strategy, even if it means that Chrysler fails and liquidates.

- On General Motors, the President has chosen option 1, and explicitly threatened option 2 after 60 days, but has left himself room to wiggle out of option 2 if he thinks that it might lead to GM’s liquidation.

If you disagree with my interpretation, I’d like to hear a different view. Please provide specific textual references to the President’s remarks or the White House documents. I would like to rely on primary sources rather than the press filter.

I hope to post some more on the additional exposure to taxpayers, as well as provide more of my own analysis. Check back later tonight if you’re interested.

If you’re new to this series, here are the three prior posts:

Auto loans, part 3: the Bush approach

The White House press office announced this evening that the President will speak about the auto industry tomorrow (Monday), at 11 AM, in the Grand Foyer of the White House.

The press is reporting that General Motors CEO Rick Wagoner has agreed to step down at the request of the Administration.

If you have read the first two parts of this series, then you have some background, and you understand the cost and benefits of the options the President faces.

As you hear news about the President’s announcement tomorrow, it may help you to consider the approach taken by President Bush. The loans we provided in December set the initial conditions and context for President Obama’s decision.

Here are President Bush’s remarks from December 19th when he announced the loans. First, he talks about the hard choice:

This is a difficult situation that involves fundamental questions about the proper role of government. On the one hand, government has a responsibility not to undermine the private enterprise system. On the other hand, government has a responsibility to safeguard the broader health and stability of our economy.

Addressing the challenges in the auto industry requires us to balance these two responsibilities. If we were to allow the free market to take its course now, it would almost certainly lead to disorderly bankruptcy and liquidation for the automakers. Under ordinary economic circumstances, I would say this is the price that failed companies must pay — and I would not favor intervening to prevent the automakers from going out of business.

But these are not ordinary circumstances. In the midst of a financial crisis and a recession, allowing the U.S. auto industry to collapse is not a responsible course of action. The question is how we can best give it a chance to succeed. Some argue the wisest path is to allow the auto companies to reorganize through Chapter 11 provisions of our bankruptcy laws — and provide federal loans to keep them operating while they try to restructure under the supervision of a bankruptcy court. But given the current state of the auto industry and the economy, Chapter 11 is unlikely to work for American automakers at this time.

Now he highlights an important concern that existed in December, but should no longer exist. This is an important change that should affect President Obama’s consideration:

Additionally, the financial crisis brought the auto companies to the brink of bankruptcy much faster than they could have anticipated — and they have not made the legal and financial preparations necessary to carry out an orderly bankruptcy proceeding that could lead to a successful restructuring.

We (President Bush’s advisors) counseled him in December that a Chapter 11 bankruptcy/restructuring filing was highly likely to lead to liquidation, because the firms (especially GM) weren’t ready for it. Everyone wants the companies to restructure successfully outside of bankruptcy, but they may be unable to do that with their stakeholders. To maximize your chance of a successful restructuring through bankruptcy, you need to prepare a legal, financial, and operations strategy for a Chapter 11 filing. I was astonished that a firm whose management had approached us in October about a possible bankruptcy filing (GM) had not yet prepared for it, but they had not. This meant that a DIP-financing option, implemented in late December, had an extremely high probability of leading to rapid liquidation. Here’s President Bush again:

The convergence of these factors means there’s too great a risk that bankruptcy now would lead to a disorderly liquidation of American auto companies. My economic advisors believe that such a collapse would deal an unacceptably painful blow to hardworking Americans far beyond the auto industry. It would worsen a weak job market and exacerbate the financial crisis. It could send our suffering economy into a deeper and longer recession. And it would leave the next President to confront the demise of a major American industry in his first days of office.

And so President Bush decided to provide loans to GM and Chrysler, and to their finance companies. Notice both points — they’re important:

A more responsible option is to give the auto companies an incentive to restructure outside of bankruptcy — and a brief window in which to do it.

