Jobs Day January 2010

Here is your key data:

- The U.S. economy lost a net 85,000 jobs in December 2008.

- The unemployment rate held constant at 10.0%.

- Average weekly hours held constant.

I will show you my two favorite employment graphs, then give some thoughts about the intersection of the economics and the politics. This report was more important politically than it was economically. As always, you can click on a graph to see a bigger version.

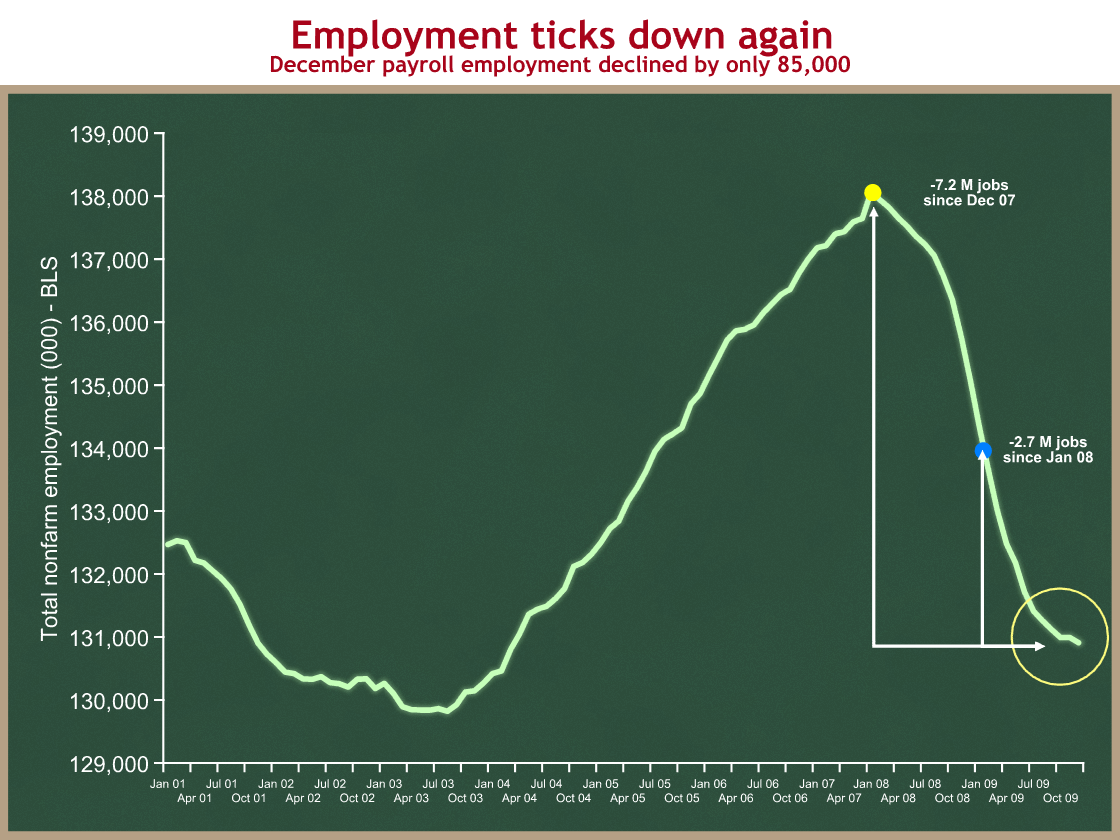

I’m going to show you employment levels. Most others show you changes in levels. If you look inside the yellow circle you can see the -85,000; it’s the downleg at the very end of the graph, after the little flat part. That difference between flat and downward is what has everyone nervous. They are trying to figure out whether it will be flat in the near future as a prelude to going up, or whether last month’s downtick represents a continuation of the longer term downward trend.

One thing I like about this graph is it helps me keep perspective. In this case, one bad data point does not make a new trend, but then again, maybe the recent flatness was an anomaly. If we see a similarly-sized job loss next month, then I’ll get worried. Until then, for me yesterday’s report is an “uh-oh,” rather than an “oh no.”

