Legislative hostage taking

Former Senator Phil Gramm (R-TX) famously said, in his trademark Texas drawl,

Never take a hostage you’re not willing to shoot.

I heard him say this to a Republican colleague who had blocked a Clinton Administration nominee as leverage on an unrelated policy issue. The White House publicly confronted the hostage-taking Senator, who promptly folded. Gramm knew that, if you were going to make a legislative threat to block a bill or nominee, you needed to be willing to actually carry through with your threat (“shoot the hostage”). The other guy might call your bluff, and you needed to be willing to accept both responsibility for the policy damage caused by your action, as well as the associated political pain. And once you’re seen as an empty bluffer, your future threats have no power.

It appears that Senate Budget Committee Chairman may be making this mistake. The Washington Post reports,

Conrad is the leader of a group of Senate moderates threatening to block an increase in the debt limit unless Congress also votes to create a bipartisan task force on deficit reduction with broad powers to force tax increases or spending cuts through Congress.

If this report is accurate, then Senator Conrad is bluffing. If Leader Reid calls his bluff, neither Senator Conrad nor his colleagues will block an increase in the debt limit. Nor should they.

Having worked on too many debt limit increases to count, from both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue, I will claim the following are six rules of debt limit increase legislation:

- Treasury always says the debt limit must be increased by a certain date, and usually claims that date is a hard backstop, implying that the USG will default if the limit is not increased by that date.

- Treasury always has more cash management tricks it can use to push that hard date just a smidge farther.

- Some Senator almost always foolishly threatens to hold the debt limit increase bill, usually in an atttempt to gain leverage on some unrelated issue.

- At the end of the day, that hostage-taker always folds, and a clean debt limit increase passes. It is sometimes part of a larger bill, but the threat to block it always goes away if the demand is too great.

- The majority party has the responsibility for delivering the needed 51 votes to pass the bill. The minority gets a free ride, although sometimes the leaders will work together.

- Therefore, the debt limit increase always passes, although sometimes a few days late, forcing Treasury to dip into its bag of tricks. And the U.S. Government never defaults on Treasuries.

These are not the rules you’d like to govern the process. They’re ugly and messy. In an ideal world, Treasury wouldn’t have to dip into its bag of cash management tricks, each of which has increasingly harmful policy consequences, to buy a little more time for Congress to act.

But the end result has always been success, and I see little prospect for changing the process, so I’ll just try to explain it.

There is a fairly predictable dance that occurs each time the government approaches the statutory limit on debt held by the public:

<

ul>

- [Majority Leader] “Mr. President, I ask unanimous consent that the Senate proceed to and have a roll call vote on the House-passed debt limit bill.”

- [Hostage-Taking Senator] “Mr. President, reserving the right to object, I ask the Leader’s request be modified to allow a vote on my [unrelated] amendment to the debt limit increase bill, or to allow a vote on my [unrelated] issue as a separate freestanding bill.”

- [Majority Leader] “I object to your modification. There will be no amendments to this bill, and I cannot commit to a vote on your issue as a freestanding bill.”

- Now the hostage-taker has to decide if he wants to be the one to kill a clean debt limit increase bill by objecting to the Leader’s unanimous consent request. Sure, he can try to blame it on the Majority Leader, but he’ll lose that battle in the press.

- The hostage-taking Senator then backs down, and the Majority Leader’s UC is agreed to.

- The Senate votes and passes the bill. Members of the majority party know they have the responsibility to pass the bill. Those up for reelection may ask the Leader if they can vote no, but no member of the majority will outright refuse to vote aye on this vote if the Leader insists. Sometimes the Majority Leader will ask the Minority Leader for help delivering votes, and depending on the state of their relationship at that moment, he may get help.

- But it always passes. Always.

There’s a simple legislative logic that gives the Majority Leader leverage against Hostage-Taking Senator when they offer competing UCs. It is politically difficult to defend killing or blocking a bill because of something that is not in the bill. After all, you’ll have other opportunities to pursue your goal, so you don’t need to get your vote to add your provision right now, on this bill. In contrast, this is a must-pass bill, and if you block it, you are responsible for the U.S. government defaulting on its debt. No Member of Congress, no matter how extreme, is willing to take the blame for that. The rhetorical, political, and therefore actual leverage goes to he who is arguing for this must-pass bill to be “clean.”

It is, however, possible to block a debt limit increase in favor of a smaller debt limit increase (within reason on the amounts). Then neither Senator has rhetorical leverage in the battling UC’s, because both want a clean increase in the debt limit. In fact, often the power shifts to whoever wants a smaller increase, because it’s hard to argue against “You can come back and extend it again later.”

Chairman Conrad may get his commission, although I doubt it he will get it now. He may get his vote, although I doubt as an amendment to a clean debt limit bill. If he confronts Leader Reid over the debt limit, either in private or on the Senate floor, Reid has all the leverage. He can force Conrad to back down.

While I wish the process were cleaner and more straightforward, I am quite comfortable with this relative imbalance of power. Nobody should mess with the full faith and credit of the U.S. government for any reason. When there is an increasing focus on the U.S. deficit and the credit rating of the U.S. government, this only reinforces the importance of reassuring the world that the U.S. government honors its debts no matter what. There are plenty of other legislative tools available to generate procedural leverage on other important policy issues. I am glad that most Senators are smart enough and savvy enough to leave the debt limit alone.

(photo credit: Dodging Bullets by hao$)

How would the Reid bill affect the middle class?

There has been confused public discussion about the effects of the Reid bill on low- and middle-income taxpayers. Senator Grassley and his Finance Committee staff have worked with the Joint Tax Committee staff to disentangle the strands a present and clearer picture of the actual financial effects of the Reid bill on different middle class populations.

Grassley’s staff summarize the results this way:

First, there is a group of low- and middle-income taxpayers who clearly benefit under the bill. This group, however, is relatively small. There is another much larger group of middle-income taxpayers who are seeing their taxes go up due to one or a combination of the following tax increases: (1) the high cost plan tax, (2) the medical expense deduction limitation, and (3) the medicare payroll tax. In general, this group is not benefiting from the tax credit (because they are not eligible for the tax credit), but they are subject to the tax increase(s). Also, there is an additional group of taxpayers who would be affected by other tax increase provisions that JCT could not distribute. Finance Committee staff is working with JCT to determine how to identify this “un-distributed” group of people. … This analysis reveals that while a relatively small group of middle-class individuals, families, and single parents are benefiting under the Reid bill, a much larger group of middle-class individuals, families, and single parents are disadvantaged.

Senate Democrats have used a different JCT analysis that show the combined effects on these two populations when blended together. You have a relatively small group of people getting big net benefits, and a much larger group paying net costs. The aggregate impact for the two populations combined is a net benefit for the group as a whole, and advocates for the bill have therefore argued the bill is a “middle class tax cut.” Senator Grassley and his staff deserve credit for separating the effects on distinct (and large) subpopulations.

Here’s the quantitative summary for the Reid bill. All figures are for the year 2019, and in each case these are net results of premium changes, tax subsidies, and tax increases.