… These loans will provide help in two ways. First, they will give automakers three months to put in place plans to restructure into viable companies — which we believe they are capable of doing. Second, if restructuring cannot be accomplished outside of bankruptcy, the loans will provide time for companies to make the legal and financial preparations necessary for an orderly Chapter 11 process that offers a better prospect of long-term success — and gives consumers confidence that they can continue to buy American cars.

These companies have now had “a brief window” to put in place plans to restructure into viable companies. We defined a “viable firm” in the loan terms as a firm that has a positive net present value without additional taxpayer assistance — in other words, the firm would be worth something if the taxpayers were to stop subsidizing it. If it were to meet this test, we believed that it could get private financing for its short-term operations.

The Obama Administration is required by the terms of the existing loans to determine whether they think the firms’ plans meet that test. By Tuesday, or by late April if the President so chooses, the Obama Administration must determine whether these firms can survive without additional ongoing taxpayer funding.

The companies have also had time to prepare for an “orderly Chapter 11 process,” so the DIP financing option (#2) should now be feasible, when it was not in December.

What we tried to do was set a hard deadline of March 31st, with only the flexibility to extend it to April 30th. To put it in the context of the options described in part two, we were implementing option 1 to buy the companies time to both negotiate with their stakeholders, and to prepare for a DIP-financing Chapter 11 restructuring if those negotiations failed to produce a company that could survive without ongoing taxpayer funding.

Our hope was that the Obama team would be able to use the deadline of our loans as a bad cop to force tough negotiations. We’ll see tomorrow how they did.

I imagine the news, and possibly the President’s remarks, will focus on the hard choices that have been made in the negotiations. Rick Wagoner’s resignation is a part of that story. If the changes are significant, then the Obama team should be complimented for them. I argue, however, that “look at how far we have come” is the incorrect metric. What matters instead is, “Do the companies still need taxpayer funding to maintain ongoing operations? If so, for how long is the President willing to provide those taxpayer funds? Is there a limit, in time or in dollars?”

We all want the companies to make the hard choices needed to restructure and become profitable again. The hard question is, “For how long are you willing to continue subsidizing them, if they’ve done a lot, but still not enough to stand on their own?”

Health spending fallacy

The President emphasized the importance of health care reform in Tuesday evening’s press conference. One of his arguments was that reforming health care would help address federal and state government fiscal problems:

What we have to do is bend the curve on these deficit projections. And the best way for us to do that is to reduce health care costs. That’s not just my opinion; that’s the opinion of almost every single person who has looked at our long-term fiscal situation.

His statement is excellent but incomplete. There are two problems driving future deficits: rising health care costs, and the aging of the population. Both factors drive projected Medicare and Medicaid spending increases, and demographics helps drive projected Social Security spending increases. To fix our long-term deficit problem, we need to address both factors, and spending trends in all three programs.

The President then defended the increased health spending proposed in his budget:

What we’ve said is, look, let’s invest in health information technologies; let’s invest in preventive care; let’s invest in mechanisms that look at who’s doing a better job controlling costs while producing good quality outcomes in various states, and let’s reimburse on the basis of improved quality, as opposed to simply how many procedures you’re doing. Let’s do a whole host of things, some of which cost money on the front end but offer the prospect of reducing costs on the back end.

This is the health care investment myth: if only government will spend more money on health care, then that will reduce costs and, eventually, government health spending.

The correct response is a tautology: if government spends more money on health care, then government health care spending will go up, not down.

The President argues this spending is an investment that will address the sources of health care cost growth and “ultimately” drive down costs for the federal and state government. I dispute that, and will expand on my argument in the future.

But there’s a more important point. The President’s budget would increase health spending by $634 B over ten years. That’s a full order of magnitude larger than the current law program to subsidize health insurance for children (known as “S-CHIP”). You cannot spend $634 B on health IT, preventive care, and outcome measurement. You’ll run out of things on which to spend it.

