Yesterday’s introductory post to this series gave a broad overview of the fiscal policy debate, listing issues in play at the end of this year, deadlines and timeframes, and three partisan configurations that are worthy of analysis. Today we’ll begin to drill down into the income tax issues.

Income tax rate increases

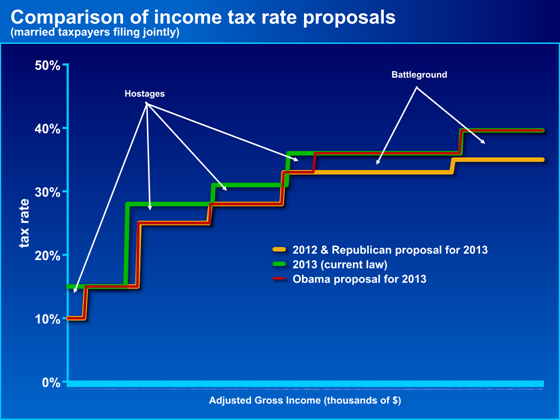

It is easiest to understand the competing proposals with a graph.

If no law is enacted this year, income tax rates will climb from the orange line to the green line. House and Senate Republican leaders propose to keep the current orange rate schedule for one additional year, through 2013. President Obama and Congressional Democratic leaders propose the red line, which matches 2012 current law and the Republican proposal for incomes up to $250K but increases those rates (or “allows them to increase as under current law,” if you prefer) to the green line for incomes above $250K.

I have labeled four regions “hostages.” These are the rate increases that both parties say they prefer not to have take effect, but claim they are wiling to allow rather than sacrifice their position on the top rates (the “battleground”). Whom you label as the hostage-taker probably depends on your preferred policy for incomes above $250K. You can see these hostages go all the way down the income scale. Especially in a weak economic recovery, threatening these hostages is both politically powerful and dangerous – like threatening a busload of nuns and puppies.

Historic recap on tax rate legislation

- The green line was in effect during the Clinton Administration.

- Then-Governor Bush campaigned in 2000 on moving rates down from the green to the orange line. The orange line was enacted in 2001 but the rate cuts were scheduled to be phased in over time. The 2001 law was the result of a bipartisan center-right legislative coalition. Because this coalition fell short of the 60 Senate votes needed to make these rates permanent, they were enacted for 10 years, through 2010.

- In 2003 President Bush proposed, and a Republican Congress enacted, a proposal to accelerate the scheduled rate cuts. This law did not change the ultimate tax rates, it just made them all take effect immediately in 2003. The 2003 law also cut dividend and capital gains tax rates. It was enacted on a nearly straight party-line vote.

- In 2008 then-Senator Obama campaigned on raising tax rates for “the rich.” In 2010 President Obama did the same. Shortly after the 2010 election President Obama flipped, seeking and enacting a deal with Congressional Republicans that extended the orange rate line for two more years in exchange for extending several policies from the 2009 stimulus law. The deals in the 2010 law expire at the end of this year.

- President Obama is once again campaigning aggressively to raise the top income tax rates, and Governor Romney is campaigning to extend (or cut) them. President Obama’s staff have threatened that the President will veto a bill that does not raise the top rates.

- In recent days and weeks, House and Senate Republicans and Senate Democrats have shortened the duration of their proposals to one-year policy changes.

Recent political history on income tax rates

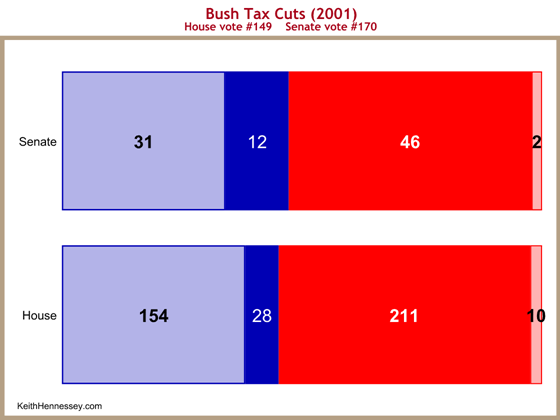

The 2001 tax law, enacted under a Republican president, Republican House, and Republican Senate, included support from a significant block of Democrats. On these graphs, Republicans are in red and Democrats in blue. Heavily shaded areas are aye votes, lightly shaded areas are no votes. Thus in the Senate, 46 Republicans and 12 Democrats voted aye on final passage, while two Republicans and 31 Democrats voted no, thus passing the bill 58-33.

This picture shows a classic center-right legislative alliance. Democratic Senators John Breaux (LA) and now-Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (MT) were the key Democrats in this effort.

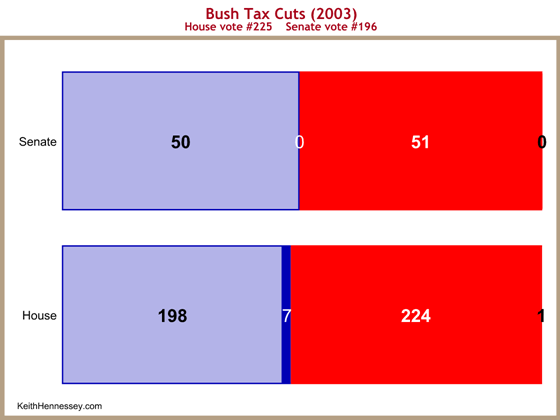

The 2003 law, in contrast, was enacted along nearly party line votes. Vice President Cheney broke the tie in a Senate split 50-50 to cast the deciding vote.