- 17.8 million individuals, families, and single parents with incomes under $200K will be net financial winners (11% of all tax returns under $200K):

- Of that 17.8 million total, 13.2 million of them will benefit from the government subsidy for health insurance, net of any premium increases.

- The other 4.6 million of them will also benefit, netting out their premium reduction with the higher taxes they will pay. These people in general will not get a health insurance subsidy.

- 68.4 million individuals, families, and single parents with incomes under $200K will be net financial losers (41% of all tax returns under $200K):

- In general these people are not eligible for premium subsidies, so the effects of he Reid bill on them are direct premium effects and/or tax increases.

- Within this group, here are some representative averages, taking into account premium changes, tax subsidies for premium purchase, and tax increases:

- Within this population of 68.4 million net losers, an average individual working for a small business who gets health insurance through the small group market will be worse off, even if his income is below $10K per year:

- Income of 0 – $10K: He pays $31 more (per year).

- Income of $10K – $20K: He pays $99 more.

- Income of $20K – $30K: He pays $202 more.

- Income of $30K – $40K: He pays $325 more.

- Income of $40K – $50K: He pays $377 more.

- Income of $50K – $75K: He pays $576 more.

- Income of $75K – $100K: He pays $681 more.

- Income of $100K – $200K: He pays $726 more.

- If this individual works for a large employer buying insurance in the large group market, the bill helps him if his income is <$20K, and hurts him if his income is >$20K:

- Income of 0 – $10K: He pays $135 less.

- Income of $10K – $20K: He pays $67 less.

- Income of $20K – $30K: He pays $36 more.

- Income of $30K – $40K: He pays $159 more.

- Income of $40K – $50K: He pays $211 more.

- Income of $50K – $75K: He pays $410 more.

- Income of $75K – $100K: He pays $515 more.

- Income of $100K – $200K: He pays $561 more.

- For an average family among the 68.4 million losers getting insurance through the small group market (including most small business employees), they are on average better off if their family income is <$20K, and worse off if their income is >$20K. If they get insurance through a large employer, the breakpoint is $30K.

- For an average single parent among the 68.4 million losers, he or she will be better off if income is <$20K, and worse off if income is >$20K, whether he or she gets insurance in the small group or large group markets.

- Within this population of 68.4 million net losers, an average individual working for a small business who gets health insurance through the small group market will be worse off, even if his income is below $10K per year:

While the press obsesses over the public option and abortion, will they pay sufficient attention to the harder-to-explain components of the bill that would make 68.4 million middle-class individuals, families, and single parents worse off?

Lots more detail is below and linked, courtesy of Senator Grassley and his fine staff.

From Senate Finance Committee Republican staff

Here is an analysis of the premium changes, tax subsidies, and tax increases under the Reid bill. Here are the JCT tables that were the basis for these findings: 4 tax provisions in 2019, tax credits in 2019, and universe of returns in 2019. The other data source is the November 30th CBO letter to Senator Bayh.

Based on this analysis, Finance Committee staff believes we can summarize the benefits and disadvantages to individuals, families, and single parents under the Reid bill this way: First, there is a group of low- and middle-income taxpayers who clearly benefit under the bill. This group, however, is relatively small. There is another much larger group of middle-income taxpayers who are seeing their taxes go up due to one or a combination of the following tax increases: (1) the high cost plan tax, (2) the medical expense deduction limitation, and (3) the medicare payroll tax. In general, this group is not benefiting from the tax credit (because they are not eligible for the tax credit), but they are subject to the tax increase(s). Also, there is an additional group of taxpayers who would be affected by other tax increase provisions that JCT could not distribute. Finance Committee staff is working with JCT to determine how to identify this “un-distributed” group of people.

Further Analysis Reveals Benefits and Disadvantages to

Individuals, Families, and Single Parents

Analysis of Premium Changes, Tax Subsidies, and Tax Increases

On November 30, 2009, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated the average premiums for single and family health insurance policies purchased in the non-group market and offered by small businesses and large employers under both the Reid bill and current law. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) has provided Finance Committee Republican staff with a distributional analysis of four of the major tax provisions in the Reid bill, along with a distributional analysis of the number of tax returns that will receive the premium tax credit for health insurance for 2019. Based on this data, Finance Committee Republican staff compared the average premium change, according to CBO, with the average subsidy or tax increase individuals, families, and single parents would see, based on JCT data in 2019, and concluded following:

- According to JCT, 13.2 million individuals, families, and single parents or 8% of all tax returns under $200,000 in 2019 will benefit from receiving the government subsidy for health insurance, net of any health insurance premium increases under the Reid bill.

- According to JCT, a group of 4.6 million individuals, families, and single parents or 3% of all returns under $200,000 in 2019 will also benefit from a premium reduction, net of a tax increase, under the Reid bill. In general, this group of 4.6 million individuals, families, and single parents are NOT eligible to receive the subsidy for health insurance.

- According to JCT, a group of 68.4 million individuals, families, and single parents or 41% of all returns under $200,000 in 2019, however, will be worse off as a result of a tax increase, net of any premium reduction, under the Reid bill. In general, this group of 68.4 million individuals and families are NOT eligible to receive the subsidy for health insurance.

- An average individual who receives health insurance through a small employer and earning between $0 and $200,000 would be paying, on average, a range of $31 to $726 more. In the large group market, an average individual making between $20,000 and $200,000 would be paying, on average, a range of $36 to $561 more.

- An average family who receives health insurance through a small employer and earning between $20,000 and $200,000 would be paying, on average, a range of $82 to $892 more. In the large group market, an average family making between $30,000 and $200,000 would be paying, on average, a range of $116 to $724 more.

- An average head of household who receives health insurance through a small employer and earning between $20,000 and $200,000 would be paying, on average, a range of $383 to $1,587 more. In the large group market, an average head of household also making between $20,000 and $200,000 would be paying, on average, a range of $185 to $1,419 more.

This analysis reveals that while a relatively small group of middle-class individuals, families, and single parents are benefiting under the Reid bill, a much larger group of middle-class individuals, families, and single parents are disadvantaged.

Background

Premium Analysis – CBO has estimated the average premiums in 2016 for a single and family health insurance policy in (1) the non-group, (2) the small group, and (3) the large group health insurance markets under both the Reid bill and current law. Based on CBO data, we can identify the average annual increase in premiums in each of these markets under the Reid bill and current law. Based on these CBO’s estimates and data, we can project the cost of a single and family health insurance policy in (1) the non-group, (2) the small group, and (3) the large group markets under the Reid bill and current law in 2019.

Tax Increase and Subsidy Analysis – JCT has provided Finance Committee staff with a distributional analysis of four of the major tax provisions in the Reid bill – (1) the advance-refundable tax credit for health insurance, (2) the high cost plan tax, (3) the medical expense deduction limitation, and (4) additional Medicare payroll tax. Separately, JCT has provided a distributional analysis of the number of tax returns that will receive the premium tax credit for health insurance. Based on this data, we can determine how many individuals, families, and single parents receive the premium tax credit for health insurance. We can also identify (1) those individuals, families, and single parents who are NOT eligible to receive the tax credit and (2) those individuals, families, and single parents whose taxes may go up before they see some type of tax reduction from the tax credit.

