The G-20 Summit in pictures

The President hosted the Summit on Financial Markets and the World Economy this past Friday and Saturday at the National Building Museum here in Washington, DC.

This is the first of a two-part note. Part one will describe the mechanics of the Summit and show some photos. Part two will describe the substance.

The action began in mid-October after the President met at Camp David with French President Nicolas Sarkozy and Manuel Barrosso, President of the European Commission:

A statement released after that meeting included the following:

[The three leaders] agreed they would reach out to other world leaders next week with the idea of beginning a series of summits on addressing the challenges facing the global economy.World leaders will be consulted about the idea of a first summit of heads of government to be held in the U.S. soon after the U.S. elections, in order to review progress being made to address the current crisis and to seek agreement on principles of reform needed to avoid a repetition and assure global prosperity in the future. Later summits would be designed to implement agreement on specific steps to be taken to meet those principles.

Four days later, we released a Statement by Press Secretary Dana Perino, which included the following:

Today, the President is inviting the leaders of the Group of 20 countries to a summit in the Washington, D.C. area, on November 15 to discuss financial markets and the global economy.

The G-20 members are: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union.

The Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, the President of the World Bank, the United Nations Secretary-General, and the Chairman of the Financial Stability Forum have also been invited to participate.

Normally a summit like this takes at least a year to plan. The work of an incredible team from the Administration built an incredible summit in only 24 days.

As you can see, the G-20 actually includes 19 States, plus the European Union. The meeting also included the heads of the major international financial institutions (IFIs, pronounced “IF-ees”): the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the U.N. Secretary General, and the Financial Stability Forum. In addition, the final summit meeting included the heads of Spain and the Netherlands.

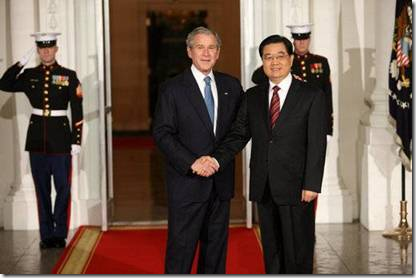

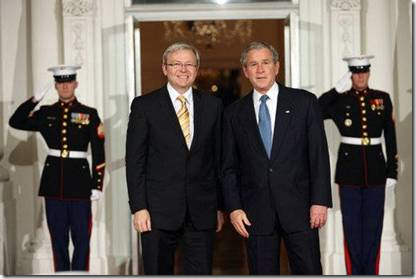

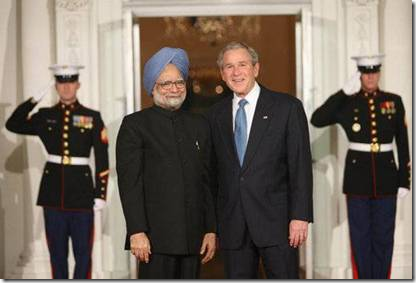

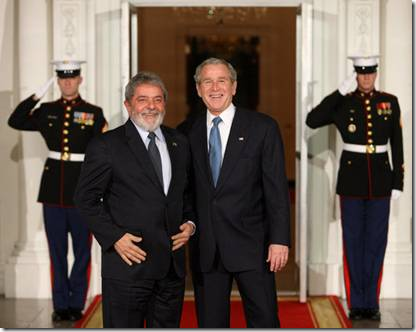

Events began last Friday evening with the President spending almost an hour greeting leaders at the North Portico of the White House.

(Game: Name that Leader. Answers are at the bottom.)

After a reception in the East Room, the President hosted a dinner in the State Dining Room with the leaders. Here he is offering a toast:

We are here because we share a concern about the impact of the global financial crisis on the people of our nations. We share a determination to fix the problems that led to this turmoil. We share a conviction that by working together, we can restore the global economy to the path of long-term prosperity.

Each nation had four representatives in the Saturday summit discussions:

- The leader (for the U.S., President Bush);

- the finance minister (for the U.S., Secretary Paulson);

- the “Sherpa” (for the U.S., Dan Price); and

- the deputy finance minister (for the U.S., Dave McCormick).

The “Sherpa” is an interesting position. It’s derived from the annual G-8 meeting. Each leader appoints a personal representative to carry his or her heavy load in the negotiations leading up to the leaders’ meeting. For the U.S., the Sherpa is always the senior international economic policy advisor in the White House. Dan and Dave led all the negotiations leading up to the G-20 summit (since the U.S. was a host), and they are key players in the success of that summit. In the G-8 context, the Sherpa’s deputy is known as the “sous-sherpa,” and the #3 person is the “yak.”

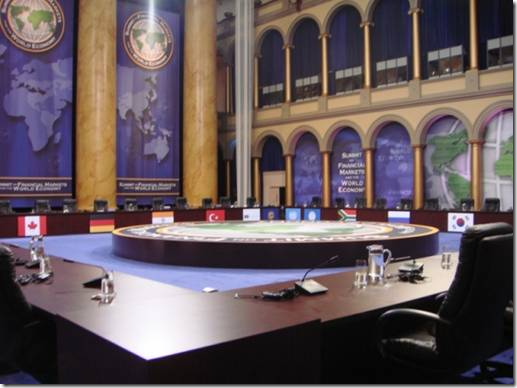

The Saturday summit meeting was held at the beautiful National Building Museum in Washington, DC. Our advance team did all this setup beginning late Thursday night. Some White House staff showed up at 5 AM Saturday to help escort the delegates:

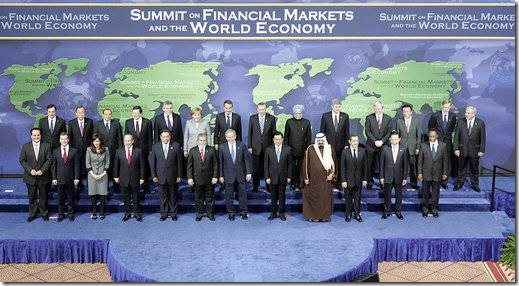

The meeting began with the traditional family photo.”

The leaders then went to the summit session. The inner square is the leaders with their finance ministers. Behind each is a small table with the Sherpa and Finance deputy.

Here’s the President’s view:

Here are two different angles on the room:

And here’s a view from the U.S. Sherpa/finance deputy table:

After the “plenary session,” the Leaders broke for lunch:

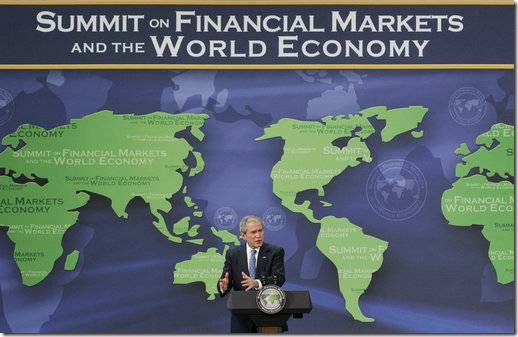

The Leaders left after lunch (one report said there were over 400 vehicles in the motorcades combined), while the President made a statement to the press:

Part two of this note looks at what was actually accomplished at the summit.