These partisan 2003 votes don’t tell the whole story. In 2003 President Bush first made the argument that the top income tax rates are the rates that apply to successful small business owners. This argument, combined with lingering support from those Democrats who had supported the 2001 law, meant that in early 2003 there was a consensus to accelerate all the income tax rate cuts, including the top rates. In 2003 there was still a bipartisan center-right coalition to keep all income tax rates low.

There was not, however, Democratic support for the other component of President Bush’s proposal, the elimination of the double taxation of dividend income. The 2003 legislative effort became a partisan fight over capital taxation, resulting in the above-displayed partisan final vote as well as today’s 15% rate for capital gains and dividend income.

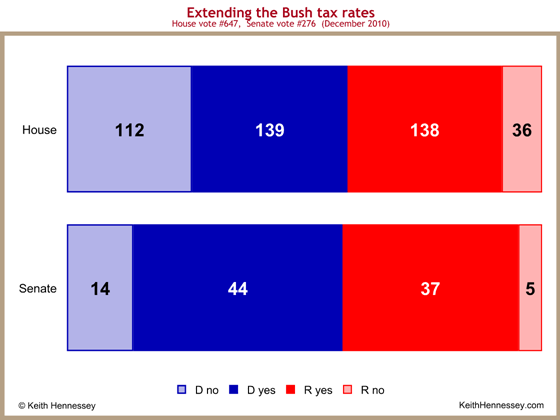

The 2010 tax rate extension law was a deal between President Obama and Republican Congressional leaders. Its vote pattern looks different from the prior two, reflecting a different balance of political forces and policy viewpoints.

This is a centrist legislative coalition. Most Republicans who voted no did so because they opposed several other things in the bill unrelated to the income tax rate extensions. Most Democrats who voted no did so because they didn’t want to extend the top income tax rates.

While in modern history Democrats have always been for higher taxes on the rich relative to Republicans, President Obama’s emphasis on raising taxes on the rich is a relatively new phenomenon. The Clinton team placed their income inequality and tax policy emphasis on the bottom of the income spectrum – specifically, welfare reform and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit. Presidents Clinton and Obama both prioritized distributional issues and taxation, but they placed their emphases at opposite ends of the income spectrum. President Clinton spent much of his legislative capital helping the poor, while President Obama is spending his trying to tax the rich.

Intraparty divisions in 2012

Republicans are more unified this year on tax rate questions than Democrats. President Obama continues to argue for rate increases on incomes above $200K (single) and $250K (married). Several Senate Democrats publicly split with the President, defining rich as incomes above $1M or saying we shouldn’t raise taxes on anyone for a year for fear of undermining an already weak economic recovery. The Senate Democrat bill now being debated sticks with the President’s income levels.

A couple of months ago House Democrats, who are usually the most liberal grouping, took a surprising caucus position that proposed tax increases for those with incomes above $1M. This was strange – to see House Democrats take a position right of the President on taxes. I’m guessing House Democratic leaders did this to prevent moderates and nervous in-cycle Democrats from splitting off and voting with Republicans.

If you look at the 2001 and 2010 votes you can see the underlying political challenge facing the President and Leaders Reid and Pelosi. Democrats often split on questions of taxing the rich. The President is siding with the liberal bloc, at least for now. Some moderate Democrats, those from high income states, and those in tough election cycles are being pressured by their party leaders to support tax increases on income thresholds lower than many of them might prefer right now. Some may also fear being portrayed as opponents of successful small businesses. President Obama and his allies in Congress have a fundamentally difficult task – holding their party together, during a tough election cycle, on a topic on which they have a history of splitting.

At the same time there is a segment of elected Republicans who would be willing to agree to some rate increase on high income taxpayers, if the thresholds are high enough (I’d guess at least $1M). But unlike their moderate Democratic counterparts, there is little political risk for these moderate Republicans to stick publicly with the party position of not raising taxes on anyone. I think this fragment of the Republican party is also smaller than its Democratic counterpart. These moderates may be a legislative challenge for party leaders during post-election negotiations, but they don’t appear to pose a major problem during this period of political positioning and campaigning.

The intraparty division among Democrats presents a tactical opportunity for Republicans. If, for instance, Senate Republicans can get a vote on raising the income thresholds in the Reid bill from $200K/$250K to something higher, they will maximize the pressure on these Democrats. If such an amendment were to pass with Democratic support it would likely raise the income floor for future lame duck tax negotiations.

Tomorrow we’ll look at the policy and political consequences of no tax deal in 2012 and at the tax negotiating landscape in a lame duck session and in early 2013. Remember that income taxes are not the whole tax picture, and taxes are only one of several important parts of the end-of-year fiscal conflict.