Eligibility for the Subsidy for Health Insurance – Under the Reid bill, individuals, families, and single parents between 133% and 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) who purchase health insurance through the “exchange” would be eligible for a subsidy for health insurance. In general, individuals, families, and single parents who get health insurance through their employer are NOT eligible for the subsidy, even if they are below 400% of FPL.

Analysis

Comparison of Subsidy for Health Insurance and Premium Increase

Based on the projected cost of an average single and family health insurance policy in the non-group market in 2016, and based on CBO data on the average premium inflation rates under the Reid bill and current law, Finance Committee Republican staff projected the average cost for these plans in the non-group market in 2019. Staff then compared the premium changes with the average subsidy for health insurance an individual, family, or single parent would receive based on JCT data. The below tables illustrate this comparison.

As we can see from the below tables, every individual, family, or single parent is benefiting irrespective of a premium increase.

Non-Group – Single

| Income | Premiums Under Reid Bill | Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Increase | Subsidy | Net Premium Increase/Premium Subsidy |

| $0 to $10,000 | $6,953 | $6,444 | $509 | ($6,500) | ($6,218) |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $6,953 | $6,444 | $509 | ($5,694) | ($5,412) |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $6,953 | $6,444 | $509 | ($4,723) | ($4,441) |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $6,953 | $6,444 | $509 | ($3,742) | ($3,459) |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $6,953 | $6,444 | $509 | ($4,075) | ($3,793) |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $6,953 | $6,444 | $509 | ($3,304) | ($3,022) |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $6,953 | $6,444 | $509 | ($667) | ($384) |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $6,953 | $6,444 | $509 | ($1,500) | ($1,218) |

Non-Group – Family

| Income | Premiums Under Reid Bill | Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Increase | Subsidy | Net Premium Increase/Premium Subsidy |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($9,183) | ($5,544) |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($14,127) | ($10,489) |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($14,647) | ($11,008) |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($14,129) | ($10,490) |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($13,542) | ($9,904) |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($11,117) | ($7,478) |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($6,743) | ($3,110)) |

Non-Group – Head of Household

| Income | Premiums Under Reid Bill | Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Increase | Subsidy | Net Premium Increase/Premium Subsidy |

| $0 to $10,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($7,555) | ($3,916) |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($7,958) | ($4,139) |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($7,464) | ($3,825) |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($7,764) | ($4,125) |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($9,201) | ($5,562) |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($9,497) | ($5,858) |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($8,039) | ($4,400) |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $19,026 | $15,387 | $3,639 | ($8,500) | ($4,861) |

Comparison of Premium Reduction and Tax Increase

Based on the projected cost of an average single and family health insurance policy in the small group and large group market in 2016, and based on CBO data on the average premium inflation rates under the Reid bill and current law, Finance Committee Republican staff projected the average cost for these plans in the small and large group markets in 2019. Staff then compared the premium changes with the average tax increase an individual or family would see based on JCT data. The below tables illustrate this comparison.

As we can see from the below tables, low-income individuals, families, and single parents between $0 and $20,000 (and in the case of a family policy in the large group market, between $0 and $30,000) are benefiting from the premium reduction, net of a tax increase. Individuals, families, and single parents with income between $20,000 and $200,000, however, are actually paying more, net of the premium reduction and tax increase.

Small Group – Single

| Income | Premiums Under Reid Bill | Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Reduction | Subsidy | Tax Increase | Net Tax Increase/Premium Reduction |

| $0 to $10,000 | $9,130 | $9,130 | $0 | $0 | $31 | $31 |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $9,130 | $9,130 | $0 | $0 | $99 | $99 |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $9,130 | $9,130 | $0 | $0 | $202 | $202 |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $9,130 | $9,130 | $0 | $0 | $325 | $325 |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $9,130 | $9,130 | $0 | $0 | $377 | $377 |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $9,130 | $9,130 | $0 | $0 | $576 | $576 |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $9,130 | $9,130 | $0 | $0 | $681 | $681 |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $9,130 | $9,130 | $0 | $0 | $726 | $726 |

Small Group – Family

| Income | Premiums Under Reid Bill | Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Reduction | Subsidy | Tax Increase | Net Tax Increase/Premium Reduction |

| $0 to $10,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $88 | ($80) |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $99 | ($69) |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $250 | $82 |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $452 | $284 |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $620 | $452 |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $743 | $575 |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $826 | $658 |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $1,060 | $892 |

Small Group – Head of Household

| Income | Premiums Under Reid Bill | Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Reduction | Subsidy | Tax Increase | Net Tax Increase/Premium Reduction |

| $0 to $10,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $0 | ($168) |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $55 | ($113) |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $521 | $353 |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $1,294 | $1,126 |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $1,755 | $1,587 |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $1,482 | $1,314 |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $1,114 | $946 |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $22,469 | $22,637 | ($168) | $0 | $999 | $831 |

Large Group – Single

| Income | Premiums Under Reid Bill | Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Reduction | Subsidy | Tax Increase | Net Tax Increase/Premium Reduction |

| $0 to $10,000 | $8,514 | $8,680 | ($166) | $0 | $31 | ($135) |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $8,514 | $8,680 | ($166) | $0 | $99 | ($67) |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $8,514 | $8,680 | ($166) | $0 | $202 | $36 |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $8,514 | $8,680 | ($166) | $0 | $325 | $159 |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $8,514 | $8,680 | ($166) | $0 | $377 | $211 |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $8,514 | $8,680 | ($166) | $0 | $576 | $410 |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $8,514 | $8,680 | ($166) | $0 | $681 | $515 |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $8,514 | $8,680 | ($166) | $0 | $726 | $561 |

Large Group – Family

| Income | Average Premiums Under Reid Bill | Average Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Reduction | Subsidy | Tax Increase | Net Tax Increase/Premium Reduction |

| $0 to $10,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $88 | ($248) |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $99 | ($237) |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $250 | ($86) |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $452 | $116 |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $620 | $284 |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $743 | $407 |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $826 | $490 |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $1,060 | $724 |

Large Group – Head of Household

| Income | Average Premiums Under Reid Bill | Average Premiums Under Current Law | Premiums Reduction | Subsidy | Tax Increase | Net Tax Increase/Premium Reduction |

| $0 to $10,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $0 | ($336) |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $55 | ($281) |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $521 | $185 |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $1,294 | $958 |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $1,755 | $1,419 |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $1,482 | $1,146 |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $1,114 | $778 |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $23,542 | $23,878 | ($336) | $0 | $999 | $663 |

(photo credit: White House official photo by Sharon Farmer)

The President’s new economic proposal

Here is the President’s new economic proposal, which he is not calling a stimulus:

I. Accelerating near-term job growth

<

ol>

<

ul>

- “More money for infrastructure: highways, transit, rail, aviation, and water.” The explicit listing in significant in the legislative process. In the fact sheet they also emphasize broadband networks.

- “Support for merit-based infrastructure investment that leverages federal dollars.” I don’t know what this means in practice.