Answers to Name that Leader:

- Mexican President Felipe Calderon

- Chinese President Hu Jintao

- Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd

- Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh

- Russian President Dmitryi Medvedev

- Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of Brazil (aka “Lula”)

The President’s speech on financial markets and the world economy

President Bush spoke at the Manhattan Institute today on financial markets and the world economy.

This speech is a prelude to the financial summit the President will host this weekend. I’ll write separately about the Summit, and about the elements of today’s speech that talk about principles for reform.

I want to draw your attention to two parts of the speech.

The first is where the President reprises his explanation for the economic causes of our current situation.

Over the past decade, the world experienced a period of strong economic growth. Nations accumulated huge amounts of savings, and looked for safe places to invest them. Because of our attractive political, legal, and entrepreneurial climates, the United States and other developed nations received a large share of that money.

The massive inflow of foreign capital, combined with low interest rates, produced a period of easy credit. And that easy credit especially affected the housing market. Flush with cash, many lenders issued mortgages and many borrowers could not afford them. Financial institutions then purchased these loans, packaged them together, and converted them into complex securities designed to yield large returns. These securities were then purchased by investors and financial institutions in the United States and Europe and elsewhere — often with little analysis of their true underlying value.

The financial crisis was ignited when booming housing markets began to decline. As home values dropped, many borrowers defaulted on their mortgages, and institutions holding securities backed by those mortgages suffered serious losses. Because of outdated regulatory structures and poor risk management practices, many financial institutions in America and Europe were too highly leveraged. When capital ran short, many faced severe financial jeopardy. This led to high-profile failures of financial institutions in America and Europe, led to contractions and widespread anxiety — all of which contributed to sharp declines in the equity markets.

These developments have placed a heavy burden on hardworking people around the world. Stock market drops have eroded the value of retirement accounts and pension funds. The tightening of credit has made it harder for families to borrow money for cars or home improvements or education of the children. Businesses have found it harder to get loans to expand their operations and create jobs. Many nations have suffered job losses, and have serious concerns about the worsening economy. Developing nations have been hit hard as nervous investors have withdrawn their capital.

The second is the last two pages of the speech. I tried to summarize and excerpt from this, and instead have concluded that the best thing I can do is allow the President’s words to speak for themselves.

All this leads to the most important principle that should guide our work: While reforms in the financial sector are essential, the long-term solution to today’s problems is sustained economic growth. And the surest path to that growth is free markets and free people. (Applause.)

This is a decisive moment for the global economy. In the wake of the financial crisis, voices from the left and right are equating the free enterprise system with greed and exploitation and failure. It’s true this crisis included failures — by lenders and borrowers and by financial firms and by governments and independent regulators. But the crisis was not a failure of the free market system. And the answer is not to try to reinvent that system. It is to fix the problems we face, make the reforms we need, and move forward with the free market principles that have delivered prosperity and hope to people all across the globe.

Like any other system designed by man, capitalism is not perfect. It can be subject to excesses and abuse. But it is by far the most efficient and just way of structuring an economy. At its most basic level, capitalism offers people the freedom to choose where they work and what they do, the opportunity to buy or sell products they want, and the dignity that comes with profiting from their talent and hard work. The free market system provides the incentives that lead to prosperity — the incentive to work, to innovate, to save, to invest wisely, and to create jobs for others. And as millions of people pursue these incentives together, whole societies benefit.

Free market capitalism is far more than economic theory. It is the engine of social mobility — the highway to the American Dream. It’s what makes it possible for a husband and wife to start their own business, or a new immigrant to open a restaurant, or a single mom to go back to college and to build a better career. It is what allowed entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley to change the way the world sells products and searches for information. It’s what transformed America from a rugged frontier to the greatest economic power in history — a nation that gave the world the steamboat and the airplane, the computer and the CAT scan, the Internet and the iPod.

Ultimately, the best evidence for free market capitalism is its performance compared to other economic systems. Free markets allowed Japan, an island with few natural resources, to recover from war and grow into the world’s second-largest economy. Free markets allowed South Korea to make itself into one of the most technologically advanced societies in the world. Free markets turned small areas like Singapore and Hong Kong and Taiwan into global economic players. Today, the success of the world’s largest economies comes from their embrace of free markets.

Meanwhile, nations that have pursued other models have experienced devastating results. Soviet communism starved millions, bankrupted an empire, and collapsed as decisively as the Berlin Wall. Cuba, once known for its vast fields of cane, is now forced to ration sugar. And while Iran sits atop giant oil reserves, its people cannot put enough gasoline in its — in their cars.

The record is unmistakable: If you seek economic growth, if you seek opportunity, if you seek social justice and human dignity, the free market system is the way to go. (Applause.) And it would be a terrible mistake to allow a few months of crisis to undermine 60 years of success.

Just as important as maintaining free markets within countries is maintaining the free movement of goods and services between countries. When nations open their markets to trade and investment, their businesses and farmers and workers find new buyers for their products. Consumers benefit from more choices and better prices. Entrepreneurs can get their ideas off the ground with funding from anywhere in the world. Thanks in large part to open markets, the volume of global trade today is nearly 30 times greater than it was six decades ago — and some of the most dramatic gains have come in the developing world.

As President, I have seen the transformative power of trade up close. I’ve been to a Caterpillar factory in East Peoria, Illinois, where thousands of good-paying American jobs are supported by exports. I’ve walked the grounds of a trade fair in Ghana, where I met women who support their families by exporting handmade dresses and jewelry. I’ve spoken with a farmer in Guatemala who decided to grow high-value crops he could sell overseas — and helped create more than 1,000 jobs.

Stories like these show why it is so important to keep markets open to trade and investment. This openness is especially urgent during times of economic strain. Shortly after the stock market crash in 1929, Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley tariff — a protectionist measure designed to wall off America’s economy from global competition. The result was not economic security. It was economic ruin. And leaders around the world must keep this example in mind, and reject the temptation of protectionism. (Applause.)

There are clear-cut ways for nations to demonstrate the commitment to open markets. The United States Congress has an immediate opportunity by approving free trade agreements with Colombia, Peru*, and South Korea. America and other wealthy nations must also ensure this crisis does not become an excuse to reverse our engagement with the developing world. And developing nations should continue policies that foster enterprise and investment. As well, all nations should pledge to conclude a framework this year that leads to a successful Doha agreement.

We’re facing this challenge together and we’re going to get through it together. The United States is determined to show the way back to economic growth and prosperity. I know some may question whether America’s leadership in the global economy will continue. The world can be confident that it will, because our markets are flexible and we can rebound from setbacks. We saw that resilience in the 1940s, when America pulled itself out of Depression, marshaled a powerful army, and helped save the world from tyranny. We saw that resilience in the 1980s, when Americans overcame gas lines, turned stagflation into strong economic growth, and won the Cold War. We saw that resilience after September the 11th, 2001, when our nation recovered from a brutal attack, revitalized our shaken economy, and rallied the forces of freedom in the great ideological struggle of the 21st century.

