Leader Reid’s version of health care reform

Here is the bill text, all 2074 pages of it.

Here is the Joint Tax Committee estimate of the revenue effects.

I will update this post with a link to the CBO score when it’s available. Here is a document that I am told was handed out to Senate Democrats at their caucus meeting this evening. It appears as if it were drafted by Leader Reid’s staff. I believe this document is the basis for this evening’s news reports that “CBO says the bill costs $849 billion.” It is inaccurate for a news organization to report that CBO says this until they have seen an official CBO document.

Update: Here is my analysis of the tax increases in the bill.

Update 2: Here is CBO’s estimate.

Updated health care projections

I am lowering from 60% to 50% my projection for the success of comprehensive health care reform.

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the House and through the regular Senate process with 60, leading to a law; (was 40% -> 30%)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the House and through the reconciliation process with 51 Senate Democrats, leading to a law; (steady at 20%)

- Fall back to a much more limited bill that becomes law; (was 20% -> 15%)

- No bill becomes law this Congress. (was 20% -> 35%)

I think there is zero chance a bill makes it to the President’s desk before 2010. If a bill were to become law, I would anticipate completion in late January or even February.

The next few days

Later today Senate Majority Leader Reid is expected to release his version of the health care reform bill along with a CBO score. Senate Democrats are scheduled to meet (“caucus”) late this afternoon. My sources tell me that most Senate Democrats do not know what is in the Reid amendment. Release of the Reid amendment and the caucus meeting are two pivot points that can significantly shape prospects for the bill.

Leader Reid will be asking all 58 Senate Democrats, along with Independents Lieberman and Sanders, to vote for cloture on the motion to proceed this Friday or Saturday. Here is how I would expect the process to play out:

- Today: Leader Reid moves to proceed to an unrelated House-passed tax bill. He then files a cloture motion (signed by 16 Senators) on the motion to proceed.

- Friday: The Senate votes on cloture on the motion to proceed. If Reid gets 60 votes to invoke cloture, then 30 hours of post-cloture debate begins. That takes us to Saturday afternoon.

- Saturday: There’s an up-or-down (majority) vote on the motion to proceed. Assuming cloture was invoked Friday, this vote is a gimmee. It might even be a voice vote that does not require Senators to be present.

- After the motion to proceed is adopted on Saturday, the Senate would be debating the unrelated House bill. Reid would then offer his new proposal as a complete substitute amendment for the text of that bill, sometimes colloquially referred to as the shell bill. Leader Reid’s proposal would be referred to as the Reid substitute. You can think of it as the Reid bill.

- The amendment (probably approaching 2,000 pages) needs to be read in full. I assume Leader Reid would ask for unanimous consent to dispense with the reading of his amendment. I would then expect a Republican (McConnell? Coburn?) to object.

- Saturday – Monday?: The Senate clerks would take turns reading the entire Reid substitute amendment aloud.

- Monday: The amendment would have been read, and the Senate would adjourn until Monday the 30th.

- Monday, Nov. 30: The Senate would convene and begin consideration of the Reid substitute.

Advantages for Leader Reid of starting now:

- If he gets 60 votes on cloture on the motion to proceed, he has a win going into the Thanksgiving recess, having held his entire party together. This creates positive momentum.

- He allows himself more time in December for debate and amendments.

- In December he is inoculated against process arguments about having had insufficient time to read and understand his amendment. By the 30th the amendment would have been public for 12 days.

Disadvantages for Reid of starting now:

- A Friday cloture vote would break the 72-hour transparency commitment he made to his moderates. This might cause a bump or two within his caucus, but he can solve it by delaying the cloture vote until Saturday night.

- He may be rolling the dice on the upcoming cloture vote. I have been surprised that some of his 60 have been willing to leverage their votes on the motion to proceed to push for substantive concessions. It is highly unusual to challenge your own party leader on the motion to proceed.

- Q: Does he already know he has 60 for a Friday (or Saturday) cloture vote, or is he betting that he can round up 60?

- Q: Do some of those 60 votes depend on substantive policy that they have not yet seen? If so, the substantive and mechanical challenges of rounding up the votes by Friday are significant.

- He is exposing his members to a lot of risk over the Thanksgiving recess. They will spend 9-10 days at home being hammered on a bill that many/most of them may have not yet seen. Imagine a constituent asking you, “Why did you vote for [cloture on the motion to proceed to] the Reid bill when it contains _________?” In reaction, a nervous Senate Democrat might reply, “I agree with you. I just voted to start the process, but I won’t vote for cloture in December unless that is fixed.” Winning the battle this week may make it harder for him to win the war in the third week of December.

- Constituencies have more time to analyze the bill, organize their campaigns, and lobby Members. This makes December more difficult.

Nevertheless, the odds favor Reid invoking cloture on the motion to proceed this Friday or Saturday. If that falls apart, then Reid and the bill are in trouble, because Democrats will be going home in chaos, and could not complete Senate floor action in December.

It is also interesting that Leader Reid is using an unrelated House bill as the shell, rather than the House bill. I am fairly certain that is because some of his members don’t want to take any vote even indirectly related to the House-passed bill. This is an indication of overall strategic weakness and substantive differences between the House and Senate.

Looking forward to December

Assume that Leader Reid is successful and the Senate spends three six-day weeks in December debating and amending the Reid substitute amendment. I would expect that as the third week approaches, Reid would begin to signal that the Senate has worked hard on the bill and needs to bring debate to a close. Around the middle of week three, he would file a cloture motion on his substitute amendment, with the cloture vote happening on or near Friday, December 18th.

That vote, cloture on the Reid substitute, is the vote. If Reid can get 60, then the Senate will pass a bill and the probability of a signed law goes way up. If he cannot get 60, the path is murky, but his chances for success go down.

My projections therefore depend heavily on my guess about that vote. It is nearly impossible to predict because you can tell two equally strong stories that point to opposite results:

- Pointing in favor of cloture on the Reid substitute: Independent of the policy substance and the home-state politics, how many Senate Democrats (and Independents) have the guts to vote no on cloture on December 18th after receiving a phone call from (or having an Oval Office visit with) the President? I can think of only one for certain. 60 votes of support for this bill could results from Democratic party loyalty to and fear of the President.

- Pointing against cloture on the Reid substitute: Were this not the President’s top priority in year one, this bill would have died weeks ago. The politics are a sure loser for almost any moderate Democrat, and the substantive attacks are effective and brutal. Like most, I expect the Reid amendment will lean left, causing serious policy concerns about higher taxes, higher premiums, government interference, more spending and long-term deficit risk for Democrats who think of themselves as fiscally conservative. In addition, most voters are focused instead on the poor labor market picture.

I have lowered my projection of Leader Reid succeeding for three reasons:

- Pretty much everything has to go right for him to win on cloture in mid-December. He has no more wiggle room on the schedule, and new intra-Democrat policy fights are popping up.

- I think his members are going to get beat up about health care and jobs over Thanksgiving recess, then return to Washington to face another bad jobs day Friday the 4th.

- If moderates demand large substantive concessions for their votes, liberals like Senators Rockefeller and Boxer may refuse. They may tell Reid they will oppose cloture if the bill moves toward the center, and instead advocate abandoning regular order and starting a clean reconciliation process in January. House liberals might join this effort.

Questions

- Does Leader Reid already know that he has 60 votes for cloture on the motion to proceed?

- Will the substance of his amendment affect that vote count?

- Will he include a payroll tax increase in his amendment, as is rumored?

- How badly will his moderate members get beat up over Thanksgiving break?