- “Rebates for consumers who make energy efficiency retrofits” [to their homes].

- Expanding those energy efficiency and clean energy manufacturing programs “for which additional federal dollars will leverage private investment and create jobs quickly, such as industrial energy efficiency investments and tax incentives for investing in renewable manufacturing facilities in the U.S.”

II. TARP & Fiscal discipline

- [Claiming to] redirect TARP savings “to work on Main Street” – This is a gimmick. “The … steps the President took to stabilize the financial system have reduced the cost of TARP by more than $200 billion, providing additional resources for job creation and for deficit reduction.”

- “Exploring a range of steps to take as part of the FY2011 budget process.”

III. Long-term job creation

- Extending unemployment insurance.

- Extending the COBRA health insurance subsidy.

- Providing another $250 payment to seniors and veterans.

- More funds transferred to state and local governments.

Analysis

This package seems driven largely by Members of Congress trying to satisfy their political need to be seen as doing something while the economy and job growth are weak. It is trying to work on two levels:

- It’s trying to stimulate macro demand through traditional deficit-increasing fiscal stimulus measures: infrastructure and clean energy spending, plus all the transfer payments. In this respect it roughly parallels February’s stimulus law.

- It’s trying to increase the supply of capital and labor, but to small businesses only, through the hiring tax credit, zero cap gains, and depreciation incentives.

I think policymakers will struggle most with the hiring tax credit. We looked at it a couple times during the Bush Administration and could not find a version with more benefits than costs. How much is a temporary reduction in compensation costs going to encourage a small business owner to hire an employee? In my simplistic view, expected future demand for a firm’s products is far more important. On a macro level, job growth follows GDP growth, and it anticipates future GDP growth. Thus, if you want near-term job growth, figure out how to increase GDP growth. It’s difficult for government to quickly increase the number of people hired, holding the future path of GDP growth roughly constant. The most effective and efficient policy lever for GDP growth and therefore job growth is the Fed Funds rate, but that’s tapped out, so policymakers are struggling to find other levers.

They will also have a problem with churning – you fire me, then immediately rehire me to get the tax credit. To address this, the President proposed a new tax credit to hire and keep employees. This means subsidizing jobs “saved” in addition to those “created.” This tries to address the churning problem but exacerbates the inefficiency problem. I think they will find that most of the tax benefit is inframarginal – they will be subsidizing hires (or keepers) that would have occurred anyway, so the marginal number of new hires resulting from this policy will be small relative to the dollars spent. They will probably get very little bang for the buck. Finally, they will create all sorts of ugly distortions if they limit the incentive to small businesses. This targeting is a politically popular way to keep the budgetary cost down, but I am just as happy if people now unemployed get hired by big firms as by small firms.

This package looks like the President is giving a green light to House allies who are developing their own bill, as long as the bill includes a few of the President’s priorities. I expect the bulk of the money in a final law would be in bucket #3 – the extensions of UI benefits, health insurance subsidies, the senior-pandering checks, and the transfers to state and local governments.

Bucket #1 includes the President’s priorities, and I expect reflects his primary message points over the next month or two: small business, infrastructure, and clean energy. These are easy demands for Congress to fulfill.

Bucket #2 is empty – the President is telling Congress they don’t have to offset the new spending and tax relief with other spending cuts or tax increases. They can claim that TARP repayments reduce the deficit to offset the new proposed deficit increases. That’s a gimmick, but it may work to cloud the deficit question. I expect a $150ish B deficit increase.

Inferring from the speech, prior signals from the White House, and other sources, this announcement looks like the result of the following White House logic:

- Whether we want them to or not, the House is going to pass something that they can argue will help job growth.

- We can either get on board and try to shape it, or get run over by it.

- Let’s try to shape it and take some credit for it.

This logic is not partisan – we (Bush team) were often faced with a similar dilemma.

The primary difficulty for Team Obama will be how they integrate this with their overall economic message. This law will probably make their policy and communications jobs harder, not easier.

Here are some challenges this bill creates for the Obama White House:

- The structure of this package is quite similar to the $787 B stimulus. This makes it hard for Team Obama to argue this is not a second/third/fourth stimulus.

- It therefore undermines their argument that their prior policies are working (or at least sufficient.)

- The bill would increase the deficit a lot (most are guessing around $150 B, a big number) when the policy and political pressure is strong and growing for deficit reduction. (See this article for an example of the policy challenge.)

- The infrastructure spending and grants to states will in all likelihood face the same challenges we have seen all year: they are in general slow, inefficient, and prone to fraud and embarrassing revelations.

Prior to the President’s speech, action on a “jobs bill” was most evident in the House. The Senate is busy with health care, and Leader Reid does not have floor time to devote to this in December. We now have a rough Obama-House Democrat alliance. I expect Senate Democratic leaders will soon come on board, leaving Congressional Republicans with their own challenges:

- They will be politically inclined to oppose it, and have remained remarkably unified in their opposition to the President and Democratic majority’s stimulus proposals so far. But some will like the small business incentives, many will (semi-secretly) like the infrastructure spending and try to get a piece of it, and nearly all will support the transfer payments.

- Some Republicans will want to sign on board and “improve” the package, either for policy or political reasons. Republican leaders will need to decide whether to oppose the package straight up, oppose the package and develop a Republican alternative, or negotiate a compromise with Democratic leaders. I’ll bet they do the second.

- I think they will also focus on the deficit impact and argue that the economic benefits of the President/House Democrats proposal are small, while the deficit impact is large.

My views

This looks like a smaller version of the original stimulus law. Its origins are more political and fulfilling a legislative need, than policy-driven.

- I’m OK with the UI extension and extending the health insurance subsidy, although I wish both were better designed.

- I generally support tax relief, but I am concerned the targeted capital gains reduction will give some cover to let the broader capital tax rates jump at the end of 2010. That would be very bad.

- The spending programs will have little near-term GDP effect, and so should be evaluated in how they meet other policy goals. They’re largely ineffective as immediate stimulus, because government spending is slow.

- The $250 check to seniors was pandering the first time Congress passed it (on a broadly bipartisan vote). It’s still pandering. Why are seniors more deserving of aid than, say, a low-income working family?

- The “using TARP dollars to help Main Street” is a transparent gimmick. If you’re going to increase the deficit, it’s better just to stand up and say the deficit increase is worth the short-term economic benefit you think will result from the other policies.

I suggest they do a targeted bill that contains only the UI and COBRA provisions, because I think the large deficit impact of the other provisions, relative to their small macroeconomic benefit, isn’t worth it.

A good jobs day

Today’s employment report is good news:

- Only 11,000 net jobs were lost in November. Given the margin of error on this data, that’s basically equivalent to zero.