When you’re setting aside that enormous sum, you’re doing it to expand taxpayer-subsidized health insurance coverage, as the Congress began to do in the so-called stimulus bill. That’s a policy choice that I’m happy to debate. But it is irrefutable that an expansion of taxpayer-funded health insurance coverage will dramatically increase government spending on health care, not reduce it.

The flawed logic goes like this:

- Health care spending is a big problem for government finances.

- Therefore, we will increase health spending in the federal budget to cover more people.

Proponents of this argument point out that federal, state, and local governments indirectly subsidize the uninsured through subsidies to cover some of the costs of uncompensated care (in clinics and hospital emergency rooms). By subsidizing health insurance coverage, they argue, we will keep them out of the emergency room and reduce total health care spending. They claim that we can cover more people and reduce spending without hurting anyone (except the taxpayer who is footing the bill).

This is incorrect, for three reasons:

- People receive more and better medical care if they have health insurance than if they are relying on free care. That’s a good thing for those people. It’s also more expensive for the payor.

- Every proposal to expand taxpayer-subsidized health insurance would have the government pay all or almost all of the cost of health insurance, while today the government pays only part of the cost of charity care.

- Medical expenditures tend to be highly concentrated in a relatively small proportion of the population. For each uninsured catastrophically sick person whose costs go down because they are receiving better or preventive care, you will get many more who would not use medical services if they were free, but will do so if someone else pays for it. When government is subsidizing pre-paid health insurance, the taxpayer will spend a lot to pay the premiums of a healthy previously uninsured person who may use no medical care at all. In the aggregate, government spending on heatlh care will increase.

Some argue that it’s worth it — that we have a moral obligation as a society to ensure that everyone has health insurance. That’s a separate question. I am instead disagreeing with the budgetary point. Expanding taxpayer-subsidized health insurance coverage by $634 B will increase government spending on health care, not reduce it. The President’s proposed $634 B health reform fund would severely worsen our long-term entitlement spending problem.

If this subject interests you, the best health policy writing I know is Jim Capretta’s blog Diagnosis.

Auto loans, part 2: options for the President

In part one of this series I reviewed some background and long-term problems facing the U.S. auto manufacturers. I pointed out that General Motors and Chrysler, and the Obama Administration, face a more immediate cash flow problem. The Obama Administration is in the midst of rolling out the President’s new game plan. I’d like to walk you through the options the President faces.

Now let’s examine the benefits and costs of each option. I will soon ask you to pick your own recommendation to President Obama.

Option 1: Extend the current loan and lend additional funds from TARP

Assume a loan cost of roughly $5 B per month for GM, Chrysler, and their finance companies combined. This could be off by a factor of two either way, and can easily vary from one month to the next as external pressures on the companies change their needs.

Likely short-term outcome: 99% chance GM and Chrysler continue operating for the duration of the loan.

Benefits

- It avoids immediate failure and the associated job loss. If GM and Chrysler both were to enter a Chapter 7 bankruptcy and shut down operations permanently, we had estimated (back in December) total job loss of roughly 1.1 million jobs, heavily concentrated in Michigan and surrounding states. This would be a significant hit to an overall weak national economy, and would devastate the region. We further estimated that U.S. GDP would be 0.5 — 0.75 percentage points lower in 2009 as a result.

- It buys the firms time to continue working to solve the above-described long-term problems. It also buys time to allow the economy to recover, with the hope that vehicle sales improve.

- It buys the President and his team time to focus on implementing and selling their financial plan, passing their budget through Congress, and maybe asking Congress for additional TARP funds.

Costs

- The taxpayer would be placing at risk more funds ( ?$5 B per month), in addition to the $25 B already loaned in December and January.

- New loans would consume scarce TARP resources, which are needed for the banking sector (their original intended purpose).

- The December loans require the firms to prove that they are “viable” to continue receiving funds beyond March 31st. By rewriting or extending these loans, the President risks taking a political hit for explicitly relaxing or delaying the viability requirement. By providing even more taxpayer funds, he exacerbates this risk.