And when we get to mid-December,

- Will he have 60 votes for cloture on the Reid substitute?

- Suppose he knows he has 57-59 votes, with 1-3 undecided. Will he gamble?

- Suppose he knows he does not have 60, so he knows he would lose a cloture vote right before leaving town. Does he have the vote anyway?

- If he loses a cloture vote, what happens in January, and who has the whip hand in deciding?

Thursday morning update: Leader Reid did not file cloture on the motion to proceed yesterday. Assuming he does today, slip the above schedule by one day, with the cloture vote to occur Saturday.

(photo credit: Democrats.Senate.Gov video clip)

The House-passed bill’s effects on health insurance coverage

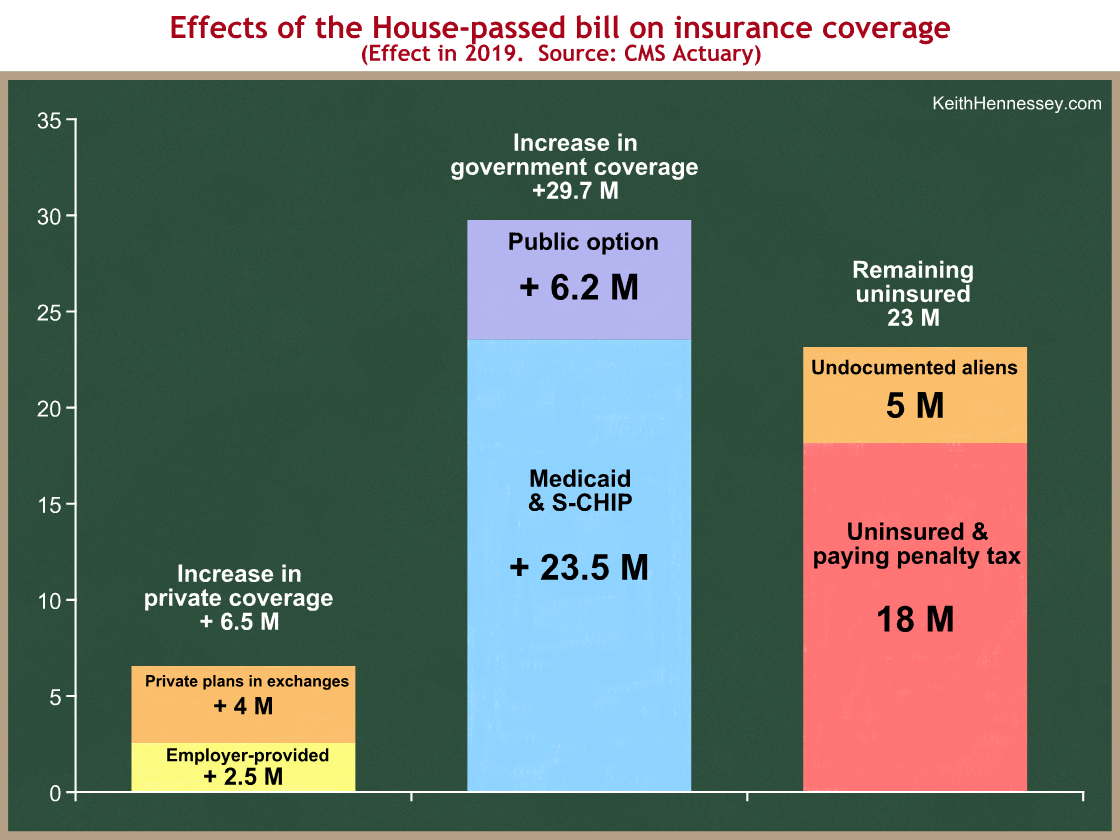

Saturday the Chief Actuary of Medicare & Medicaid, Rick Foster, released his estimate of the effects of the House-passed health care reform bill. His memo shows how H.R. 3962 would affect the number of people with different types of health insurance in the year 2019. I made a picture of the most interesting effects, grouping the newly covered people into private coverage vs. government coverage. As always, you can click on the graph for a larger version.

You can see that the largest effects of the House-passed bill on insurance coverage are:

- The bill would mean almost 30 M new people in government-run insurance, more than four times as many as would be newly insured through private coverage.

- By far the largest effect of the bill would be to enroll more than 23 M new people in two existing government programs, Medicaid and S-CHIP. Medicaid is today widely regarded as fiscally unsustainable before adding more people.

- Foster estimates that 18 M people would remain uninsured and have to pay the penalty tax. These people are clearly worse off than they would be under current law.

Here is Foster on the 18 M uninsured:

For the most part, these would be individuals with relatively low health care expenses for whom the individual or family insurance premium would be significantly in excess of the penalty and their anticipated health benefit value. In other cases, as appears to happen under current law, some people would not enroll in their employer plans (or take advantage of the Exchange opportunities) even though it would be in their best financial interest to do so. (p. 7)

These 18 M people relatively healthy people would remain uninsured and would pay a tax that is equal to the lesser of 2.5% of their income (a version of modified AGI) or the average health insurance premium.

Source: All data are from the 2019 column of Table 2 of Foster’s memo. The +4 M is the net of +18.6 M who would enroll in a private plan through an exchange, minus 14.6 M who would no longer fall in the “other private insurance” category, almost all of whom are people who today buy their insurance on the individual market.

(photo credit: Red Barchetta by gumdropgas)

The President’s new stimulus proposal

Was Stuart Varney of Fox Business / Fox News the only one to report the President’s new stimulus proposal?

Here is the President speaking last Friday in the Rose Garden:

We will also build on the measure I signed today with further steps to grow our economy in the future. To that end my economic team is looking at ideas such as additional investments in our aging roads and bridges, incentives to encourage families and businesses to make buildings more energy-efficient, additional tax cuts for businesses to create jobs, additional steps to increase the flow of credit to small businesses, and an aggressive agenda to promote exports and help American manufacturers sell their products around the world.

Leaked from an anonymous White House senior advisor, this would be a trial balloon. When the President reads it from prepared remarks in the Rose Garden on Jobs Day, this is a proposal, no matter what caveats are wrapped around it (e.g., “my economic team is looking at ideas such as …”). He said “We will … build.” That’s definitive. This is an intentional signal, and it’s stunning that almost no one has reported it.

If I have missed coverage, please alert me and I will give appropriate credit.

The President gave a specific list of five items against which he and the Congress will now be measured:

- more highway spending;

- more energy-efficiency incentives;-

- (probably) a new hires tax credit;

- some form of increase in small business loan availability;

- and something unspecified on trade.

Infrastructure spending is sl-o-o-w. I’m surprised there are any energy-efficiency incentives left to be subsidized. I thought they were all maxed out. Greg Mankiw has shown why it’s hard to design an effective and efficient new hires tax credit. I am most interested to see what “aggressive agenda to promote exports and help American manufacturers” they propose. This Administration has been almost silent on trade so far. I hope they don’t treat manufacturers and service firms differently. While it’s good politics, there’s rarely a good economic reason for it.

Why did the President do this? Choose one or more:

- Bad economic news means he thinks he needs to pull hard (again) on the short-term fiscal policy lever.

- Bad economic news means he thinks he needs to look like he’s doing something, even if the actual macro policy impact is trivial.

- Congress has told him privately they’re going to do something more whether he wants it or not, and he’s trying to “get ahead of it.”

The above package looks like the result of a combination of the second and third explanations. It’s reminiscent of when gasoline spikes and everyone scrambles looking for short-term solutions. Don’t just stand there, do something, they argue.