The world will see the resilience of America once again. We will work with our partners to correct the problems in the global financial system. We will rebuild our economic strength. And we will continue to lead the world toward prosperity and peace.

Are banks hoarding taxpayer investments?

We’re getting questions about whether banks that receive taxpayer funds from the Treasury are “hoarding” that cash, rather than using it to support lending.

We know that banks aren’t hoarding yet, since at most they’ve had cash for two days.

Remember that there is a two-fold purpose to this program: (1) strengthen the banking system (prevent a collapse), and (2) increase lending.

We think that profit-maximizing banks have an incentive to lend.

In some cases, when a bank does not use new capital to support additional lending, they are still accomplishing our policy goal of a strengthened financial system.

So while we can’t tell you that the anecdotal reports of other plans for the cash are provably wrong, we think these reports are largely distractions from what banks will actually do with your tax dollars.

And we believe the “solutions” that are being suggested to “ensure” that every taxpayer dollar goes directly to support more lending would be counterproductive. We want banks to use the taxpayer investments both to strengthen the banking system and to increase lending. Since this is a voluntary program for banks, we cannot mandate the specific use of each taxpayer dollar, and if we try, banks won’t participate.

Banks are undercapitalized. They need more capital so that:

- they can increase their capital cushion, and thereby lower their probability of being insolvent;

- other banks and other financial institutions have the confidence needed to loan them short-term funds; and

- they can support more lending.

There are three goals here, not one. If a bank takes an equity investment and if that investment helps with any of the above goals, that’s a good thing. The most effective way to increase lending is to move toward a banking system that has more capital, more liquidity, fewer projected failures, and is more efficient than today’s system.

If, for instance, a bank has a capital hole because it lost a lot of money on bad investments in mortgage-backed securities, and if it’s at risk of being insolvent, then more capital will reduce that risk and make it more likely that that bank will continue operating and (eventually) lend more. Even if that bank doesn’t use this specific investment from Treasury to support more lending, but instead to strengthen its own capital cushion, if that taxpayer investment keeps that bank from going out of business, that’s a good thing, and lending will increase over time.

Similarly, if a bank takes an equity investment from Treasury, and uses some of that investment to buy another bank, there’s a good chance that the bank being purchased is in weak financial shape and at risk of going bankrupt. The taxpayer investment is therefore going to keep that lending capacity in the system, and to provide a strong capital cushion for the new combined bank. Again, while there’s no new immediate lending in this specific case, the outcome accomplishes one of our goals – lowering the probability of a bank going bankrupt.

Now suppose a bank takes some of the Treasury investment and keeps it as cash in their vault. Is that a bad thing? Not necessarily. In a highly volatile financial environment, it may make sense for an individual, business, or bank to keep more cash on hand, just in case they need it. In this case, some of that equity investment may strengthen a bank’s liquidity as it adapts to an environment with skittish depositors, borrowers, and lenders. That’s not directly supporting new lending, but increased liquidity is still a good thing that makes the banking system work better.

Banks make money by lending. And these taxpayer investments are not free to the bank – the bank must make dividend payments to the Treasury for that investment. The terms of the agreement are that each bank must pay a fixed 5 percent dividend for the first five years, and then a fixed 9 percent dividend after that. So unless a bank wants to lose money (and we can safely assume they don’t), they will need to get a return of better than 5 percent to make the investment worthwhile. Simply put, we expect that banks will work to maximize their profit, and that most will do that by lending to businesses and consumers, and that they will take some of the returns from that lending to pay back the Treasury/taxpayer.

If a bank uses more capital to do something unproductive (like pay their employees bigger bonuses), rather than to strengthen their capital cushion (good), buy another failing bank (also good), or support more lending (even better), then we think that bank could be losing money on their new investment, since they still have to pay Treasury a 5 percent dividend. And the law requires that banks that take an investment limit the compensation of their highest-paid executives.

Finally, it’s impossible for more than two days of hoarding to have occurred so far. It took some time for all the lawyers to work out all the details, and the cash is just now beginning to flow. The first cash left the Treasury Department on Tuesday. So the press reports you may have seen are entirely speculative reports of what some claim they may do with their new capital.

What about the NY Times’ proposal?

If Treasury won’t impose conditions, Congress must, including a requirement that banks accepting bailout money increase their loans to creditworthy borrowers and limit their acquisitions to failing banks, such as those listed as troubled by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

This is a stunning suggestion. Part of the reason we’re in this financial mess is that the government pushed lenders to make loans that didn’t make financial sense.

There is a philosophical difference here. Our approach is to create incentives for banks to strengthen themselves and the economy by relying on a profit motive. The NY Times’ approach is to try to have government mandate certain outcomes by force, and tell banks, “If you take this investment, you must do X, Y, and Z with the money, and you must not do A, B, or C.” The law already requires:

- limits on incentive compensation for senior executives;

- clawback of compensation for senior executives if financial statements are later proven to be materially inaccurate;

- prohibition of “golden parachutes”;

- a new limit on tax deductibility of executive compensation; and

- for those firms that take an equity investment, restrictions on dividends and share repurchases.

The Times forgets that this program is voluntary. If the government tries to mandate a use for the funds that a bank would not otherwise choose to do, that bank just won’t take the funds. Make the requirements and restrictions onerous enough, and you’ll end up right where we started – with a dangerously undercapitalized banking system.

What caused this financial mess?

President Bush spoke today about the financial crisis to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

I’m going to use the President’s speech as an opportunity to explain to a non-financial audience what the Federal government did this week and why. I will oversimplify in many cases, and will gloss over many details. I don’t claim that the description below is comprehensive. But it is, we think, a good starting point for discussion.

This is a story that evolves over time as we learn more, and will be debated by economists and historians long after we’re gone.

- We begin with a global credit boom. A dramatic increase in worldwide saving outside the United States, and especially in Asia and the Middle East, meant there was a lot of money to lend. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke referred to this as a “global savings glut.” The U.S. has a productive economy and a strong legal framework that protects investors, so a lot of this capital was attracted to the U.S. This lowered interest rates here, creating abundant and inexpensive credit. This was particularly true for riskier borrowers – as the supply of loanable funds increased, the interest rates charged to these borrowers came down a lot, making it easier for them to get loans. In many cases this was a good thing – many low-income people who had previously been unable to buy a home were able to do so. At the same time, an economist would say that “credit spreads narrowed dramatically,” and many would say this led to an underpricing of risk. Lots of lenders seeking higher yields made increasingly risky investments.While most of the focus has been on housing, and I’ll use housing to explain the rest of the story, the underpricing of risk existed in other markets as well (e.g., commercial real estate). Also note that the credit boom was not confined to the U.S. – Australia, the U.K., France, and Spain also experienced housing or credit booms.

- We then look at a domestic housing boom. Cheap credit and low interest rates contributed to a building boom, soaring housing prices, and ultimately an excess supply of housing. Normally you’d expect about 1.6 million homes to be built each year. At the peak of this boom, about 2 1/2 million houses were being built each year. At a normal time, there’s about a 5 1/2 month supply of unsold inventory of homes; now there’s about a 10 month supply. When there’s excess supply, prices drop and construction of new homes plummets. This last factor meant that the “residential construction” component of GDP was shrinking, and caused an overall drag to economic growth beginning in early 2006.