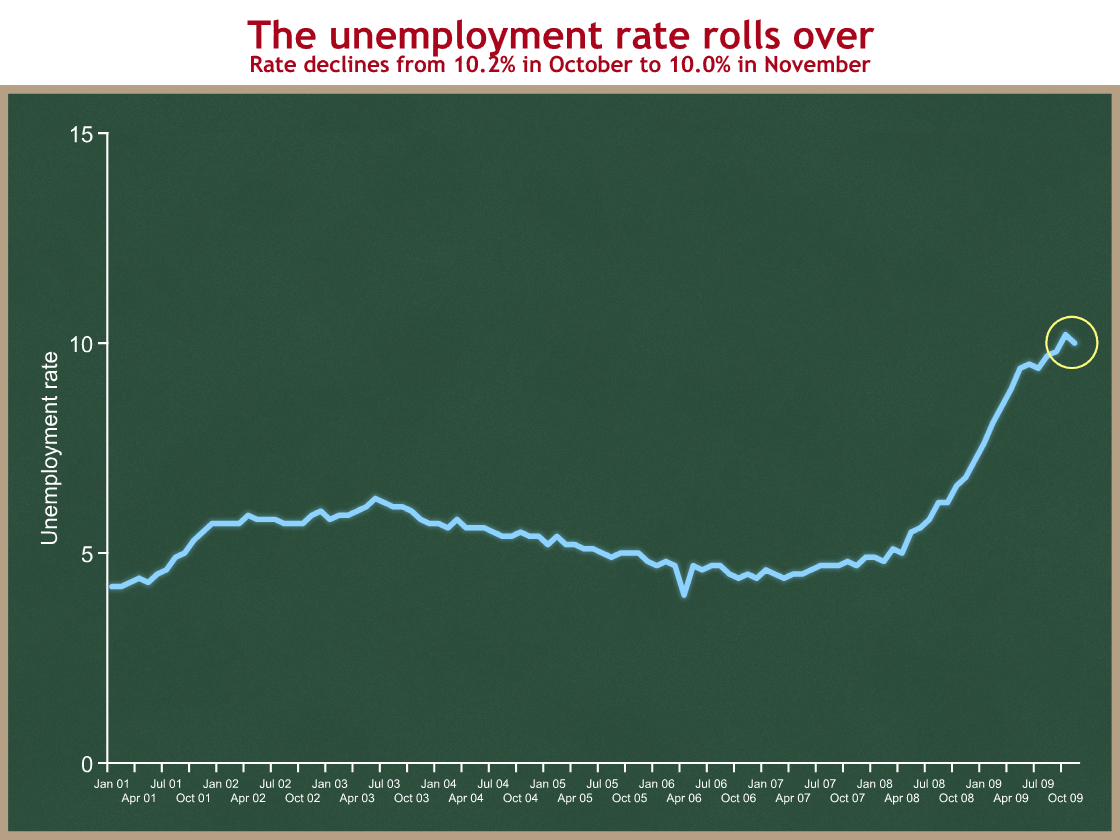

- The unemployment rate declined from 10.2% in October to 10.0% in November.

- Data for September and October were revised upward. The U.S. economy still lost jobs in those months, but fewer than previously estimated.

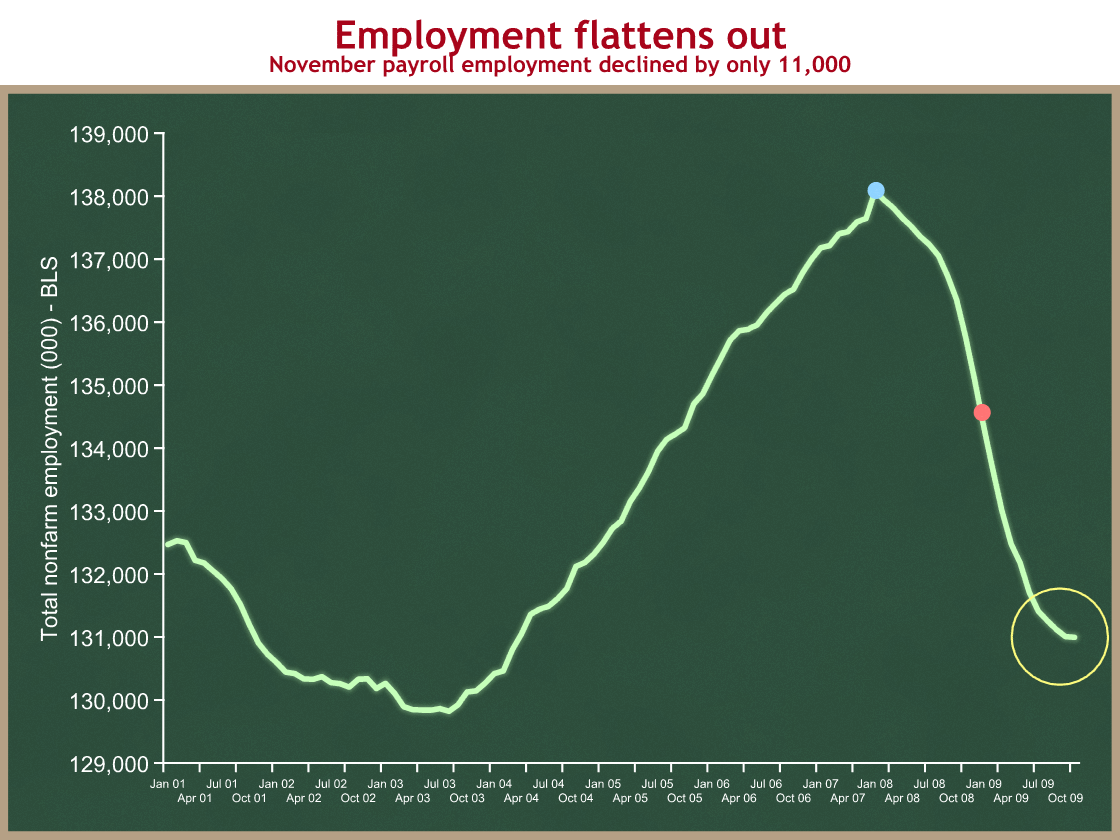

The graph below shows the employment level – the number of people working in the U.S. according to the payroll survey. You can see that the line has flattened out in the past month. That’s a good thing.

At the same time, you can see how much slack there is in the economy. We’re down 7.156 million jobs from the peak in December 2007 (the blue dot), and down 3.337 million jobs since President Obama took office in January 2009 (the red dot).

Here is the graph for the unemployment rate. You can see the rate has turned down over the past month. That, too, is good news.

Regular readers will remember that there are several useful job growth markers. The first is for job growth to begin. We can further subdivide that into two components: first the job decline needs to stop, then job growth needs to begin. It appears the job decline has essentially stopped, although most economists whom I trust will wait for a second month of data to confirm it. Now we need job growth to begin.

After job growth begins, the next marker is when job growth exceeds about 150K jobs per month. That’s a good rule-of-thumb number for when we should expect to begin to see steady declines in the unemployment rate.

The final marker is full employment. We obviously have a long, long way to go before reaching that point. I use 5.0% as my rule-of-thumb for full employment. With today’s workforce of about 154 million people (in the household survey), we’d need to create about 7.7 million jobs starting now to return to full employment. And since the labor force generally grows over time, by the time we get there it’ll probably be around 8 million above today’s levels. That’s a lot of new jobs we need the economy to create.

I’d like to suggest five takeaway points for you:

- Today’s report is good news.