The President’s proposal for stimulus #3, launched upon the signing of stimulus #2, gives Congress a green light. The Democratic majority will have to decide whether to offset the deficit increase of these policies. Someone will probably argue that fiscal stimulus precludes offsetting the deficit impact, but since fiscal stimulus is mostly a timing exercise, you can cut other spending (or raise taxes) in the out years and make the proposal stimulative in the near term and deficit-neutral over time. What, I wonder, will happen to the majority’s claimed adherence to PAYGO rules?

In the abstract, the above package is unlikely to have a noticeable short-run macroeconomic benefit. I think it’s likely to be even less effective and more inefficient than the first stimulus. Will Congressional R’s try to fix this package, or propose their own and unite in opposition to this one?

With the unemployment rate above 10%, near-zero interest rates, enormous budget deficits, and the low-hanging stimulus fruit already plucked, there are few good options. This could get a bit ugly.

(photo credit: karmablue)

Dr. Krugman telegraphs the Left’s long-term fiscal strategy

In Monday’s New York Times, columnist and Nobel laureate Dr. Paul Krugman telegraphs the Left’s long-term fiscal strategy when he writes about California Republicans.

For what we may be seeing is America starting to be Californiafied. … And if Tea Party Republicans do win big next year, what has already happened in California could happen at the national level. In California, the G.O.P. has essentially shrunk down to a rump party with no interest in actually governing … but that rump remains big enough to prevent anyone else from dealing with the state’s fiscal crisis. If this happens to America as a whole, as it all too easily could, the country could become effectively ungovernable in the midst of an ongoing economic disaster.

The strategy is simple:

- Increase government spending, especially through rapidly growing entitlements. At the state level it’s Medicaid.

- Wait. While you’re waiting, define deficits as the problem, rather than spending.

- Try to label as radical and extreme those who argue for slowing spending growth and preventing tax increases. The goal is to discredit these solutions as legitimate.

- Once deficits get large enough, shrug and say we have no choice but to raise taxes. This is especially true for entitlement programs directed toward the elderly, who have less ability to adjust to changed government promises.

- Argue we must protect low and middle-income from higher taxes, so upper-income taxpayers must bear the entire burden increase.

- Raise taxes on upper-income taxpayers.

- Rinse and repeat.

This is a simplified version of an Engorge the Beast strategy, which is almost the converse of the Starve the Beast strategy developed about 20 years ago by some on the Right.

When Dr. Krugman writes “no interest in actually governing … prevent anyone else from dealing with the state’s fiscal crisis,” he means “no interest in raising taxes … prevent anyone else from raising taxes …”

Sure the tea partiers are rauc0us, and the California Republicans are an embittered minority. Yes, there are some offensive fringe nuts at Tea Party rallies. Both parties have their paranoid nutcases and bigots. Dr. Krugman tries to use a few signs to discredit a reasonable position on fiscal policy. I would dismiss this as amateurish if the Times didn’t give him such a big megaphone.

California and the Federal government have another quite reasonable option available. Cut spending. Indeed, just slowing unsustainable spending growth would be a great start. California needs to do this with Medicaid, the Feds need to do it with Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, as well as with the new health care entitlement Congress is trying to create.

This is why I try to encourage elected officials to use the phrase “spending discipline” rather than “fiscal discipline.” Our long-term deficit problem is a spending problem.

New readers of this blog may find these related past posts helpful:

- A short history of higher taxes

- The total tax battle

- America’s long run fiscal problem is spending growth, not taxes

(photo credit: 106177 by El Bibliomata)

The legislative landscape for health care after House passage

The House passed their version of health care reform Saturday night on a 220-215 vote. Today I’m going to update my projections and analysis, and focus on upcoming “pivot points” in the health care debate.

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the House and through the regular Senate process with 60, leading to a law this year; (was 50% -> 40%)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the House and through the reconciliation process with 51 Senate Democrats, leading to a law this year; (was 10% -> 20%)

- Fall back to a much more limited bill that becomes law this year; (was 10% -> 20%)

- No bill becomes law this year Congress. Process continues into next year. (was 29.99% -> 20%)

I have adjusted the scenarios based on two assumptions, making the new numbers not precisely comparable with the old:

- I assume the Finance Committee bipartisan solution path is dead (I only had it at 0.01% chance last time); and

- I assume virtually no chance of a signed law this year, so I have adapted the timeframes accordingly. I say this despite recent statements from the President and Leader Reid that they want/intend to get a law by 31 December.

Pivot points and the importance of recess

Pivot points (my term) are opportunities for legislative momentum to shift. These opportunities are to some extent predictable. This past week had four pivot points, which is extraordinary:

- Election Day – loss of momentum for Ds;

- the Senate Democratic Policy Lunch on Tuesday – loss of momentum for Ds;

- Friday’s politically challenging employment report – loss of momentum for Ds; and

- Saturday night’s House passage vote – momentum gain for Ds.

Sometimes a pivot point will pass without any noticeable change in the legislative outlook. But to the extent these dates/events are predictable, it at least tells you when to look for important shifts.

Here are obvious pivot points over the next few months:

- every Tuesday after the Senate Democratic Policy Lunch;

- whenever CBO releases its score of the Reid substitute amendment;

- the Monday/Tuesday after Thanksgiving recess;

- Friday, December 4th, when the next jobs report is released;

- Th/F December 17-18, the end of the week before the Christmas recess;

- the first week Members are back in DC after the holiday recess;

- late January, for the President’s State of the Union Address.

The most potentially significant consequence of the slower schedule is that Members will be home for two long recesses before a bill might be completed. Will Members feel the same intensity of pressure they did in August? If so, that could greatly shift momentum.

Will Leader Reid begin Senate floor consideration before Thanksgiving recess? If he does, then he will probably have to show his amendment to the world before that recess, and expose his Members to pressure on specific text over that short break. If he waits until after recess, his Members may have a slightly less painful Thanksgiving break, but at the expense of lost time on the backend and a lower probability of Senate passage before Christmas. I would expect him to try to “back up” final passage before the Christmas recess, by in effect telling the Senate around December 18th “you can go home for Christmas only after we’ve finished the bill.” The smell of jet fumes is usually enough to cause Members to vote aye on cloture to shut off a filibuster, but in this case I’m not so sure.

The three-part strategic question

In December Democratic leaders may face a two-part strategic question:

- If we cannot hold 60 Ds, do we use reconciliation to pass a bill with 51, or instead go for 60 on a much more limited bill?

- When do we make this decision?

- Conference or ping pong?

My survey of (Republican) insiders is split on what Democrats may decide on (1), but nearly unanimous on question (2) almost all say this strategic shift would come in January at the earliest. The earliest projection was December 18th.

I assume liberals would prefer a reconciliation path that would probably produce a bill closer to the House-passed bill, at the price of painfully splitting off moderate Senate Democrats. This is a slash-and-burn partisan path, but may be the highest probability path to a signed law. I also assume moderate Democrats would prefer a scaled-back bill. We know Democratic moderates would support the Finance Committee reported bill, so if Senate liberals could swallow hard and wait for the next step, this would be the easiest path to Senate passage. Leader Reid tacked away from this when he announced his amendment would contain a strong public option.

If the Senate can pass a bill, Democratic leaders will need to wrestle with question (3).

Conference or ping pong?

Everyone knew the House would eventually pass something, given the enormous Democratic margin in the House. House Republicans were more effective in their resistance than I anticipated. This contributes to an apparent loss of momentum in the Senate. There are now two games ahead: Senate passage, and reconciling differences between the House and Senate.