- Risky mortgages proliferated. Low interest rates combined with relaxed lending standards, a new model of mortgage origination, and innovations in mortgage products to dramatically expand the number of Americans who could get mortgages and buy homes. At the same time, these factors also expanded the universe of people who purchased mortgages and homes they could not afford.In an imperfect lending system, you’re always trading off between helping too few deserving people, and too many really bad risks who will never be able to pay off their loans. The expansion of credit and innovation in mortgage markets moved the pendulum toward a lot more people being able to borrow and buy homes than had previously occurred. Many of these people who previously would not have been offered credit are now living in their homes, paying their mortgage every month. This is a good thing. At the same time, these changes allowed others to purchase mortgages and homes that they could not afford.

- You can try to minimize this tradeoff by doing things like fixing the lending disclosure rules, and changing requirements on lenders to make sure that a borrower will be able to afford the highest interest rate of the mortgage, and not just the teaser rate. But even after you’ve made these kinds of fixes (which the Fed did late in 2007), there will still always be a tradeoff and a value choice to make: do you want to help more higher-risk low income people own homes, at the cost of having more defaults and more bad lenders and borrowers abusing the system? Or do you want fewer abuses of the system, at the cost of fewer responsible low-income and high-risk people owning homes?

- We then move to the secondary market for mortgages. Mortgages were bundled, guaranteed, securitized, and sold to financial institutions (especially banks). DETOUR: What is a mortgage-backed security?You get a mortgage from Bob’s Bank. You will make monthly mortgage payments to Bob’s Bank for the next 30 years. 99 of your neighbors get similar mortgages from Bob. Bob then sells the 100 mortgages to the company Fannie Mae (or Freddie Mac, or a fully private securitization firm). Fannie collects a fee from Bob and slaps a guarantee onto each mortgage – if you default, Fannie will pay the rest of the mortgage due to Bob’s Bank, or whoever owns it.Now imagine that each of your monthly mortgage payments is a pancake, and so your mortgage is a big vertical stack of 360 payments/pancakes (30 year mortgage X 12 monthly payments per year). Fannie Mae lines up the 100 stacks of pancakes/payments side-by-side, and then takes a slice of the pancake/payments stacks (e.g., the bottom pancake/payment from each stack, or in the usual case with Fannie Mae, a vertical slice of each stack). That slice is a mortgage-backed security (MBS) that consists of a portion of the payments from all 100 mortgages. Fannie Mae then sells the MBS slices back to Bob, after charging him a fee for the service. Bob then sells those mortgage-backed securities to investors for cash, which he can turn around and use to offer new mortgages to other homebuyers.Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac did the bulk of this guarantee and securitization business, while other firms securitized lower quality subprime and Alt-A loans. A deeper analysis could explain how this securitization contributed to problems in these secondary markets. Creative financial engineers further sliced and diced these mortgage-backed securities, breaking risk apart into little pieces and combining them in interesting, creative, and almost completely incomprehensible ways. (Imagine flipping and swapping some pancakes around before slicing them and you’ll have a feel for it).

- Many banks and other large financial institutions, including some insurance companies, and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac themselves, bought and held these mortgage-backed and other complex securities. These investors all made the same incorrect assumption: they assumed that anything mortgage-related would be safe and yield a good return. While most mortgages are safe investments, investors did not correctly understand that some of these assets were quite risky. They didn’t really know what they were buying for two reasons: (1) the underlying information about some of the mortgages was bad, because some of the loans were based on poor information (e.g. “no documentation loans”) or were made to people who were higher credit risks; and (2) many buyers of complex securities did not understand how the sophisticated financial engineering affected the risks built into these securities. In some cases, investors relied on the Fannie/Freddie brand name and didn’t do their own homework. Others relied solely on credit rating agencies that later turned out to be wrong in their risk assessments.

- Banks and other financial institutions that bought mortgage-backed securities (and other mortgage-related investments) lost a lot of money when these securities later declined in value. Because many of these institutions (especially large investment banks) were highly leveraged, they faced a greater risk of failure from a bad bet, and the consequences of that failure were much greater. Many of those banks that did not fail still lost a lot of their capital. Some of these large financial institutions were so big and so interconnected with other institutions, that their failure would create a domino effect. This is what we call “too big to fail,” which should more precisely be called “too big and interconnected to fail suddenly.”

Example of low leverage

If an investment bank has $10 of capital and makes $50 of loans, it is leveraged 5 to 1. (The other $40 to lend comes from deposits or borrowing.) If that $50 of loans loses 10% of its value and pays back only $45, then the bank has lost $5, which is half of its $10 of capital.

Example of high leverage

The same bank with $10 of capital makes $200 of loans, and is leveraged 20 to 1. If that $200 of loans loses 10% of its value and pays only $180, then the bank has lost $20. All of its capital is gone (the bank is bankrupt), and the bank is $10 in the hole. Because this bank was highly leveraged, it took on greater risk of failure.

The major investment banks were levered 25 to 1. That’s like buying a house with only 4% down – if your home price declines by 5%, you’re “underwater.” And since many of these large financial firms relied on short-term financing to run their operations, when lenders started to get nervous and pull back from their short-term loans to these large firms, things rapidly spiraled downward.

That story gets us up to the point of a large bank (we’ll call it Big Bank) ending up in a bad position in two ways:

- Big Bank lost a lot of capital because the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) it bought have declined tremendously in value.

- Big Bank is still holding the MBS on their balance sheet. Nobody wants to buy these MBS. And if housing prices or market conditions get even worse than expected, those MBS will decline in value even more. So Big Bank has a security that is illiquid and contains the downside risk of further losses.

Big Bank’s problems show up in any combination of three different ways:

- Capital – Because Big Bank has too little capital, they can’t lend as much. This hurts everyone in the economy who needs to borrow – students who want student loans, drivers who want car loans, small business owners who need credit to operate and to expand, farmers who borrow for seed and fertilizer, and others.

- Liquidity – Banks normally loan money to each other for short periods of time. But now Large Bank doesn’t want to lend to Big Bank, because Large Bank fears Big Bank might be insolvent and not be around to pay them back. So Large Bank charges Big Bank more (a higher interest rate) for this short-term borrowing. We have seen this in dramatic fashion as the interest rate that banks charge either, called the London Interbank Offerer Rate (LIBOR) has spiked up. Large Bank may shorten the term of their lending – being willing to loan to Big Bank overnight, but not for 30 days. In an extreme case, Large Bank may not lend at all to Big Bank. To oversimplify, banks don’t trust each other enough to lend. This breakdown in trust/confidence among large financial institutions is a core problem in our financial system.

- Solvency – At the extreme, a bank could lose so much capital that it is clearly insolvent. In less severe cases, either depositors or lenders to that bank might lose confidence that the bank was viable. Depositors might withdraw their funds from the bank, or lenders to that bank might stop lending. Either one of these could cause a “run on the bank” that could ultimately force the bank to shut down.