- We should wait for one more month of data to confirm today’s report before concluding that job declines have ended.

- The picture has flattened out, but has not yet turned upward. In political rhetoric, if next month’s data confirms today’s data, we will no longer be “headed in the wrong direction.” We won’t be “headed in the right direction” until the top graph turns up.

- Once job growth has broken zero, the next threshold is +150K jobs per month. That should roughly coincide with a declining unemployment rate.

- We have a longway to go:

- We need the economy to create 3.3 million jobs to get back to the employment level when President Obama took office.

- We need it to create 7.2 million jobs to get back to our previous high in December 2007.

- We need it to create about 8 million jobs to get back to full employment.

The President’s 2010 challenges: jobs, deficits, and taxes

I think health care will dominate the first month or two of the 2010 American domestic policy debate. But by the end of February we will either have a law or the bill will have died.

Jobs, deficits, and taxes will dominate the rest of the 2010 American domestic policy debate:

- The unemployment rate is 10.2%. The Administration projects it will remain in the high 9s throughout 2010, even as it projects real GDP to grow 2 – 3%. (2.0% year-over-year growth, and 2.9% comparing Q4 2009 to Q4 2010).

- The Administration projects a 2010 deficit of 10.4% of GDP, compared to 11.2% this year. They project an average budget deficit for the next ten years of 5.1%, and a 4% deficit at the end of the decade. Those are unsustainably high deficits.

- The Administration projects steadily rising debt held by the public, from 41% of GDP in 2008, to 56% this year, to 66% next year, to 77% by the end of the decade.

- CBO’s projections for deficits and debt are even more pessimistic than the Administration’s.

- Under current law, the Bush tax cuts are scheduled to expire on at the end of 2010. If no new law is enacted, on January 1, 2011 (oversimplifying a bit):

- The individual income tax rates will increase from 10/15/25/28/33/35 to 10/15/28/31/35/39.6%.

- Capital gains rates will increase from 15% to 20%.

- Dividend tax rates will increase from 15% to being taxed as ordinary income.

- The estate tax will return to its pre-2001 state: a $1M exemption and a top rate of 55%.

- The AMT “patch” will again expire, as it does each year after Congress fixes it only one year at a time.

The problem for the President is that there are tensions among these problems.

- Accelerating GDP and job growth requires big fiscal or monetary stimulus. The Fed has the dial set to 11, so fiscal stimulus is all that’s left. As a policy matter, a big new stimulus program would substantially further increase at least the short-term deficit and take at least a few months to even begin to have an impact. As a political matter, the Administration has poorly managed stimulus implementation and communications to the point that even they are afraid of the word “stimulus.” The President’s communications and political advisors are, I imagine, groaning at the thought of the President’s policy answer to slow job growth being another stimulus. Then again, they’re probably also panicked about another year of 9+% unemployment.

- Getting serious about budget deficits requires some combination of big spending cuts and/or big tax increases.

- While Congressional Republicans are almost never able to muster the votes for big spending cuts, at least they’re generally willing to talk about them as the preferred solution. (How’s that for faint praise?) I have seen no indication that the President or any of his allies (except House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer) are willing to significantly slow the growth of spending. To have a measurable effect on the long run spending problem, one has to address demographics and health care cost growth in Medicare and Medicaid. But Director Orszag routinely ignores demographics in his presentations, arguing the long-run problem is only about health care costs. The President and his allies have lowered their long-term fiscal goal for health care reform to only slight improvements in our deficit picture. Even those small improvements are contingent on wildly optimistic assumptions about future Congressional behavior.

- That leaves tax increases. The Administration already has baked into their projections revenue gains from allowing the top rates and capital tax rates to rise. Getting a lot more revenue (measured in percentage points of GDP) requires either returning to pre-Reagan tax rates or a new source of revenue. Q1: Will the President propose a new value-added tax (VAT), which would raise taxes on all consumers and break the President’s pledge? Q2: Will he instead propose a new business activity tax (BAT) which would have similar effects but which he could claim taxes businesses rather than individuals?

- As worried as the President’s Congressional allies might be about the policy and political impacts of dangerous deficits, it’s hard to imagine them preferring to spend election year 2010 pushing for big spending cuts or big tax increases. I imagine they’ll be looking for ways to punt.

- The scheduled automatic tax increases pose another conundrum. On the one hand, they need the revenues to prevent future deficits from being even worse than projected. On the other, if the economy is still soft at the end of 2010, tax increases are counterproductive. And while some on the left may think it’s easy to raise the top two individual tax rates, they forget that there was a broad bipartisan consensus in 2001 and 2003 to lower those top rates. The partisan dispute in 2003 was over cap gains and dividends, not the individual rates. This is largely because the top rates have been politically redefined as small business tax rates. When Congressional Republicans insist on votes throughout 2010 to prevent tax increases on successful small business owners during a time of economic weakness, will moderate and nervous Congressional Democrats want to vote against small business?

Within the White House the budget process is almost certainly driving these decisions. In my experience, most big Presidential budget decisions take place in November and December, to be rolled out in the State of the Union address and the release of the President’s Budget in the first week of February.

Here’s a policy checklist of questions they need to answer:

- Do we propose a new fiscal stimulus? If so, do we offset it in the outyears with spending cuts or tax increases? Or do we (misleadingly) claim we’re using returned TARP dollars to finance it?

- What do we do if we’re not going to propose a new fiscal stimulus, but our Congressional allies charge forward anyway?

- Do we propose a major deficit reduction package in next year’s State of the Union address and President’s Budget? If so, does it include entitlement spending cuts (unlikely), even bigger tax rate increases, or a new revenue source?

- How hard do we push back if moderate and nervous Congressional Democrats want to postpone the tax increases scheduled to take effect at the end of 2010?

Senate floor #011: The “hidden tax” of the uninsured

I have heard the following argument frequently and expect to hear it much more over the next few weeks. Here is Senator Baucus speaking on the Senate floor Monday:

Third, health care reform will work to repeal the hidden tax of more than $1,000 in increased premiums that American families pay each year in order to cover the cost of caring for the uninsured.

I am skeptical about the $1,000 figure, which is from an outside group, but let’s assume it’s accurate.

CBO estimates that the Reid bill would reduce the number of uninsured in 2016 (when the plan is in full effect) from 52 million to 23 million. That’s a 55% reduction in the number of uninsured.

If we’re generous and presume that the so-called “hidden tax” is reduced proportionately, then this indirect premium subsidy would be cut in half, not repealed.

Senator Baucus covered himself by saying “work to repeal” rather than “repeal,” but the impression left with the reader is that the Reid bill would eliminate this cost-shift. Others are not as careful with their language as Senator Baucus is here.

I have written before that I have always been skeptical of the cost shifting argument. Here’s the best response I’ve seen to my skepticism.

Whether or not cost-shifting is real, and whether or not the $1,000 figure is good, the Reid bill would at best cut that figure in half. More importantly, total health spending and costs to the insured will increase if we cover more of the uninsured with taxpayer-subsidized insurance. This sounds almost tautological, but it needs to be said: covering more people costs more money. Yes, there are some indirect savings through less use of emergency and charity care, but those savings are small compared to the gross outlays of subsidizing the purchase of health insurance for many others.