The other useful feature of this graph is it shows how deep of an employment hole we’re in. The economy needs to create 2.7 M net new jobs to return to the employment level when President Obama took office (this is politically but not economically significant), and 7.2 M net new jobs to return to the high point of December 2007. Since the population and potential labor force are always growing, we need the economy to create even more than 7.2 M net new jobs to return to full employment.

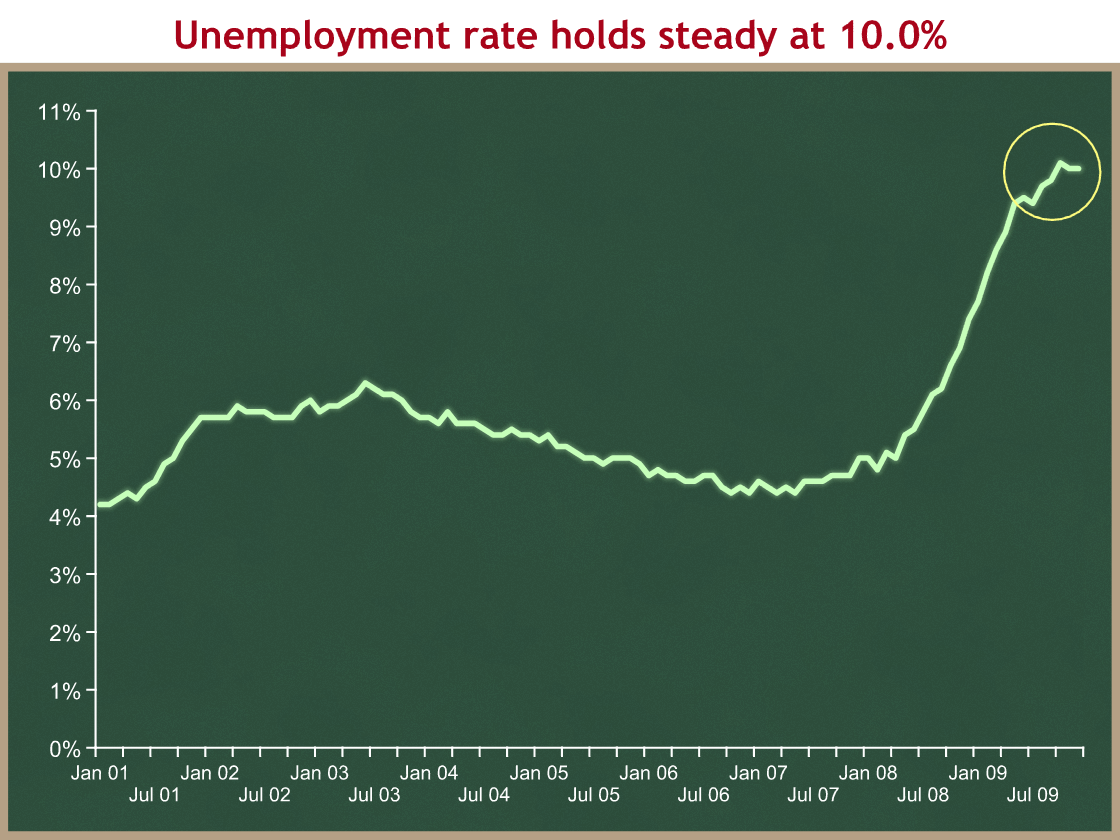

Now let’s look at the unemployment rate.

Inside the yellow circle you can see the rate holding steady at 10.0%. Economists I trust use 5.0% as their rule-of-thumb for full employment. Respectable experts seem to cluster in the 4.8 – 5.5 range. Whatever point you pick as full employment, we have a long way to go.

Together these graphs appear to tell a story of a very weak job market that is not yet improving. Please remember that the debate on CNBC and on the editorial pages focuses on the direction of the graph within the yellow circle, and does not pay enough attention to the huge employment gap between where we are now and where we’d like to be. Both are important.