Conclusion

Many banks and other financial institutions, and especially big ones, lost a lot of money on bad mortgage-related investments. This caused them to lose a lot of their capital, and in many cases some of their assets are illiquid and pose additional downside risk to their balance sheets. This hurts those banks’ ability to lend, it hurts their ability to remain liquid and borrow short-term cash from other banks, and in extreme cases it can lead to a run on the bank (of depositors, lenders, or both) and insolvency.

I am indebted to Eddie Lazear and Donald Marron of our Council of Economic Advisers for their help with this note. All mistakes are my own.

President’s Working Group on Financial Markets documents

The President’s Working Group on Financial Markets met at 8:30 AM today to announce the specifics of the new policy actions described by the President in the Rose Garden earlier this morning.

This note is just a collection of primary source documents from today’s announcement. Generalists will likely be interested in the first six documents, as well as #10. The other documents will be of interest primarily to financial experts.

Here you will find:

- The President’s remarks in the Rose Garden this morning

- A joint statement by Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, and FDIC Chairman Sheila Bair

- A summary document that describes the package as a whole

- Statement by Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson

- Statement by Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke

- Statement by FDIC Chairman Sheila Bair

Treasury documents

- Capital Purchase program description

- Capital Purchase program term sheet

- Executive Compensation rules

- Speech by Interim Assistant Secretary for Financial Stability Neel Kashkari on Implementation of the Economic Stabilization Act (delivered Monday 13 October)

FDIC documents

Fed documents

Rose Garden Statement by President Bush on financial markets

President Bush spoke at 8:02 AM this morning in the Rose Garden.

Good morning. I just completed a meeting with my working group on financial markets. We discussed the unprecedented and aggressive steps the federal government is taking to address the financial crisis. Over the past few weeks, my administration has worked with both parties in Congress to pass a financial rescue plan. Federal agencies have moved decisively to shore up struggling institutions and stabilize our markets. And the United States has worked with partners around the world to coordinate our actions to get our economies back on track.

This weekend, I met with finance ministers from the G7 and the G20 — organizations representing some of the world’s largest and fastest-growing economies. We agreed on a coordinated plan for action to provide new liquidity, strengthen financial institutions, protect our citizens’ savings, and ensure fairness and integrity in the markets. Yesterday, leaders in Europe moved forward with this plan. They announced significant steps to inject capital into their financial systems by purchasing equity in major banks. And they announced a new effort to jumpstart lending by providing temporary government guarantees for bank loans. These are wise and timely actions, and they have the full support of the United States.

Today, I am announcing new measures America is taking to implement the G7 action plan and strengthen banks across our country.

First, the federal government will use a portion of the $700 billion financial rescue plan to inject capital into banks by purchasing equity shares. This new capital will help healthy banks continue making loans to businesses and consumers. And this new capital will help struggling banks fill the hole created by losses during the financial crisis, so they can resume lending and help spur job creation and economic growth. This is an essential short-term measure to ensure the viability of America’s banking system. And the program is carefully designed to encourage banks to buy these shares back from the government when the markets stabilize and they can raise capital from private investors.

Second, and effective immediately, the FDIC will temporarily guarantee most new debt issued by insured banks. This will address one of the central problems plaguing our financial system — banks have been unable to borrow money, and that has restricted their ability to lend to consumers and businesses. When money flows more freely between banks, it will make it easier for Americans to borrow for cars, and homes, and for small businesses to expand.

Third, the FDIC will immediately and temporarily expand government insurance to cover all non-interest bearing transaction accounts. These accounts are used primarily by small businesses to cover day-to-day operations. By insuring every dollar in these accounts, we will give small business owners peace of mind and bring stability to the — and bring greater stability to the banking system.

Fourth, the Federal Reserve will soon finalize work on a new program to serve as a buyer of last resort for commercial paper. This is a key source of short-term financing for American businesses and financial institutions. And by unfreezing the market for commercial paper, the Federal Reserve will help American businesses meet payroll, and purchase inventory, and invest to create jobs.

In a few moments, Secretary Paulson and other members of my Working Group on Financial Markets will explain these steps in greater detail. They will make clear that each of these new programs contains safeguards to protect the taxpayers. They will make clear that the government’s role will be limited and temporary. And they will make clear that these measures are not intended to take over the free market, but to preserve it.

The measures I have announced today are the latest steps in this systematic approach to address the crisis. I know Americans are deeply concerned about the stress in our financial markets, and the impact it is having on their retirement accounts, and 401(k)s, and college savings, and other investments. I recognize that the action leaders are taking here in Washington and in European capitals can seem distant from those concerns. But these efforts are designed to directly benefit the American people by stabilizing our overall financial system and helping our economy recover.

It will take time for our efforts to have their full impact, but the American people can have confidence about our long-term economic future. We have a strategy that is broad, that is flexible, and that is aimed at the root cause of our problem. Nations around the world are working together to overcome this challenge. And with confidence and determination, we will return our economies to the path of growth and prosperity.

Thank you.

Address by President Bush on financial markets

President Bush gave a major policy address on the State Floor of the White House this evening.

THE WHITE HOUSE

State Floor

9:01 P.M. EDT

THE PRESIDENT: Good evening. This is an extraordinary period for America’s economy. Over the past few weeks, many Americans have felt anxiety about their finances and their future. I understand their worry and their frustration. We’ve seen triple-digit swings in the stock market. Major financial institutions have teetered on the edge of collapse, and some have failed. As uncertainty has grown, many banks have restricted lending. Credit markets have frozen. And families and businesses have found it harder to borrow money.

We’re in the midst of a serious financial crisis, and the federal government is responding with decisive action. We’ve boosted confidence in money market mutual funds, and acted to prevent major investors from intentionally driving down stocks for their own personal gain.

Most importantly, my administration is working with Congress to address the root cause behind much of the instability in our markets. Financial assets related to home mortgages have lost value during the housing decline. And the banks holding these assets have restricted credit. As a result, our entire economy is in danger. So I’ve proposed that the federal government reduce the risk posed by these troubled assets, and supply urgently-needed money so banks and other financial institutions can avoid collapse and resume lending.

This rescue effort is not aimed at preserving any individual company or industry — it is aimed at preserving America’s overall economy. It will help American consumers and businesses get credit to meet their daily needs and create jobs. And it will help send a signal to markets around the world that America’s financial system is back on track.

I know many Americans have questions tonight: How did we reach this point in our economy? How will the solution I’ve proposed work? And what does this mean for your financial future? These are good questions, and they deserve clear answers.

First, how did our economy reach this point?

Well, most economists agree that the problems we are witnessing today developed over a long period of time. For more than a decade, a massive amount of money flowed into the United States from investors abroad, because our country is an attractive and secure place to do business. This large influx of money to U.S. banks and financial institutions — along with low interest rates — made it easier for Americans to get credit. These developments allowed more families to borrow money for cars and homes and college tuition — some for the first time. They allowed more entrepreneurs to get loans to start new businesses and create jobs.