In theory, if the Senate passes a bill, the chance of a law skyrockets. But the House passed its bill with a left-edge coalition – most of the Democratic no votes were from moderates. If the Senate passes a bill through regular order (with 60 votes), it will be relatively more moderate, and more compatible with an alliance on the other side of Pelosi’s caucus. This could be quiet difficult. How do Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid work out differences between a bill that Lieberman, Nelson, and Lincoln support and one opposed by moderate House Ds? Splitting the difference may alienate both sides of the Democratic caucuses. We’re already starting to see lines drawn in the sand on abortion.

This is why some observers think Senate passage may lead to ping pong rather than a conference. Normally after the House and Senate pass versions of a bill, the body that votes second requests a conference with the other body and appoints a handful of members to be conferees. The second body then agrees to a conference and appoints its own conferees. The conferees negotiate and produce pretty much whatever new text they want, although they generally stay within the scope of the contents of the two bills. The conference report language must then be passed by both bodies to go to the President.

Ping pong is a colloquial term for skipping conference. The House-passed bill will soon arrive in the Senate. The Senate will presumably take up the House bill and amend it. If and when the Senate passes its version, it would not request a conference, and would not appoint conferees, but would instead send the amended bill back to the House. the House could then try to further amend the Senate bill, or just take it up and pass it. This ping pong can go back and forth a few times.

Conventional wisdom seems to be that House and Senate Democratic leaders are intensely focused on the downsides of a conference. It puts tremendous pressure on the leaders and conferees to resolve differences. It also gives House and Senate Republicans certain procedural opportunities to cause mischief before and during conference.

But ping pong has its own downsides. The minority, especially in the Senate, gets another crack at amending the bill. Smart money would bet today on ping pong rather than a conference, but I expect this to be revisited often over the next couple of months.

My projections

It is highly likely the legislative process will continue at least into January.

I am projecting a 60% chance that a comprehensive bill becomes law this Congress, but I have shifted some of that 60% from the regular order path to the reconciliation path. By itself I’d never expect the Senate to shift to a reconciliation path after failing to get 60 – Senate-only logic says heck no, and the strain on Reid’s caucus would be too great. But if Democratic leaders are forced to shift away from regular order on a comprehensive bill, I would guess that Speaker Pelosi would push hard for the Senate to use reconciliation to produce a bill more compatible with the House-passed bill rather than dialing back expectations. This puts me at 40% regular order success, 20% reconciliation success, 20% fall back to a narrower bill, and a 20% chance the whole thing implodes. It’s the slow pace and the two intervening recesses that give me hope.

Insiders: Please send me your thoughts privately, especially if you disagree.

(photo credit: Matt Tanguay-Carel)

RNC Chair makes the wrong argument on Medicare

Here’s RNC Chairman Michael Steele this morning on ABC News’ This Week with George Stephanopolous.

And the reality — the reality still remains — the reality still remains that, at the end of the day, this thing grows the size of government; it inserts the government between the doctor and the patient. It now requires mandates on states that can’t afford, and it cuts $500 billion from a Medicare program that everyone in this country knows is on the road to bankruptcy.

Chairman Steele and Congressional Republicans are predictably using every policy and political weapon at their disposal to try to stop a bad health care bill. This argument, however, is nonsensical.

Medicare is “on the road to bankruptcy” because its spending is growing too fast. The way to get Medicare off the road to bankruptcy is to slow the growth of (in political parlance, “cut”) Medicare spending. “Cutting” $500 billion of future Medicare spending will make Medicare more fiscally sustainable, not less.

Indeed, we need to slow future Medicare and Medicaid spending by far more than the amounts done by the House or Senate health care bills.

I am not, however, praising the House or Senate bills health care bills for being fiscally responsible. Quite the opposite, since these bills capture so-called Medicare “savings” and then turn around and spend all of it on a new unsustainable health spending entitlement. The resultant policies would be less sustainable than current law, because the politically easy savings from Medicare would be replaced by politically harder-to-cut health insurance subsidies. This is why a vote for these bills is a vote for a future middle-class tax increase, which becomes a much more (politically) likely answer to future entitlement spending problems after the relatively easy Medicare savings have been captured and spent.

Anticipating the commenters, yes a downside of current budgeting rules is that it allows you to move money from one unsustainable program to another and claim that you’re not hurting anything. Technically, you’re not increasing the deficit relative to what it would have been under current law, but it’s irresponsible to increase spending if that current law path is unsustainable.

Had Mr. Steele wanted to play shameless scare-the-seniors politics, he could have accurately said that these bills were taking resources dedicated to seniors and instead spending them on working people. I wouldn’t have liked that argument, but at least it would have been accurate.

I hope Mr. Steele refrains from using this language in the future, or at a minimum modifies his attack so that it’s substantively valid. And shame on the House for yesterday moving us one step closer to fiscal oblivion.

My updated legislative projections for health care reform are coming soon.

(photo credit: Wikipedia)

Finger pointing for fun and profit

I posted yesterday about Budget Director Peter Orszag’s claim of inherited deficits from his Tuesday speech at NYU, titled “Rescue, Recovery, and Reining in the Deficit.” Today I want to look at the rest of Director Orszag’s remarks.

Let’s dive in.

ORSZAG: This is the responsibility that each subsequent generation of Americans must live up to … to build upon the legacy we have inherited and create an economy that is strong, vibrant, and able to sustain our nation long into the future.

Yet here is what CBO said about the President’s budget in March:

CBO: As estimated by CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation, the President’s proposals would add $4.8 trillion to the baseline deficits over the 2010-2019 period. … The cumulative deficit from 2010 to 2019 under the President’s proposals would total $9.3 trillion, compared with a cumulative deficit of $4.4 trillion projected under the current-law assumptions embodied in CBO’s baseline. Debt held by the public would rise, from 41 percent of GDP in 2008 to 57 percent in 2009 and then to 82 percent of GDP by 2019 (compared with 56 percent of GDP in that year under baseline assumptions).

A debt-to-GDP ratio of 82% is not “able to sustain our nation long into the future,” especially when it comes in the midst of the demographic bulge driving increasing entitlement expenditures.

ORSZAG: Almost a year ago, in the fourth quarter of 2008, real GDP was declining at a rate of more than 6 percent per year. In that quarter alone, household net worth fell by almost $5 trillion, dropping at a rate of 30 percent a year.

In terms of employment, the fourth quarter saw a loss of 1.7 million jobs … the largest quarterly decline since the end of World War II and a number only to be exceeded by the next quarter when 2.1 million jobs were lost.

This slowdown in economic activity created a pair of trillion-dollar deficits. One was the budget deficit, which had ballooned to $1.3 trillion for last year even before President Obama first walked into the Oval Office. The other was the deficit between what the economy could produce and what it was producing. This so-called output gap amounted to about 7 percent of the economy.

I have no quarrel with this. In fact, I like it, because it correctly focuses on Q4 of 2008. Those who refer to the “recession which began in Q4 2007” are failing to distinguish between the gently declining economy of Q4 07 – Q3 08 and the plummet in Q4 2008 – Q1 2009 induced by the financial shocks.

ORSZAG: To a degree that we had not experienced in more than half a century, we needed to bring the economy back from the brink.

The first step was to restore confidence in the financial system.

We initiated several programs to stabilize the nation’s financial institutions.

I am happy to report that the sense of crisis in our financial markets seems to have passed, and we now are therefore reshaping our efforts to target assistance to the twin challenges of helping responsible families keep their homes and giving small businesses get easier access to credit.