The President’s comment yesterday reinforces my point:

Job losses for the last quarter of 2009 were one-tenth of what we were experiencing in the first quarter. In fact, in November we saw the first gain in jobs in nearly two years. Last month, however, we slipped back, losing more jobs than we gained, though the overall trend of job loss is still pointing in the right direction.

He’s accentuating the positive (which is fine) comparing the downward slopes of two segments on the first graph, and saying that the recent downward slope is much more gradual than the earlier one. He’s right, but that’s only part of what matters. It’s still going down, which is bad, and, equally importantly, even when it starts going up, we have a long hill to climb.

Politics

If anyone looks back at what the President and his team have said in prior months, they’ll see evidence of touting one month increases and ignoring one month decreases. It is politically risky to run out and take credit after only one good month. You need to let a positive trend build before drawing conclusions about the future. This is hard to do in a White House, especially when you have been waiting a long time for good news.

As we bounce around zero net change, the politics of the +/- sign are far more significant than the number. There is little economic difference between, for instance, +25K jobs and -25K jobs, but the political difference is enormous. Today’s bigger minus sign puts the Administration and its allies on economic defense in the political fray. They are trying to argue that things are improving and their policies are working, but they have to point to a longer term slowing of the decline, overlooking the continued decline, last month’s bad data, and the huge employment gap. They’re actually right that the economy isn’t declining anywhere nearly as rapidly as when the President took office, but that’s not really saying much. I think they are overstepping when they try try to frame slower declines as good news.

If you’re a political junkie, the past few weeks are a tremendous example of why American politics is so fascinating. On December 24th, everyone in Washington knew that January would be focused on the health care conference, a slowly but steadily improving economic picture, and a new focus on the budget deficit. In less than three weeks the political narrative has been transformed. It is now about a terrorist threat and intelligence failures, an economy that may be weakening again, Democratic retirements and party switches, and, oh yeah, finishing health care conference and a new focus on the budget deficit. From the White House perspective, all of these changes were exogenous. They are forces to which the President and his team must now adapt.

I’ll bet that State of the Union draft looks quite different than it did three weeks ago.

What question should I ask four bank CEOs?

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission has its first substantive hearing next week. The hearing will begin Wednesday morning (details to follow when they’re public). The commission staff has told the press we will have a panel of four financial CEOs/Chairs:

- Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs;

- Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase;

- John Mack of Morgan Stanley; and

- Brian Moynihan of Bank of America.

I expect each will provide a written statement and some oral testimony. Commissioners will then ask questions. There will be other panels as well, which I will discuss after the Commission staff makes the details of them public.

I am one of 10 commissioners, and there are four people on this panel, and several panels, so I anticipate I will get to ask at most three or four questions, and more likely one or two. I assume I can submit written questions as well.

I am posting to ask for suggestions: what do you recommend I ask these men about the causes of the financial crisis?

I am serious about this request. I was a policy staffer for 14 years and have written hundreds (thousands?) of hearing questions and answers for my former bosses, so I have a few good questions in mind. At the same time, I long ago learned the value of getting input from a wide range of sources, so here’s your chance.

In return, I ask that you take this seriously. Here is how you can best help me.

Please post your question in the comments or email it to me: kbh <dot> fcic <at> gmail <dot> com. Warning: I will impose a stricter comments policy on this post, and I intend to delete comments which stray from the parameters described below.Please take your rants elsewhere, and post or send me only serious questions that meet these criteria.

Please do:

- Suggest questions that are appropriate to ask a firm CEO or Chairman. These are general managers who think about their firm as a whole. Questions should be about the forest or at least big trees, not about leaves and twigs.

- Suggest questions that can elicit information that is not otherwise available but should be.

- Suggest hard questions.