Unfortunately, there were also some serious negative consequences, particularly in the housing market. Easy credit — combined with the faulty assumption that home values would continue to rise — led to excesses and bad decisions. Many mortgage lenders approved loans for borrowers without carefully examining their ability to pay. Many borrowers took out loans larger than they could afford, assuming that they could sell or refinance their homes at a higher price later on.

Optimism about housing values also led to a boom in home construction. Eventually the number of new houses exceeded the number of people willing to buy them. And with supply exceeding demand, housing prices fell. And this created a problem: Borrowers with adjustable rate mortgages who had been planning to sell or refinance their homes at a higher price were stuck with homes worth less than expected — along with mortgage payments they could not afford. As a result, many mortgage holders began to default.

These widespread defaults had effects far beyond the housing market. See, in today’s mortgage industry, home loans are often packaged together, and converted into financial products called “mortgage-backed securities.” These securities were sold to investors around the world. Many investors assumed these securities were trustworthy, and asked few questions about their actual value. Two of the leading purchasers of mortgage-backed securities were Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Because these companies were chartered by Congress, many believed they were guaranteed by the federal government. This allowed them to borrow enormous sums of money, fuel the market for questionable investments, and put our financial system at risk.

The decline in the housing market set off a domino effect across our economy. When home values declined, borrowers defaulted on their mortgages, and investors holding mortgage-backed securities began to incur serious losses. Before long, these securities became so unreliable that they were not being bought or sold. Investment banks such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers found themselves saddled with large amounts of assets they could not sell. They ran out of the money needed to meet their immediate obligations. And they faced imminent collapse. Other banks found themselves in severe financial trouble. These banks began holding on to their money, and lending dried up, and the gears of the American financial system began grinding to a halt.

With the situation becoming more precarious by the day, I faced a choice: To step in with dramatic government action, or to stand back and allow the irresponsible actions of some to undermine the financial security of all.

I’m a strong believer in free enterprise. So my natural instinct is to oppose government intervention. I believe companies that make bad decisions should be allowed to go out of business. Under normal circumstances, I would have followed this course. But these are not normal circumstances. The market is not functioning properly. There’s been a widespread loss of confidence. And major sectors of America’s financial system are at risk of shutting down.

The government’s top economic experts warn that without immediate action by Congress, America could slip into a financial panic, and a distressing scenario would unfold:

More banks could fail, including some in your community. The stock market would drop even more, which would reduce the value of your retirement account. The value of your home could plummet. Foreclosures would rise dramatically. And if you own a business or a farm, you would find it harder and more expensive to get credit. More businesses would close their doors, and millions of Americans could lose their jobs. Even if you have good credit history, it would be more difficult for you to get the loans you need to buy a car or send your children to college. And ultimately, our country could experience a long and painful recession.

Fellow citizens: We must not let this happen. I appreciate the work of leaders from both parties in both houses of Congress to address this problem — and to make improvements to the proposal my administration sent to them. There is a spirit of cooperation between Democrats and Republicans, and between Congress and this administration. In that spirit, I’ve invited Senators McCain and Obama to join congressional leaders of both parties at the White House tomorrow to help speed our discussions toward a bipartisan bill.

I know that an economic rescue package will present a tough vote for many members of Congress. It is difficult to pass a bill that commits so much of the taxpayers’ hard-earned money. I also understand the frustration of responsible Americans who pay their mortgages on time, file their tax returns every April 15th, and are reluctant to pay the cost of excesses on Wall Street. But given the situation we are facing, not passing a bill now would cost these Americans much more later.

Many Americans are asking: How would a rescue plan work?

After much discussion, there is now widespread agreement on the principles such a plan would include. It would remove the risk posed by the troubled assets — including mortgage-backed securities — now clogging the financial system. This would free banks to resume the flow of credit to American families and businesses. Any rescue plan should also be designed to ensure that taxpayers are protected. It should welcome the participation of financial institutions large and small. It should make certain that failed executives do not receive a windfall from your tax dollars. It should establish a bipartisan board to oversee the plan’s implementation. And it should be enacted as soon as possible.

In close consultation with Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, and SEC Chairman Chris Cox, I announced a plan on Friday. First, the plan is big enough to solve a serious problem. Under our proposal, the federal government would put up to $700 billion taxpayer dollars on the line to purchase troubled assets that are clogging the financial system. In the short term, this will free up banks to resume the flow of credit to American families and businesses. And this will help our economy grow.

Second, as markets have lost confidence in mortgage-backed securities, their prices have dropped sharply. Yet the value of many of these assets will likely be higher than their current price, because the vast majority of Americans will ultimately pay off their mortgages. The government is the one institution with the patience and resources to buy these assets at their current low prices and hold them until markets return to normal. And when that happens, money will flow back to the Treasury as these assets are sold. And we expect that much, if not all, of the tax dollars we invest will be paid back.

A final question is: What does this mean for your economic future?

The primary steps — purpose of the steps I have outlined tonight is to safeguard the financial security of American workers and families and small businesses. The federal government also continues to enforce laws and regulations protecting your money. The Treasury Department recently offered government insurance for money market mutual funds. And through the FDIC, every savings account, checking account, and certificate of deposit is insured by the federal government for up to $100,000. The FDIC has been in existence for 75 years, and no one has ever lost a penny on an insured deposit — and this will not change.

Once this crisis is resolved, there will be time to update our financial regulatory structures. Our 21st century global economy remains regulated largely by outdated 20th century laws. Recently, we’ve seen how one company can grow so large that its failure jeopardizes the entire financial system.

Earlier this year, Secretary Paulson proposed a blueprint that would modernize our financial regulations. For example, the Federal Reserve would be authorized to take a closer look at the operations of companies across the financial spectrum and ensure that their practices do not threaten overall financial stability. There are other good ideas, and members of Congress should consider them. As they do, they must ensure that efforts to regulate Wall Street do not end up hampering our economy’s ability to grow.

In the long run, Americans have good reason to be confident in our economic strength. Despite corrections in the marketplace and instances of abuse, democratic capitalism is the best system ever devised. It has unleashed the talents and the productivity, and entrepreneurial spirit of our citizens. It has made this country the best place in the world to invest and do business. And it gives our economy the flexibility and resilience to absorb shocks, adjust, and bounce back.

Our economy is facing a moment of great challenge. But we’ve overcome tough challenges before — and we will overcome this one. I know that Americans sometimes get discouraged by the tone in Washington, and the seemingly endless partisan struggles. Yet history has shown that in times of real trial, elected officials rise to the occasion. And together, we will show the world once again what kind of country America is — a nation that tackles problems head on, where leaders come together to meet great tests, and where people of every background can work hard, develop their talents, and realize their dreams.

Thank you for listening. May God bless you.

Rose Garden Statement by President Bush on the Economy

Here’s what President Bush said at 10:45 AM today in the Rose Garden.

This is really important.

Good morning. I thank Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, and SEC Chairman Chris Cox for joining me today.

This is a pivotal moment for America’s economy. Problems that originated in the credit markets — and first showed up in the area of subprime mortgages — have spread throughout our financial system. This has led to an erosion of confidence that has frozen many financial transactions, including loans to consumers and to businesses seeking to expand and create jobs. As a result, we must act now to protect our nation’s economic health from serious risk.