If you’re advocating a policy to subsidize coverage for people who are now uninsured, I hope you’ll argue that the benefits to those uninsured are worth the higher costs to others. Don’t argue that we’ll save money overall, or that it will financially benefit those who are now insured. This one isn’t a free lunch.

Senate floor #010: Minority party rights and tactics

Yesterday Senate Budget Committee Ranking Republican Judd Gregg sent Senate Republicans a reminder of all the procedural tools available to Senators “to insist on a full, complete, and fully informed debate on all measures and issues coming before the Senate.” When you’re in the majority, you often refer to these as stalling tactics and obstructionism. When you’re in the minority trying to prevent a bad bill from becoming law, you often refer to these as rights that can be protected.

I’ll cut and paste the description of the rights. I won’t describe them here – please consider this a reference document.

Since the Senate is now considering the bill and the Reid substitute amendment, we’re past section I. Tools still available and useful to the minority begin with “Senate Points of Order,” the third bullet in section II.

FOUNDATION FOR THE MINORITY PARTY’S RIGHTS IN THE SENATE (Fall 2009)

The Senate rules are designed to give a minority of Senators the right to insist on a full, complete, and fully informed debate on all measures and issues coming before the Senate. This cornerstone of protection can only be abrogated if 60 or more Senators vote to take these rights away from the minority.

I. RIGHTS AVAILABLE TO MINORITY BEFORE MEASURES ARE CONSIDERED ON FLOOR

(These rights are normally waived by Unanimous Consent (UC) when time is short, but any Senator can object to the waiver.)

- New Legislative Day – An adjournment of the Senate, as opposed to a recess, is required to trigger a new legislative day. A new legislative day starts with the morning hour, a 2-hour period with a number of required procedures. During part of the ?morning hour? any Senator may make non-debatable motions to proceed to items on the Senate calendar.

- One Day and Two Day Rules – The 1-day rule requires that measures must lie over one ?legislative day? before they can be considered. All bills have to lie over one day, whether they were introduced by an individual Senator (Rule XIV) or reported by a committee (Rule XVII). The 2-day rule requires that IF a committee chooses to file a written report, that committee report MUST contain a CBO cost estimate, a regulatory impact statement, and detail what changes the measure makes to current law (or provide a statement why any of these cannot be done), and that report must be available at least 2 calendar days before a bill can be considered on the Senate floor. Senators may block a measure’s consideration by raising a point of order if it does not meet one of these requirements.

- “Hard” Quorum Calls – Senate operates on a presumptive quorum of 51 senators and quorum calls are routinely dispensed with by unanimous consent. If UC is not granted to dispose of a routine quorum call, then the roll must continue to be called. If a quorum is not present, the only motions the leadership may make are to adjourn, to recess under a previous order, or time-consuming motions to establish a quorum that include requesting, requiring, and then arresting Senators to compel their presence in the Senate chamber.

II. RIGHTS AVAILABLE TO MINORITY DURING CONSIDERATION OF MEASURES IN SENATE

(Many of these rights are regularly waived by Unanimous Consent.)

- Motions to Proceed to Measures – with the exception of Conference Reports and Budget Resolutions, most such motions are fully debatable and 60 votes for cloture is needed to cut off extended debate.

- Reading of Amendments and Conference Reports in Entirety – In most circumstances, the reading of the full text of amendments may only be dispensed with by unanimous consent. Any Senator may object to dispensing with the reading. If, as is often the case when the Senate begins consideration of a House-passed vehicle, the Majority Leader offers a full-text substitute amendment, the reading of that full-text substitute amendment can only be waived by unanimous consent. A member may only request the reading of a conference report if it is not available in printed form (100 copies available in the Senate chamber).

- Senate Points of Order – A Senator may make a point of order at any point he or she believes that a Senate procedure is being violated, with or without cause. After the presiding officer rules, any Senator who disagrees with such ruling may appeal the ruling of the chair – that appeal is fully debatable. Some points of order, such as those raised on Constitutional grounds, are not ruled on by the presiding officer and the question is put to the Senate, then the point of order itself is fully debatable. The Senate may dispose of a point of order or an appeal by tabling it; however, delay is created by the two roll call votes in connection with each tabling motion (motion to table and motion to reconsider that vote).

- Budget Points of Order – Many legislative proposals (bills, amendments, and conference reports) are subject to a point of order under the Budget Act or budget resolution, most of which can only be waived by 60 votes. If budget points of order lie against a measure, any Senator may raise them, and a measure cannot be passed or disposed of unless the points of order that are raised are waived. (See http://budget.senate.gov/republican/pressarchive/PointsofOrder.pdf )

- Amendment Process

- Amendment Tree Process and/or Filibuster by Amendment – until cloture is invoked, Senators may offer an unlimited number of amendments — germane or non-germane — on any subject. This is the fullest expression of a ?full, complete, and informed? debate on a measure. It has been necessary under past Democrat majorities to use the rules governing the amendment process aggressively to ensure that minority Senators get votes on their amendment as originally written (unchanged by the Majority Democrats.)

- Substitute Amendments – UC is routinely requested to treat substitute amendments as original text for purposes of further amendment, which makes it easier for the majority to offer 2nd degree amendments to gut 1st degree amendments by the minority. The minority could protect their amendments by objecting to such UCs.

- Divisible Amendments – amendments are divisible upon demand by any Senator if they contain two or more parts that can stand independently of one another. This can be used to fight efforts to block the minority from offering all of their amendments, because a single amendment could be drafted, offered at a point when such an amendment is in order, and then divided into multiple component parts for separate consideration and votes. Demanding division of amendments can also be used to extend consideration of a measure. Amendments to strike and insert text cannot be divided.

- Motions to Recommit Bills to Committee With or Without Instructions – A Senator may make a motion to recommit a bill to the committee with or without instructions to the Committee to report it back to the Senate with certain changes or additions. Such instructions are amendable.

- AFTER PASSAGE Going to Conference, Motions to Instruct Conferees, Matters Out of Scope of Conference

- Going to Conference – The Senate must pass 3 separate motions to go to conference: (1) a motion to insist on its amendments or disagree with the House amendments; (2) a motion to request/agree to a conference; and (3) a motion to authorize the Chair to appoint conferees. The Senate routinely does this by UC, but if a Senator objects the Senate must debate each step and all 3 motions may be filibustered (requiring a cloture vote to end debate).

- Motion to Instruct Conferees – Once the Senate adopts the first two motions, Senators may offer an unlimited number of motions to instruct the Senate’s conferees. The motions to instruct are amendable – and divisible upon demand — by Senators if they contain more than one separate and distinct instruction.

- Conference Reports, Out of Scope Motions – In addition to demanding a copy of the conference report to be on every Senator’s desk and raising Budget points of order against it, Senators may also raise a point of order that it contains matter not related to the matters originally submitted to the conference by either chamber. If the Chair sustains the point or order, the provision(s) is stricken from the conference agreement, and the House would then have to approve the measure absent the stricken provision (even if the House had already acted on the conference report). The scope point of order can be waived by 60 Senators.