Please don’t:

- Suggest questions designed only to attack or embarrass the witnesses. I won’t ask them. My goal is to elicit information and analysis and, if possible, to encourage debate and discussion of what happened and why. I have no problem asking questions that embarrass witnesses or that they want to avoid, but only if it’s the most effective path to serious policy debate. I will leave the demagoguery to others.

- Send me speeches. I am interested in asking questions that solicit useful answers, not in hearing myself talk. If your question begins Don’t you think … then you’re on the wrong track.

The Commission’s mission is to “submit on December 15, 2010 to the President and to the Congress a report containing the findings and conclusions of the Commission on the causes of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.”

To repeat: We’re supposed to understand and explain the causes of the current financial and economic crisis. That should guide your questions.

While I will consider questions on any topic related to our mission, when thinking about large financial institutions, I am most interested in questions surrounding the too big to fail concept. I am also quite comfortable asking prospective questions about how well-prepared we are to prevent the next crisis, whatever that may be.

If all goes smoothly, within the next day or so I will post again with similar requests for other panels and witnesses. My goal would be to post again before next Wednesday with the best questions I have received.

To help get your thinking started, here is the key text from the invitation letter sent to the CEOs by Commission Chairman Phil Angelides and Co-Chairman Bill Thomas. This is already circulating widely among DC insiders and lobbyists, but the public doesn’t have access to it. That’s unfair. Having it will also help explain the written and oral testimony you see from the CEOs next week, since you will know the questions to which they are responding.

These are good questions, but they do not necessarily reflect my thinking, so please do not feel you need to limit the questions you suggest to the scope described below.

The FCIC is interested in learning what caused financial problems experienced by your company, including losses incurred, and what changes have been implemented as a result. Therefore, your testimony should address the following topics:

- What were the primary errors and business practices that caused the financial problems at your company and what actions have been taken to address them;

- What were your company’s business models and major sources of income (or loss), what changes have been made, what were the reasons for the changes, and what are your company’s current business models and sources of profit;

- What types of lending activities did your company pursue that caused the financial problems, including the amount, Iypes and terms of loans being made, what changes have been made, what were the reasons for the changes, and what are your company’s current lending practices;

- What were the risk management policies and practices at your company, including the types of investments being made, underwriting and approval of investments including reliance on third parties for due diligence, monitoring of investments by management, the board of directors, committees of the board of directors, and any other persons or entities, and the accounting and public reporting of the company’s investments. What changes have been made to your company’s risk management policies and practices, what were the reasons for the changes, and what are your company’s current risk management policies and practices. In addition, what were your company’s risk exposure, what changes have been made to your company’s risk exposure, what were the reasons for the changes and what are your company’s current risk exposure;

- What were the executive compensation plans and practices at your company and how did they contribute to the problems. What changes have been made to your company’s executive compensation plans and practices, what are the current executive compensation plans and practices, and what were the reasons for the changes.

I look forward to your suggestions, and want to thank everyone who has emailed me input for my work on the commission. Please keep it coming, using the same email address provided above. I am sorry I can’t respond to everyone who is sending me stuff … the volume is just too great.

(photo credit: Empty hearing room by talkradionews)

Health care projections for the new year

Now that the House and Senate have passed remarkably similar health care bills, what is the probability that the President signs health care reform this year? 75%? 95%? 99%?

It’s high. Very high. I am struggling with this question, and at the moment estimate 85%-90%. This may be shaded low by wishful thinking, but I think there is more uncertainty than most in Washington might assume.

Everyone likes it when I pick a specific number, but I think it’s more useful for me to explain the forces that I think will drive success or failure. Policymaking and legislating is always dynamic, and it’s far more useful if I share some tools that can allow you to make your own assessment. At a minimum, you can be a well-informed observer of (or participant in) the process as things change over the next several weeks.

I oppose this bill. I would prefer a very different kind of reform to current law, and, as flawed as it is, would prefer current law to the bills that have passed the House and Senate. Nevertheless, I will here use “success” to mean the President signs a law, and “failure” to mean he does not.

Factors contributing to likely legislative success

I will list the most important factors first. The ranking is important.