There will be ample opportunity to debate the origins of this problem. Now is the time to solve it. In our nation’s history, there have been moments that require us to come together across party lines to address major challenges. This is such a moment. Last night, Secretary Paulson and Chairman Bernanke and Chairman Cox met with congressional leaders of both parties — and they had a very good meeting. I appreciate the willingness of congressional leaders to confront this situation head on.

Our system of free enterprise rests on the conviction that the federal government should interfere in the marketplace only when necessary. Given the precarious state of today’s financial markets — and their vital importance to the daily lives of the American people — government intervention is not only warranted, it is essential.

In recent weeks, the federal government has taken a series of measures to help promote stability in the overall economy. To avoid severe disruptions in the financial markets and to support home financing, we took action to address the situation at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Federal Reserve also acted to prevent the disorderly liquidation of the insurance company AIG. And in coordination with central banks around the world, the Fed has injected much-needed liquidity into our financial system.

These were targeted measures designed primarily to stop the problems of individual firms from spreading even more broadly. But more action is needed. We must address the root cause behind much of the instability in our markets — the mortgage assets that have lost value during the housing decline and are now restricting the flow of credit. America’s economy is facing unprecedented challenges, and we are responding with unprecedented action.

Secretary Paulson, Chairman Bernanke, and Chairman Cox have briefed leaders on Capitol Hill on the urgent need for Congress to pass legislation approving the federal government’s purchase of illiquid assets, such as troubled mortgages, from banks and other financial institutions. This is a decisive step that will address underlying problems in our financial system. It will help take pressure off the balance sheets of banks and other financial institutions. It will allow them to resume lending and get our financial system moving again.

Additionally, the federal government is taking several other steps to address the trouble of our financial markets.

The Department of the Treasury is acting to restore confidence in a key element of America’s financial system — money market mutual funds. In the past, government insurance was not available for these funds, and the recent stresses on the markets have caused some to question whether these investments are safe and accessible. The Treasury Department’s actions address that concern by offering government insurance for money market mutual funds. For every dollar invested in an insured fund, you will be able to take a dollar out.

The Federal Reserve is also taking steps to provide additional liquidity to money market mutual funds, which will help ease pressure on our financial markets. These measures will act as grease for the gears of our financial system, which were at risk of grinding to a halt. They will support the flow of credit to households and businesses.

The Securities and Exchange Commission has issued new rules temporarily suspending the practice of short selling on the stocks of financial institutions. This is intended to prevent investors from intentionally driving down particular stocks for their own personal gain. The SEC is also requiring certain investors to disclose their short selling, and has launched rigorous enforcement actions to detect fraud and manipulation in the market. Anyone engaging in illegal financial transactions will be caught and persecuted [sic].

Finally, when we get past the immediate challenges, my administration looks forward to working with Congress on measures to bring greater long-term transparency and reliability to the financial system — including those in the regulatory blueprint submitted by Secretary Paulson earlier this year. Many of the regulations governing the functioning of America’s markets were written in a different era. It is vital that we update them to meet the realities of today’s global financial system.

The actions I just outlined reflect the considered judgment of Secretary Paulson, Chairman Bernanke, and Chairman Cox. We believe that this decisive government action is needed to preserve America’s financial system and sustain America’s overall economy. These measures will require us to put a significant amount of taxpayer dollars on the line. This action does entail risk. But we expect that this money will eventually be paid back. The vast majority of assets the government is planning to purchase have good value over time, because the vast majority of homeowners continue to pay their mortgages. And the risk of not acting would be far higher. Further stress on our financial markets would cause massive job losses, devastate retirement accounts, and further erode housing values, as well as dry up loans for new homes and cars and college tuitions. These are risks that America cannot afford to take.

In this difficult time, I know many Americans are wondering about the security of their finances. Every American should know that the federal government continues to enforce laws and regulations protecting your money. Through the FDIC, every savings account, checking account, and certificate of deposit is insured by the federal government for up to $100,000. The FDIC has been in existence for 75 years, and no one has ever lost a penny on an insured deposit — and this will not change.

America’s financial system is intricate and complex. But behind all the technical terminology and statistics is a critical human factor — confidence. Confidence in our financial system and in its institutions is essential to the smooth operation of our economy, and recently that confidence has been shaken. Investors should know that the United States government is taking action to restore confidence in America’s financial markets so they can thrive again.

In the long run, Americans have good reason to be confident in our economic strength. America has the most talented, productive, and entrepreneurial workers in the world. This country is the best place in the world to invest and do business. Consumers around the world continue to seek out American products, as evidenced by record-high exports. We have a flexible and resilient system that absorbs challenges and makes corrections and bounces back.

We’ve seen that resilience over the past eight years. Since 2001, our economy has faced a recession, the bursting of the dot-com bubble, major corporate scandals, an unprecedented attack on our homeland, a global war on terror, a series of devastating natural disasters. Our economy has weathered every one of these challenges, and still managed to grow.

We will weather this challenge too, and we must do so together. This is no time for partisanship. We must join to move urgently needed legislation as quickly as possible, without adding controversial provisions that could delay action. I will work with Democrats and Republicans alike to steer our economy through these difficult times and get back to the path of long-term growth. Thank you very much.

Statement by Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson

The President will speak at 10:45 AM. I’ll send his remarks soon after he has spoken. Here’s what Secretary Paulson said shortly after 10 AM this morning.

Last night, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, SEC Chairman Chris Cox and I had a lengthy and productive working session with Congressional leaders. We began a substantive discussion on the need for a comprehensive approach to relieving the stresses on our financial institutions and markets.

We have acted on a case-by-case basis in recent weeks, addressing problems at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, working with market participants to prepare for the failure of Lehman Brothers, and lending to AIG so it can sell some of its assets in an orderly manner. And this morning we’ve taken a number of powerful tactical steps to increase confidence in the system, including the establishment of a temporary guaranty program for the U.S. money market mutual fund industry.

Despite these steps, more is needed. We must now take further, decisive action to fundamentally and comprehensively address the root cause of our financial system’s stresses.

The underlying weakness in our financial system today is the illiquid mortgage assets that have lost value as the housing correction has proceeded. These illiquid assets are choking off the flow of credit that is so vitally important to our economy. When the financial system works as it should, money and capital flow to and from households and businesses to pay for home loans, school loans and investments that create jobs. As illiquid mortgage assets block the system, the clogging of our financial markets has the potential to have significant effects on our financial system and our economy.

As we all know, lax lending practices earlier this decade led to irresponsible lending and irresponsible borrowing. This simply put too many families into mortgages they could not afford. We are seeing the impact on homeowners and neighborhoods, with 5 million homeowners now delinquent or in foreclosure. What began as a sub-prime lending problem has spread to other, less-risky mortgages, and contributed to excess home inventories that have pushed down home prices for responsible homeowners.