- By temporarily removing the threat of a bankruptcy filing, it may delay a deal among stakeholders (labor, dealers, suppliers, creditors, and management).

- Each time the taxpayer injects funds, it reinforces the incentive for those stakeholders to negotiate with the government (both the Administration and, separately, with the Congress) rather than with management.

- In a competitive market, management and equity holders are supposed to face the full downside risks of their failures. By insulating them from some of that downside, the government is creating a moral hazard for the future. This is the “bailout” point, applied to management and shareholders.

- It is harder to say no to other industries and firms that request relief. The Obama Administration already said yes to certain auto suppliers, lending them $5 B of TARP funds [last week]. This is a slippery slope.

- It is harder to justify saying no the next time. If you lend them funds for another three months, how do you justify saying no three months from now? Each extension and additional loan increases the chance of these becoming “zombie firms” — firms which can survive only by consuming an ongoing stream of taxpayer subsidies.

Option 2: Offer to extend the current loan, and lend additional funds, but only to help a firm that attempts a restructuring by filing for bankruptcy.

This is called “debtor-in-possession” financing, or DIP financing. The firm enters a Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceeding, and then someone shows up and provides the cash for them to continue operating. In this case, that someone would be the U.S. taxpayer, through the TARP.

Assume that, as a part of this option, some of the DIP financing goes to support a guarantee of service (from third party services, if necessary) for cars bought during restructuring. This should help address the bankruptcy purchase fear.

You should assume a significantly higher initial cost to the taxpayer: $20 B up front, and $100 B total over time, if GM and Chrysler both did this. When a firm enters bankruptcy, everybody wants cash up front for everything. So the taxpayer outlay of DIP-financing is equivalent to roughly 10-12 months of ongoing support in option 1.

Likely short-term outcome: GM files for bankruptcy and takes the DIP financing. Chrysler files for bankruptcy. Maybe they take the DIP financing, or maybe their primary shareholder, the private equity fund Cerberus Capital Management, liquidates them and sells off the valuable parts.

Possible medium-term outcomes: This is where it gets tricky. The bankruptcy restructuring process creates a greater likelihood of the firm reducing its costs dramatically, at the expense of other stakeholders: labor, creditors, and dealers would all take significant hits, because the bankruptcy judge can void their existing contracts. This improves the firms balance sheet, and can improve their cost structure.On the other hand, bankruptcy means the firm defaults on payments to suppliers, which may hurt their ability to get new supplies and increase their costs. In addition, the conventional wisdom is that the word “bankruptcy” in headlines will make it harder for that firm to sell cars, as customers will be (rightly) concerned that the firm may not exist to service their car in the future. It’s unclear how these factors would balance out: will the benefit of cost savings from reorganization and reductions in legacy costs outweigh higher supplier costs and lost sales?

We guessed that there would be a high probability of a Chapter 11 restructuring leading to a Chapter 7 liquidation. This is particularly true when aggregate vehicle sales are so low — sales in 2009 are down about 38% from a year ago. GM’s sales so far this year are down 51% compared to last year; Ford’s are down 45%, and Chrysler’s are down 49%.

If, instead a restructured firm emerges from Chapter 11, it probably has a higher probability of longer-term success than if it had not entered Chapter 11, because it was probably able to achieve greater cost savings and potential future productivity improvements.

Benefits

- It may avoid immediate failure (liquidation) and the associated job loss.

- It buys the President and his team time to focus on implementing and selling their financial plan, passing their budget through Congress, and maybe asking Congress for additional TARP funds.

- If the firm survives Chapter 11 restructuring intact, it probably has a higher probability of being viable in the long run.

- If the firm survives restructuring, the taxpayer has a higher probability of being repaid.

- Equity holders face the full costs of the firm’s failure. No more moral hazard is created.

Costs

- There is a fairly high probability that at least one of GM and Chrysler liquidate. Chrysler’s owners might choose to do so immediately. Either firm may find that their sales loss is so great that they cannot emerge from restructuring, especially beginning from an already low level of sales. If they liquidate, then a portion of the 1.1 million job loss happens, with consequent economic and political effects.