I am assuming by “we” he means “the Obama Administration.” This is one component of the Big Lie – the claim that the financial sector was in collapse on January 20, 2009, and the actions of the Obama Administration prevented that collapse.

Reality: The programs that stabilized our nation’s financial institutions and prevented a systemic financial collapse were:

- TARP;

- Treasury’s temporary guarantee of Money Market Mutual Funds;

- the expanded FDIC guarantees;

- the Federal Reserve’s new liquidity facilities;

- international coordination before, during, and after the November G-20 Summit hosted by President Bush in Washington; and

- firm-specific agreements (“bailouts”) for Bear Stearns, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, AIG, Citigroup, GM, Chrysler, GMAC, and Chrysler Financial. (Have I left any out?)

All were designed and implemented before January 20th, 2009, during the Bush Administration, with one exception: some of the Fed liquidity facilities were designed and implementation began during December and January, but they were not turned the first few weeks of President Obama’s term.

The above actions were what “pulled the financial system back from the brink of collapse.” The financial rescue occurred on President Bush’s watch. The financial rebuilding and economic recovery are occurring on President Obama’s watch.

In President Obama’s defense, he publicly supported TARP in September 2008 as a Senator. But for his Administration to claim the financial system was on the brink of collapse when he took office is inaccurate, as is saying they “initiated” programs to “stabilize the nation’s financial institutions.” By January 20th, the patient had been moved from the operating room into an intensive care recovery room. The institutions had been stabilized but were still very weak.

The Obama Administration deserves credit (along with the Federal Reserve) for the stress tests and for continued implementation of the liquidity facilities. These were, however, recovery and rebuilding measures, not collapse prevention measures. (Some argue the stress tests were bad and exacerbated moral hazard. I think they were a net positive but am open to the debate.)

Dr. Orszag has his timing wrong. I used to think this was accidental. I have been forced to conclude that it is part of a broader storyline from Obama Administration officials that intentionally mischaracterizes recent history to assign political blame and credit.

Team Obama’s storyline is “Bush screwed it up; we came in and fixed it.” On the financial sector the actual history is one of remarkable continuity, as politically inconvenient as this may be for the current Administration. This should not be surprising when you look at the personnel involved:

- During 2008 and the first three weeks of 2009, the core team developing and implementing rescue policies was Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, and NY Fed President Tim Geithner. I was NEC Director at the time and played a supporting role.

- Beginning January 20th, the core team developing financial recovery and rebuilding policy has been Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, and NEC Director Larry Summers. I distinguish between financial rebuilding and economic rebuilding. The latter includes stimulus and Director Orszag as a key player.

- So 2/3 of the core financial policy team is unchanged from last year, although one player has switched chairs.

The other major financial sector initiative from the Obama Administration was the PPIP, or Public-Private Investment Partnership, which Secretary Geithner announced with much fanfare in March, long before it was ready. Remember when PPIP was the Obama Administration’s answer to how to do TARP better than those Bush Administration foul-ups? PPIP has now faded almost to nothingness. Aside from the stress tests, the core TARP capital purchase program now in place is essentially a continuation of that designed and implemented in the Bush Administration. The same is true for most of the other financial sector rescue and recovery policies.

It conflicts with Team Obama’s preferred storyline, but the actual policy story of financial sector rescue, recovery, and rebuilding is one of remarkable continuity across two Administrations.

ORSZAG: Beyond boosting confidence and stabilizing financial markets, the second step was to bolster macroeconomic demand – jumpstarting economic activity and breaking a potentially vicious recessionary cycle.

In light of the massive GDP gap that we faced, the Administration worked with Congress to enact the Recovery Act just 28 days after taking office. That’s much more rapid and bold action than “the inside lag” economists typically attribute to government policymakers.

I have no problem with the logic, and they deserve credit for reducing inside lag to a minimum. Note that the 2009 stimulus law was partisan, while in 2008 the Bush Administration enacted a bipartisan (and smaller) stimulus bill in a month. Compare the bitter partisan debate over the 2009 stimulus with the 2008 stimulus, negotiated by Secretary Paulson, Speaker Pelosi, and Leader Boehner.

The debate will continue to rage over whether the 2009 stimulus was effective and efficient. My primary complaint is with the inefficiency and poor timing, while others (e.g., JD Foster) question the efficacy as well. The “outside lag” on the 2009 stimulus is terrible.

ORSZAG: Over the past eight months, the Recovery Act has made a difference. Estimates suggest that the bill added three to four percentage points to economic activity in the third quarter.

Last week, we learned that the third quarter real GDP growth was 3.5 percent. In other words, effectively all the growth in real GDP during the third quarter could be attributable – either directly or indirectly – to the Recovery Act.

This is another line the Administration pitches repeatedly – that all good economic news should be attributed to a single policy, the stimulus. This is impossible to prove (or disprove) conclusively.

I think Director Orszag’s qualitative logic is correct here, but believe the Administration severely overstates their case. I think instead:

- The severe decline in the real economy in Q4 2008 and Q1 2009 was almost entirely the result of fallout from the financial crisis.

- The Bush Administration + Bernanke + NYFRB President Geithner prevented systemic financial failure and the collapse of the largest financial institutions.

- Once the financial crisis was averted, the primary economic threat was gone. The poisonous stinger had been removed, and now a long and painful but natural healing process had to take place that will eventually lead to economic recovery, GDP growth, and job and wage growth.

- The Bernanke/Geithner/Summers team largely continued the Paulson/Bernanke/Geithner financial policies which prevented collapse. The new team correctly focused on recovery and rebuilding.

- The new team did a good job (I think) with the stress tests, which resulted in banks raising private capital.

- The liquidity facilities (designed during Bush) provided support to damaged securitization markets and large institutions dependent on dried up short-term liquidity.

- Removed threat of financial collapse + financial rebuilding + near-zero Fed Funds rates -> natural healing eventually.

- The stimulus helped beginning in late Q2 or early Q3 2009. Cash-for-clunkers produced a one-time surge in auto demand (which probably sucked demand forward in time and may have weakened Q4 and Q1 auto demand.)

- The +3.5% Q3 GDP number is unquestionably good news. We hope it will continue but are unsure that it will given weak labor markets that are still getting weaker.

- While the stimulus and cash-for-clunkers undoubtedly contributed to Q3’s GDP number, and will contribute in future quarters, it is a dramatic overstatement to attribute all good economic news to the one element of policy that is most hotly debated.

ORSZAG: Unfortunately, even as the economy begins to turn around, the employment picture isn’t going to brighten immediately … as the contrast between the recently reported GDP numbers and the unemployment numbers that we are expecting later this week will likely illustrate.

The sad fact is that unemployment lags a general recovery, and as the President has said, the coming months will continue to be difficult ones for American workers.

The typical progression in a recovery is first an increase in productivity; then an increase in hours worked; and finally, the hiring of additional workers by firms.

I have no argument with the above. It again provokes the above question – when that job growth does occur, I assume the Administration will claim that one policy is responsible for all of it.

It’s important to remember that Presidents get both more credit and more blame for the health of the economy than they deserve. Tomorrow’s monthly employment report will be significant economically and politically. At the same time, it’s quite difficult to affect the tidal forces of the business cycle with fiscal policy, and I don’t “blame” the slow job growth on the Administration. They’re doing the best they can, and I didn’t like the stimulus, but I think their primary macroeconomic failure has been one of poor communications and expectations management. They overpromised on stimulus, and they have tried to take basically bad economic news and frame it as good news. Those are not policy mistakes, they are communications mistakes.