- Availability of Conference Report Language. The conference report must be publicly available on a website 48 hours in advance prior to the vote on passage.

Senate floor #009: Middle class tax increases

On October 29th, Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Grassley spoke about health care tax increases. At the time he was talking about the Baucus bill, but his comments also apply to the Reid amendment.

According to the official Congressional scorekeepers – the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Congressional Budget Office – the Finance Committee bill contains over a half trillion dollars worth of tax increases, fees, and penalties on individuals and businesses.

The Joint Committee on Taxation – also known as Joint Tax – has testified that a significant percentage of these tax increases, fees, and penalties will be borne by middle class taxpayers. That is, families making $250,000 and singles making $200,000 a year.

Since then, the Senate Finance Committee Republican tax staff have received updated analysis for the Reid amendment. Here’s the staff summary.

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) conducted a distributional analysis of how four tax provisions in the Reid bill – in the aggregate – affected people. The four tax provisions JCT analyzed were the (1) the advance-refundable tax credit for health insurance, (2) the high cost plan tax, (3) the medical expense deduction limitation, and (4) additional Medicare payroll tax.

- In 2019 – when the bill is in full effect – JCT’s distributional analysis shows that, on average, individuals making over $50,000 and families making over $75,000 would see their taxes go up under the Reid bill. In other words, out of those taxpayers affected by these four tax provisions, 42 million “middle class”families and individuals – those earning less than $200,000 – on average, would pay higher taxes under Majority Leader Reid’s amendment.

- Again, this is after taking into account the tax effects of the advance-refundable tax credit for health insurance.

Millions of more middle class families and individuals could bear a tax increase from the health care industry “fees” proposed under the Reid bill.

- Although JCT has not provided a distributional analysis of the effect of the “fees,” JCT and the Congressional Budget Office have testified to the Senate Finance Committee that these “fees” (1) would be passed through to health care consumers and (2) would increase health insurance premiums and prices for health care-related products. This means that any person with health insurance – either purchased from an insurance company or provided to workers through a self-insured arrangement – will see their premiums go up. In addition, any person purchasing or accessing a medical device (e.g., X-Rays or CT scans) will face higher costs.

Another clear example of a tax increase on people making less than $250,000 is the limitation on tax-free contributions to a Flexible Spending Arrangement or an FSA. This proposal taxes health benefits a worker receives “for the first time.”

- Under the current tax laws, a worker may contribute to an FSA on a pre-tax basis and use those FSA contributions to pay for co-pays and deductibles tax-free. Currently, there is no limit on these contributions under the tax code. The Reid bill would limit FSA contributions to $2,500 for the first time. This means contributions over $2,500 would be taxed. The average worker that contributes to an FSA earns $55,000 a year. The typical worker that contributes more than $2,500 to their FSA has a serious medical condition. As a result, workers (1) with serious illnesses and (2) earning $55,000 would be paying more in taxes.

Senate floor #008: The bill doesn’t raise taxes?!?

This is a jaw-dropping statement from Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus on the Senate floor yesterday:

I have also heard it argued that health care reform will raise taxes. That, too, is false. In fact, health care reform will provide billions of dollars in tax relief to help American families and small businesses afford quality health insurance tax cuts. The Joint Tax Committee – again bipartisan and which serves both the House and the Senate – tells us, for example, that our bill would provide $40 billion in the tax cuts in the year 2017 alone … $40 billion in tax cuts in the year 2017. The average affected taxpayer will get a tax cut of nearly $450. The average affected taxpayer with an income under $75,000 in 2017 will get a tax cut of more than $1,300.

Let me repeat that. The average affected taxpayer with income under $75,000 in 2017 will get a tax cut of more than $1,300. They will also get a tax cut in earlier years, but it ramps up to that amount in 2017.

The Joint Tax Committee estimate says the Reid amendment would raise taxes by $370 B over ten years. How can it be false to say that this bill raises taxes?

See here for a description of the major tax increases being considered now: Major tax increases in the Reid health care bill

Chairman Baucus appears to be relabeling new entitlement spending as tax cuts. If you look at Table 2 of the CBO letter on the Reid bill, you will see a line for $338 B of “Premium and Cost Sharing Subsidies” under the heading “Changes in Direct Spending (Outlays).” A few lines down, there’s another $118 B of spending for “Reinsurance and Risk Adjustment Payments,” again part of the changes in direct spending. Those are spending increases, not tax cuts.

If someone else can figure out what Chairman Baucus means here, please let me know. As I read the CBO and JCT estimates, the bill raises taxes, and what Chairman Baucus is labeling as tax cuts are in fact spending increases.

Senate floor #007: Not increasing the deficit isn’t good enough

Here is Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus speaking on the Senate floor yesterday:

<

blockquote>Our plan would not increase the government’s commitment to health care. But don’t just take my word for it. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office says:

“

I have also heard it argued that health care reform will increase the budget deficit. That, too, is false, plainly, patently false. The bipartisan Congressional Budget Office says our plan would reduce the Federal deficit by $130 billion within the first 10 years … reduce the deficit in the first 10 years. That trend would continue, the CBO says, over the next decade. During the next decade, CBO says our bill would reduce the deficit roughly $450 billion. That is nearly one-half trillion dollars in deficit reduction, according to the Congressional Budget Office, in the second 10 years.

In both respects, Chairman Baucus is accurately quoting CBO.

Q1: If the federal government’s budgetary commitment to health care is on an unsustainable path, and if this bill “will not increase” that commitment, is that acceptable?

On deficits, here’s what CBO wrote about the Reid amendment’s long-run deficit effect (p. 15):

In the decade after 2019, the gross cost of the coverage expansion would probably exceed 1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), but the added revenues and cost savings would probably be greater. Consequently, CBO expects that the bill, if enacted, would reduce federal budget deficits over the ensuing decade relative to those projected under current law … with a total effect during that decade that is in a broad range around one-quarter percent of GDP. The imprecision of that calculation reflects the even greater degree of uncertainty that attends to it, compared with CBO’s 10-year budget estimates. The expected reduction in deficits would represent a small share of the total deficits that would be likely to arise in that decade under current policies.

Q2: Is that good enough? What happened to “health care reform is entitlement reform” and health care reform as the solution to our long-term deficit problems?

In addition, the Reid amendment excludes all but the first two years’ effects of the so-called “Medicare doc fix,” a multi-hundred billion dollar additional cost, and most analysts think the Congress would be likely to undo some of the Medicare savings proposed in the Reid amendment. The deficit-increasing provisions are certain, while the deficit-reducing provisions are uncertain.

If you’re concerned about long-run budget deficits, you should not make a massive new entitlement spending commitment, exclude a multi-hundred billion spending item that is almost certain to be enacted elsewhere, bet on speculative offsets, all to achieve the unimpressive goal of reducing deficits by “a small share of the total deficits that would be likely to arise in that decade under current policies.”

We need massive future spending reductions to address exploding future deficits, not to redistribute resources to a new entitlement program. This is politically painful but absolutely necessary.