- This is a bigger cash outlay from the taxpayer than under option 1, at least initially. If these are TARP funds, a $100 B outlay squeezes out an element of the Administration’s financial and housing plan. If not, it dramatically increases the likelihood that the Administration has to go to Congress for more funds.

- The President would be blamed for “allowing the U.S. auto industry to go bankrupt,” even if the firm is in restructuring and trying to emerge from bankruptcy. The word “bankruptcy” has tremendous political power. The President’s team might try to shift the blame back to his predecessor, but the failure would have occurred on his watch. This would have a national impact on the rest of his agenda, and would have a severe regional political cost for the President, especially in Michigan and neighboring states. It would also likely force some Members of Congress of his own party to attack him publicly. It is easy to imagine midwestern Democrat Members voting no on the budget resolution in protest of a Presidential decision not to provide further aid.

Option 3: Allow the loan to be called and provide no additional funds.

Likely short-term outcome: GM and Chrysler file for bankruptcy no later than mid-April.

Likely medium-term outcome: GM and Chrysler likely liquidate.

Benefits

- U.S. auto manufacturers succeed or fail based on their own merits, and are therefore on a level playing field with most other American firms. (I said “most.”)

- There’s no additional direct cost to the taxpayer. There would be indirect costs from higher unemployment insurance payments, higher health insurance subsidies through “COBRA”, and lost income tax revenues.

- There’ no more moral hazard. Investors and managers face the full costs of their actions and decisions (present and past).

Costs

- Assume roughly 1.1 million lost jobs, beginning within weeks.

- (Same as option 2, but more intensely): The President would be blamed for “allowing the U.S. auto industry to go bankrupt.” His team might try to shift the blame back to his predecessor, but the failure would have occurred on his watch. This has a national impact on the rest of his agenda, and would have a severe regional political cost for the President, especially in Michigan and neighboring states. It would also likely force some Members of Congress of his own party to attack him publicly. It is easy to imagine midwestern Democrat Members voting no on the budget resolution in protest of a Presidential decision not to provide further aid.

Option 4: Punt to Congress. Refuse to spend additional TARP money, and tell Congress that if they want the companies to survive, they should appropriate new funds.

Given that the December loans expire within a week, the practical implementation of this option is likely a combination of this with option 1: extend the December loans for, say, one additional month, and provide additional TARP funding to cover that month. But tell the Congress and the auto manufacturers that you will not lend any funds beyond that without a new law from Congress that explicitly appropriates those funds.

Likely short-term outcome: GM and Chrysler survive for as long as you provide your last short-term loan.

Likely medium-term outcome: Completely unknown.

Benefits

- Some argue that TARP funds were never intended for this purpose, and that Congress has the power of the purse. This is a decision, they argue, that should be made by the Legislative branch, not the Executive branch. Your decision not to spend any more (beyond, say one additional month) of TARP funds returns both the policy and political responsibility “where it belongs.”

Costs

- Reactions from Congress will be mixed.

- Conservatives (not usually this President’s allies) will likely relish the opportunity to try to block or amend legislation. Environmental advocates may take a similar view.

- Members from auto states, as well as the auto manufacturers themselves, will likely try to pressure you and the President to reverse this decision, “Just as a fallback, in case Congress does not act.” This pressure will come from friends of labor and management, as well as from investors and “the markets” generally.

- You lose control of the outcome, which is highly uncertain. In past years, the smart money would have bet heavily on the firms getting additional relief, and that’s still probably a better than 50 percent chance. But in last Fall’s debate there were signs of bailout fatigue on both sides of the aisle, and the environmental advocates had powerful friends who were not sympathetic to the industry’s views.

- You look like a wimp who is trying to duck responsibility.

Coming soon: parts 3 and 4, comparing the Bush and Obama approaches, and part 5, in which I pose some hard questions and ask you to make your recommendation to the President.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]