ORSZAG: Although the month-to-month change in aggregate hours worked has not yet turned consistently positive, its decline has moderated from the depths of last fall and winter.

In other words, the employment picture is still getting worse each month. I won’t repeat this point, which I have made ad nauseam.

It also demonstrates how sloppy the Administration’s rhetoric has been this year (but not here). See this LA Times article for many examples of conflicting promises and language. Whatever your views of the Bush Administration’s policies, we were never this sloppy with language. I know – I spent thousands of hours fact-checking and proofreading speeches and documents to be released. Then again, we were held to a higher standard by the press.

ORSZAG: The results were not a surprise, but they were still sobering: the deficit for last fiscal year was $1.4 trillion, or 10 percent of our economy.

Next year’s deficit is expected to be about the same size, and current projections show $9 trillion in deficits over the next 10 years, averaging about 5 percent of GDP.

Deficits of this size are serious – and ultimately unsustainable.

I strongly agree. Most economists I know would say anything sustained above 3% of GDP is unsustainable. When pressed, most would say they dislike but can live with deficits in the 1-2% of GDP range indefinitely, because GDP growth prevents the debt/GDP ratio from increasing. Somewhere between 2 and 3% of GDP seems to be the breakpoint – I use 2.5% as a rule of thumb for the maximum that, while highly undesirable, can be sustained without serious long-term economic damage. I think of this number as a rough ceiling, above which danger lurks.

Since I covered it yesterday, I will skip Director Orszag’s argument about inherited deficits, other than to note that while his speech is titled “… and Reining in Deficits,” he does not actually explain how the Administration would rein in deficits.

ORSZAG: Over the long-term, deficits tend to have some combination of two effects. First, they can raise interest rates and decrease investment, as the federal government goes into the credit markets and competes with private investors for limited capital.

Second, deficits can increase the amount that the United States borrows from abroad, as foreigners step in to finance our consumption.

Either way … whether deficits increase interest rates or borrowing from abroad … the long-term effect is the same: It generates a greater burden on you … our future workers.

If interest rates rise and investment falls, that will make you less productive and reduce your incomes. And, if we borrow more from abroad as a result of our deficits, that means that more of your future incomes will be mortgaged to pay back foreign creditors.

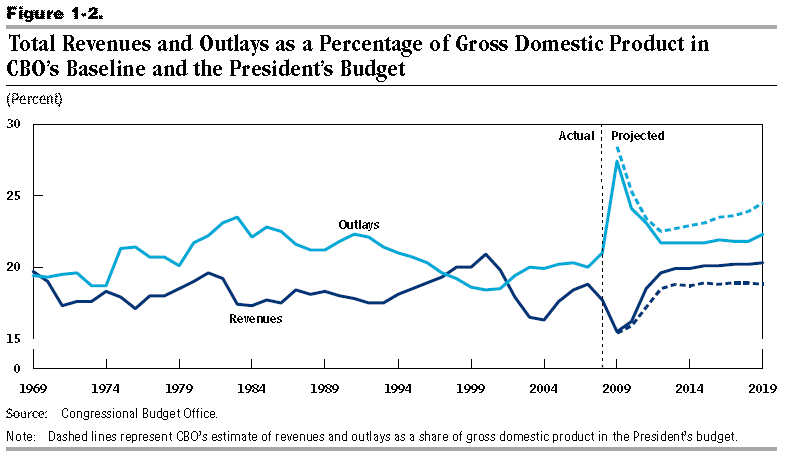

I agree. Why then would you produce a budget that CBO says looks like this, in which you make the, deficit, the gap between projected spending and projected revenues bigger?

Note also that CBO says the President’s budget shifts a flat revenue line down, while it bends the spending curve upward. It’s the increase in the slope of the dotted light blue spending line that is scary. The President’s budget would keep revenues near their post-WWII average of just above 18% of GDP. It’s spending that explodes.

ORSZAG: While we are addressing our short-term economic crisis with deficit spending, as we must, we also are taking on the biggest threat to our long-term fiscal future: rising health care costs.

Our fiscal future is so dominated by health care that if we can slow the rate of cost growth by just 15 basis points per year (that is, 0.15 percentage points per year), the savings on Medicare and Medicaid would equal the impact from eliminating Social Security’s entire 75-year shortfall.

This is another red herring. The reality is:

- Our long-term deficit problem is driven entirely by the growth of spending.

- More specifically, it is driven by the growth of three programs: Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

- The spending growth in these programs is driven by three factors:

- demographics – we’re living longer, and the Baby Boomers are now retiring;

- the Social Security benefit formula grows more generous as our economy grows; and

- Medicare and Medicaid spending grow as per capita health spending grows.

- Director Orszag talks about (3) to the exclusion of (1) and (2), and he focuses on the wrong timeframe.

- Director Orszag’s own graph shows that demographics is a bigger problem than health care costs for the next 30-40 years.

- He’s right that health care cost growth is more significant after that, but we’ll never make it that far on our current path. As Butch Cassidy said to the Sundance Kid who was afraid of jumping from the cliff into the river because he couldn’t swim, “Are you crazy? The fall will probably kill you.” (h/t Andrew Biggs)

ORSZAG: Right now, we are further along toward our goal of fiscally responsible health reform than ever before. I believe that in the weeks to come, the President will sign a bill that gives those with health insurance stability and expands coverage, and does so while boosting quality and reducing long-term deficits.

Let me be clear: any bill that the President will sign will not add to the deficit over the next decade and will reduce deficits thereafter.

Not good enough. “Reducing deficits thereafter” is inadequate. We need fundamental structural reductions in future federal health spending growth to prevent our budget (and the US economy) from collapsing. Trivial amounts of deficit reduction are insufficient to address our long-term federal health spending problem.

The pending health care legislation makes our health spending problem worse than under current law, increases health entitlement spending, and trivially reduces future deficits only by increasing taxes even more than the net spending increases. We should take the Medicare savings proposed in the pending legislation, reconfigure it to save more from fee-for-service Medicare and less from Medicare Advantage plans, and capture those budgetary savings to begin to address our long-term entitlement spending problem. You don’t solve a spending problem by creating a $1+ trillion new spending program.

ORSZAG: This will be done through a “belt and suspenders” approach. That is, we are relying on hard, accountable savings – as scored by the independent Congressional Budget Office – to pay for health reform and we are not banking for that purpose on the potentially much more important cost-savings that will come from transforming the health care delivery system.

In this way, the worst-case scenario is that we have reformed health care and paid for it. But because we’re also taking substantial steps to make health care more efficient over the long term, reform will also undoubtedly help to improve our long-term fiscal standing … even if it is challenging to quantify by precisely how much.

Translation: CBO says these bills would trivially reduce the deficit, leaving our long-term fiscal problems essentially unchanged. He says “we are not banking for that purpose on potentially much more important cost-savings,” but the reality is that Director Orszag cannot convince CBO, his own staff, or the Administration’s official actuaries that his so-called game changing transformations would “undoubtedly” slow the growth of federal spending. If any official estimator agreed with this claim, Director Orszag would have publicized those results long ago.

Director Orszag (and the President) argue that providing people with better information alone will change behavior and reduce utilization of medical care. But information is insufficient … people also need financial incentives to change their behavior, and those incentives are absent from the proposed legislation. Director Orszag tried to steer CBO in this direction when he ran it. As soon as he left, CBO’s career staff steered CBO back to the consensus view.