A similar scenario is playing out among the lenders who made those mortgages, the securitizers who bought, repackaged and resold them, and the investors who bought them. These troubled loans are now parked, or frozen, on the balance sheets of banks and other financial institutions, preventing them from financing productive loans. The inability to determine their worth has fostered uncertainty about mortgage assets, and even about the financial condition of the institutions that own them. The normal buying and selling of nearly all types of mortgage assets has become challenged.

These illiquid assets are clogging up our financial system, and undermining the strength of our otherwise sound financial institutions. As a result, Americans’ personal savings are threatened, and the ability of consumers and businesses to borrow and finance spending, investment, and job creation has been disrupted.

To restore confidence in our markets and our financial institutions, so they can fuel continued growth and prosperity, we must address the underlying problem.

The federal government must implement a program to remove these illiquid assets that are weighing down our financial institutions and threatening our economy. This troubled asset relief program must be properly designed and sufficiently large to have maximum impact, while including features that protect the taxpayer to the maximum extent possible. The ultimate taxpayer protection will be the stability this troubled asset relief program provides to our financial system, even as it will involve a significant investment of taxpayer dollars. I am convinced that this bold approach will cost American families far less than the alternative – a continuing series of financial institution failures and frozen credit markets unable to fund economic expansion.

I believe many Members of Congress share my conviction. I will spend the weekend working with members of Congress of both parties to examine approaches to alleviate the pressure of these bad loans on our system, so credit can flow once again to American consumers and companies. Our economic health requires that we work together for prompt, bipartisan action.

As we work with the Congress to pass this legislation over the next week, other immediate actions will provide relief.

First, to provide critical additional funding to our mortgage markets, the GSEs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will increase their purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS). These two enterprises must carry out their mission to support the mortgage market.

Second, to increase the availability of capital for new home loans, Treasury will expand the MBS purchase program we announced earlier this month. This will complement the capital provided by the GSEs and will help facilitate mortgage availability and affordability.

These two steps will provide some initial support to mortgage assets, but they are not enough. Many of the illiquid assets clogging our system today do not meet the regulatory requirements to be eligible for purchase by the GSEs or by the Treasury program.

I look forward to working with Congress to pass necessary legislation to remove these troubled assets from our financial system. When we get through this difficult period, which we will, our next task must be to improve the financial regulatory structure so that these past excesses do not recur. This crisis demonstrates in vivid terms that our financial regulatory structure is sub-optimal, duplicative and outdated. I have put forward my ideas for a modernized financial oversight structure that matches our modern economy, and more closely links the regulatory structure to the reasons why we regulate. That is a critical debate for another day.

Right now, our focus is restoring the strength of our financial system so it can again finance economic growth. The financial security of all Americans – their retirement savings, their home values, their ability to borrow for college, and the opportunities for more and higher-paying jobs – depends on our ability to restore our financial institutions to a sound footing.

More oil supply

In May of 2007, I wrote Why are gas prices high, and what can we do about it? At the time, the national average price for a gallon of regular unleaded gasoline was $3.22.

The national average price is now 59 cents higher, at $3.81 per gallon. That’s down 30 cents from a high of $4.11 in early July.

In June of 2007, here’s what I wrote.

Q: So what can the government do about [high gas prices]?

A: In the short run, almost nothing. In the long run, the President has proposed to:

- lower demand by increasing fuel economy standards (“CAFE”), and also to reform the way those standards are measured, to encourage sound science, safety, and keep costs low

- increase our domestic oil supply by drilling for more oil, both in the Gulf of Mexico and off the Alaskan and Virginia coasts (these are already underway), and in Alaska (we need Congress to change the law)

- increase our supply of alternative fuels by expanding something called the Renewable Fuel Standard, mandating that more of our fuel come from ethanol (from corn and, eventually, other plant sources), and expanding it to include other alternatives like electric vehicles, plug-in hybrids, and coal-to-liquids

- increase our insurance policy by doubling the size of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The SPR is a few big holes in the ground where the nation stores oil, just in case there’s a severe supply disruption

- and, most importantly, encourage the development of new technologies on both the supply side and the demand side. The President has proposed increased federal R&D funding for cellulosic ethanol, batteries and plug-in hybrid vehicles, and even a “Hydrogen Fuel Initiative”in the long run.

#1, #3, and #4 are the President’s new “20 in 10” proposal that he rolled out in the State of the Union address this year. Together, they would reduce our gasoline usage by up to 20% within 10 years (by 2017). If you want to learn more about our “20 in 10” energy proposal, you can find a good description here.

The solutions take years to have a big effect. We’re urging the Congress to take those long-term actions now. It’s taken years to get to this point, and it’s going to take us years to work our way out of it. But that’s no excuse for not starting now.

What has happened since June of 2007?

- The higher fuel economy standards (#1) are now law. The President signed them into law in December of 2007.

- The expanded Renewable Fuel Standard (#3) is also now law. It was enacted in the same December 2007 bill.

- Congress has increased federal R&D funding for cellulosic ethanol, batteries, and hybrid vehicles (#5).

The two things the Congress has not done are:

- increase our domestic oil supply;

- increase our insurance policy by doubling the size of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. In fact, they have moved in the opposite direction, by stopping the fill of the SPR.

On June 18th of this year the President proposed that Congress take four steps to expand American oil and gasoline production:

- Lift the legislative bans to drilling on the Outer Continental Shelf, off our coasts.

- Lift a legislative ban preventing firms from developing onshore oil shale resources.

- Lift a legislative ban preventing environmentally responsible drilling in 2000 acres of the Alaska National Wildlife Reserve (less than .01% of the ANWR area).

- Create an expedited process for resolving legal disputes around energy projects, and establish the Secretary of Energy as a “Federal Coordinator” with authority to establish deadlines and ensure the timely review of Federal, state and local permits needed to undertake refinery projects.

We released a policy memorandum at the time that described in more detail each of these four steps.

At the time, the President offered to lift an Executive Branch prohibition on drilling in the Outer Continental Shelf when Congress acted on #1. A month later, Congress still had not acted, so the President lifted the Executive Branch prohibition.

It’s now August recess for Congress, and they still have not acted. Some House Republicans have remained in Washington, however, and are protesting Congressional inaction by giving speeches on the House floor even though Speaker Pelosi has turned off the CSPAN cameras and the microphones. They’re bringing in constituents and tourists and speaking to them about the need for increased domestic energy production.

This past Tuesday, the President again called on Congress to lift the legislative ban on drilling on the Outer Continental Shelf:

Members have now had an opportunity to hear from their constituents, and if they listen carefully I think they’ll hear what I heard today, and that is a lot of Americans from all walks of life wonder why we can’t come together and get legislation necessary to end the ban on offshore drilling. And so today I join House Republicans in urging the Speaker of the House to schedule a vote on offshore oil exploration as soon as possible.

Now, the way ahead is this: The moratorium on offshore drilling is included in the provisions of the Interior appropriations bill. When Congress returns, they should immediately bring this bill to the House floor and schedule an up or down vote on whether to lift the moratorium on offshore drilling. Our goal should be to enact a law that reflects the will of the overwhelming majority of Americans who want to open up oil resources on the Outer Continental Shelf.