ORSZAG: Once health reform is passed, however: the job of getting our nation back on a fiscally sustainable course will not be complete. Our current projections of 4 to 5 percent of GDP in budget deficits in the out-years are well above the fiscally sustainable level of roughly 3 percent.

To bring deficits down to a sustainable range, therefore, will require more action once the economy is into a recovery. We are currently considering a number of proposals to put our country back on firm fiscal footing, and to cut the deficit we inherited in half by the end of the President’s first term.

Watch out. I would wager that “more action” and “a number of proposals” are code either for tax increases or a bipartisan commission to provide cover for tax increases. The size of the problem is so large that I don’t see how they can actually solve it without massive reductions in spending growth or middle-class tax increases. The numbers don’t work if you just tax “the rich.”

These statements are also an implicit acknowledgement that the President’s Budget, proposed earlier this year, is insufficient to address our long-term fiscal problems. Why are they waiting until after the new $1+ trillion entitlement is enacted to argue we need to tighten our belts? Deficit reduction would be easier if they began by not spending $1+ trillion more. Then they could use the offsets from the pending health bills for deficit reduction instead.

Also note “cut the deficit we inherited in half by the end of the President’s term.” OMB’s Mid-Session Review shows a 2009 deficit of $1.58 T (11.2% of GDP), and the President proposes to reduce that in FY 2013 to $775 B (4.6% of GDP).

And yet:

- 4.6% of GDP is clearly unsustainable; and

- CBO says the President’s budget would instead increase the FY 2013 deficit by $373 B;

- it’s absurd to measure “cut in half” compared to the year in which there was a one-time deficit spike from the $700B TARP.

ORSZAG: And, after years of failing to abide by the simple principle that you should pay for what you spend, the Administration has proposed statutory “pay-as-you-go,” or, as it’s often called, “PAYGO” legislation. PAYGO would require that any new tax cut or entitlement program be fully paid for – just as we are doing today with health reform.

In the 1990s, PAYGO’s commonsense approach encouraged the tough choices that helped transform large deficits into surpluses … and its absence over the past eight years accounts for the $5 trillion figure that I mentioned earlier.

The Administration claims to abide by PAYGO, but exempts $200+ B to increase Medicare spending on doctors, the $787 B stimulus, and the new $100B – $200B we’re-not-calling-it-a-second-stimulus bill being prepared on the Hill right now. I covered this yesterday in more detail.

ORSZAG: After all, it took us years to dig ourselves into the current fiscal hole. And, it will take years for us to get out.

But I … along with the President and the rest of the Administration … all are committed to making our way … responsibly and rapidly … out of this fiscal hole.

I conclude with the apocryphal First Rule of Holes: When you’re in one, stop digging.

The inherited deficits fallacy

Budget Director Peter Orszag spoke at NYU yesterday, a speech titled “Rescue, Recovery, and Reining in the Deficit.”

I wrote a super-long post yesterday, but it was too much. So today I respond to the headline-inducing element of the speech. Tomorrow I will post a longer point-by-point response to the rest of his speech.

Warning: my tone in this post is a smidge more aggressive than usual. Director Orszag’s speech fired me up.

Here is the part of the Director’s speech that got the most attention:

ORSZAG: So how did we get here?

Of the $9 trillion in deficits projected over the coming decade, nearly $5 trillion comes as a result of failing to pay in the past for just two policies – the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts and the creation of a Medicare prescription drug benefit.

The cost of the tax cuts will total about $4 trillion over the next decade, including the additional interest on the debt the federal government will have to pay since the tax cuts were deficit financed. The Medicare prescription drug bill will add about another $700 billion to the deficit – bringing us to about $5 trillion total for the cost of just these two policies.

In addition, roughly $3.5 trillion can be attributed to automatic economic stabilizers.

As the economy enters recession, certain spending programs, such as unemployment insurance and food stamps, automatically increase and revenues tend to decline. Although this helps to ameliorate the economic downturn by stimulating demand, it also leads to higher deficits.

Finally, there is the Recovery Act which accounts for just 10 percent of the entire deficit over the next decade.

All told, the entire $9 trillion deficit reflects the failure to pay for policies in the past and the cost of the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression and the steps we had to take to combat it.

Now, assigning blame never solves a problem, but it is important to understand that we didn’t get where we are merely as a result of bad luck.

It was the result of decisions – conscious, but unfortunate – and it will take deliberate action for us to work our way out of this situation.

And it’s critically important that we do just that.

Let’s break it into pieces.

ORSZAG: Of the $9 trillion in deficits projected over the coming decade, …

This is Director Orszag’s made-up number. CBO says the baseline deficits over the next decade are half as large, $4.5 trillion.

ORSZAG: … nearly $5 trillion comes as a result of failing to pay in the past for just two policies … the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts and the creation of a Medicare prescription drug benefit.

The cost of the tax cuts will total about $4 trillion over the next decade, including the additional interest on the debt the federal government will have to pay since the tax cuts were deficit financed. The Medicare prescription drug bill will add about another $700 billion to the deficit … bringing us to about $5 trillion total for the cost of just these two policies.

Director Orszag is correct that neither the Medicare drug benefit nor the tax cuts were offset with other spending cuts or tax increases. He fails to tell you that in 2003 Congressional Democrats wanted to spend more on Medicare drugs than the bill President Bush signed into law. (President Obama was a State Senator at the time.) He fails to tell you that President Obama did not propose means-testing the drug benefit to save money, as President Bush tried to do. He also fails to tell you that President Obama’s budget proposes to continue $3.2 trillion of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts and the AMT patches that followed them. (See the first few lines of Table S-5.) He also fails to tell you that his $9 T figure includes $835 B for the stimulus and associated interest costs that President Obama clearly did not inherit.

While he wants to argue that these “$5 trillion” are “not his fault,” the same could be said about all federal spending and taxes in place when President Obama took office. Had Medicare not been enacted in 1965 or had Social Security benefits not been indexed to wages rather than inflation in the 70s, our budget would be in surplus today (if nothing else had changed). It is misleading to attribute future deficits to any particular past policy change, as future deficits are the result of a calculation assuming unchanged extensions of all past policy changes into a path for total future spending and total future tax receipts. Director Orszag is picking and choosing particular policies to try to assign blame. How much of future deficits are because future Medicare spending was not offset when Medicare was enacted in 1965?

This is closely related to the PAYGO myth the Administration is trying to popularize. The core of the Administration’s budget message is: “Our predecessors were irresponsible by not paying for their policy changes. They left us a mess. We are being responsible by paying for everything we do.”

The reality is more complex. The two parties have different visions of PAYGO, and both parties violate their visions on occasion.

- Republicans, including President Bush, generally try to offset proposed mandatory spending increases with spending cuts. I support almost every spending cut and almost every tax cut in front of me, and support packaging them together when I can but don’t sacrifice one for the absence of the other.

- This was violated for the Medicare drug benefit. You can blame this on President Bush, or on the Republican-majority House of the late 90s that first passed an unpaid-for universally subsidized Medicare drug benefit, or on the Congressional Democrats who proposed to spend even more without offsets. I would note that President Bush developed a proposal to package the Medicare drug benefit with dramatic changes to restructure fee-for-service Medicare and make it compete with private health plans on a level playing field. This proposal would have more than offset the increased spending from the drug benefit. House Republican Leaders (in 2003) rejected these reforms and insisted on just doing the drug benefit because AARP and Congressional Democrats opposed the reforms.

- Moderate Democrats (to the extent they exist in Washington) argue mandatory spending increases and tax cuts should be offset. They (and Republicans) ignore discretionary spending increases.

- The Obama Administration and Congressional Democrats invoke PAYGO when it’s convenient and ignores it when it’s inconvenient:

- The Administration did not insist that the stimulus be offset (they could have insisted on deficit reduction far in the future to preserve the short-term stimulus effect). Even now Director Orszag hides those deficit increases in the baseline and excludes them from his calculations of the deficit impact of President Obama’s policies.

- The Administration buried $200+ B of proposed Medicare spending increases on doctors in the baseline and worked with Leader Reid to try to pass these as a standalone bill without offsets.

- Congressional Democrats are now drafting a $100B – $200B we’re-not-calling-it-a-second-stimulus bill to extend certain provisions of the first. My sources tell me this bill will not be offset.

- The reality is that each party has a view of what should and should not be “paid for,” and each violates it when it’s the only way to get high priority legislation through Congress.

ORSZAG: In addition, roughly $3.5 trillion can be attributed to automatic economic stabilizers.

As the economy enters recession, certain spending programs, such as unemployment insurance and food stamps, automatically increase and revenues tend to decline. Although this helps to ameliorate the economic downturn by stimulating demand, it also leads to higher deficits.

I can’t find this number. I think he’s summing up recent past and near-future revenue losses and spending because our economy is operating below “potential.” My view is, so what? All Presidents have to deal with economic fluctuations, sometimes severe ones. You shouldn’t time your deficit reduction to hit when you’re trying to promote short-term economic growth, but a deficit is a deficit and accumulated debt doesn’t know what its source was. Try to make them smaller whatever their cause. This really has the feel of “IT’S NOT MY FAULT!”

ORSZAG: Finally, there is the Recovery Act which accounts for just 10 percent of the entire deficit over the next decade.

… only if you start from Director Orszag’s made-up $9 trillion baseline deficit number. If you start from CBO’s $4.5 T baseline, and if you include interest costs as he does for the tax cuts he didn’t like, you’re above 20%.

ORSZAG: All told, the entire $9 trillion deficit reflects the failure to pay for policies in the past and the cost of the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression and the steps we had to take to combat it.

This is brazen. Translation: $9 trillion of deficits over the next ten years are not our fault.

I have three problems with this:

- The number is made up. CBO says it’s half as big.

- You support continuations of most of the policy changes you attack.

- You will be in office for (at least) the next four years and can do something about it.

- Your policies would make the problem you describe worse. CBO says much worse.

Here is the math behind the Administration’s claim of fiscal responsibility, and CBO’s countervailing analysis. All figures are for the next ten years (2010-2019):

|

Administration |

CBO |

|

| Additional debt under the baseline |

$9.0 trillion |

$4.5 trillion |

| Additional debt under the President’s budget |

$7.0 trillion |

$9.3 trillion |

| Effect of the President’s budget on additional debt |

-$2.0 trillion of debt |

+$4.8 trillion of debt |

I wrote about this extensively in March: Baseline games.

ORSZAG: Now, assigning blame never solves a problem, but it is important to understand that we didn’t get where we are merely as a result of bad luck.

It was the result of decisions – conscious, but unfortunate – and it will take deliberate action for us to work our way out of this situation.

In early January CBO estimated a deficit for FY 2009 of 8.3% of GDP. Most of that was because of the TARP. That 8.3% is a genuinely “inherited” problem that is not President Obama’s “fault.” Since January, economic deterioration and policy changes enacted into law by the Obama Administration and the Congress put the FY 2009 deficit at 10% of GDP. I don’t know whose fault that additional 1.7% is, but it is the responsibility of the current leadership.

Similarly, CBO projected that at the end of FY 2009 debt as a share of GDP would slightly exceed 50%. CBO projected that, under baseline policies, debt/GDP would climb to 56% by 2019. The 50% was inherited and not Team Obama’s “fault.” The 56% is unfortunate, but you’re elected to change policy, so fix it if it bugs you. How, then, does the Administration explain the proposed increase of debt/GDP to 82% of GDP?

Director Orszag tries to redefine the baseline so that his inherited future deficit and debt problem look worse, and his boss’ culpability for future deficits and debt looks smaller. I disagree with his budget mechanics, but so what? Ever since Medicare and Medicaid were created in the 1960s and Social Security’s indexing formula was changed in the 1970s, every President has inherited a future deficit problem. Each year that problem goes unsolved, the problem gets harder to fix. President Obama is no different. Complaining about future problems but not proposing solutions just looks whiny.

Suck it up. Each President has the ability to propose changes and fix the problem. Director Orszag focuses on the deficit-increasing policies of the Bush Administration, but ignores the President’s attempt to slow the growth of Social Security spending, his proposed Medicare reforms, or the Medicaid savings the Obama Administration undid in the stimulus bill earlier this year. He ignores President Bush’s veto of an out-of-control farm bill (passed in a Republican-majority Congress), his attempt to restrain obscene Congressional highway spending desires, and his unpopular but principled vetoes of two S-CHIP bills because they spent $12 B too much. Think about that: in late 2007 and early 2008 we were fighting about $12 B of spending.

If you think the Medicare drug benefit was a mistake, then propose changes to it. Means-test it rather than turning off the Medicare funding warning trigger as the House did earlier this year. If you don’t like the future deficit impacts of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, then don’t propose to continue most of them, or propose other tax increases to pay for them. That’s why you’re in office: to change policies with which you disagree. It’s absurd to complain about future deficits that you have the ability to

It’s even more absurd when the policies you propose make the problem worse. Director Orszag’s argument is belied once again by the Congressional Budget Office, which wrote in March:

CBO: As estimated by CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation, the President’s proposals would add $4.8 trillion to the baseline deficits over the 2010-2019 period. … The cumulative deficit from 2010 to 2019 under the President’s proposals would total $9.3 trillion, compared with a cumulative deficit of $4.4 trillion projected under the current-law assumptions embodied in CBO’s baseline. Debt held by the public would rise, from 41 percent of GDP in 2008 to 57 percent in 2009 and then to 82 percent of GDP by 2019 (compared with 56 percent of GDP in that year under baseline assumptions).

The most disappointing aspect of Director Orszag’s speech is not the details of his substantive argument. It’s that he would use a valuable and limited resource, his ability to command attention and shape the policy agenda, to assign blame rather than propose solutions. We need the current Administration to spend less time worrying about whether future problems are their fault, and more time trying to solve those problems.

You inherited debt/GDP of 50.5%. Under your policies that will increase to 82%. Please stop worrying about whose fault that is and do something about it. Propose a solution.

(photo credit: Center for American Progress)

How to turn your kids into lifelong tax cutters

My former White House colleague Tevi Troy suggested the following method for turning children into lifelong tax cutters.

- Make each of your kids spread his or her Halloween candy out on the kitchen table.

- Take one-third of it.

- Say, “That’s called taxes.”

- Repeat each Halloween.

I figure it will take maybe two years of this to turn them into lifelong tax cutters.

For most kids, this is probably the first income they have earned through their own labor. Maybe it’s better they learn about taxes now, rather than 10-15 years from now when they first ask “Who the h*** is FICA?”

You might see a cheating dynamic in future years, in which your Halloween taxpayers try to hide some of their income from the taxman.

If anyone actually tries this:

- You are an evil parent.

- Please report your kids’ reactions so we can all learn from them.

Tevi promises he has not done this to his kids.

(photo credit: Halloween Candy by aus_chick)