- The House and Senate have each passed remarkably similar bills. Sure there are high-profile differences, but these bills are overwhelmingly similar. The differences are small relative to the change either bill would make to current law. These are huge bills, but substantively they’re not that far apart.

- 219 House Democrats (and one Republican) and 60 Senate Democrats have already voted aye on final passage of one of these bills. For each of these Members, the easier path is probably to vote the same way they did last time. Changing to a no vote means they have to explain their flip. Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid and their whips can think of their vote-counting exercise as “How many votes do we lose from 220/60 we have if we do X,” rather than “How do we build up to 218/60 votes.” I assume the overwhelming majority of the House and Senate Democratic caucus can be taken for granted as an “aye” vote, assuming the substance ends up somewhere between the two bills. (No member would ever admit that their vote is independent of substance, of course.)

- The President must have a signing ceremony, especially given a weak economy, exploding deficit, a new terrorism issue breaking against him, and three recent Democratic retirements or flips. It’s fairly clear that the White House will do whatever is necessary to achieve that goal. They have a lot of resources and tools they can bring to bear.

- The President has indicated his support for both bills, and will presumably support any compromise that can pass both Houses. The binding constraint is therefore 218 & 60, not any particular policy element, allowing the Leaders tremendous policy flexibility they need to get votes. It also means the conference report will likely have even more warts than either the House or Senate-passed bills.

- The President, his staff, and both Congressional Leaders are clearly indicating that the window is open. Hint for reporters: don’t just look at the deals inserted into this bill. Look for White House commitments that are executed outside of this legislation. Look for press releases from Members of Congress about particular projects, hospitals, or other spending opportunities in their district. There can be several different types of deals made by the White House and Congressional leaders to secure a Member’s vote:

- a change to a health policy element of the bill (e.g., how much should we pay rural hospitals, or what size construction firm should be exempted from the employer mandate);

- targeted spending in the bill (e.g., Nebraska’s Medicaid FMAP giveaway, special treatment for Blue Cross / Blue Shield, or provisions targeted to provide funding to specific hospitals, each of which will be somewhat cleverly and disguised with inscrutable legislative language);

- targeted spending outside the bill (e.g., we’ll build that bridge in your district using funds already appropriated in other laws);

- unrelated policy commitments (e.g., a rumor that the Congressional Hispanic Caucus might back down from their demand that the bill cover illegal aliens, if the President commits to push immigration reform within a certain timeframe);

- political commitments (e.g., the President or VP or First Lady will come to your district and do a policy event or a fundraiser).

- The President has at least twice demonstrated his ability to rally Members of his party to be more flexible and cooperative, in his early September speech, and in a more recent closed door meeting with Senate Democrats. The President’s poll numbers are soft, but Members of his party will still follow his lead as best they can. Even Democrats who need to vote no want the President to succeed, and no Democrat will want to be the swing vote who prevents the President from getting 218 or 60. This means direct pressure by the President, through phone calls and Oval Office meetings, should be quite effective.

- Outside liberals appear split into three factions: (1) support the agreement, whatever it is; (2) move it left now, but then support whatever they come up with; and (3) kill the bill. As long as outside liberals are not unified in (3), Congressional Leaders probably don’t have to worry about a revolt from liberal Members. Governor Dean’s opposition is less effective than it was 3-4 weeks ago.

- The President and Congressional Leaders have smartly avoided creating a new deadline and have lowered timing expectations. They have explicitly rejected the State of the Union as a deadline and are signaling that a deal may be possible in February. While this eliminates an opportunity to pressure their Members with an artificial deadline, it also means they cannot fail to make a deadline that doesn’t exist.

Factors contributing to possible legislative failure

Again, I will list the most important factors first.

- The vote margins are razor thin. If two House Democrats or one Senate Democrat believe their previous aye vote will cost them their seat this November, there could be a huge problem. The average level of support among Democratic members is irrelevant. What matters is how the most nervous Members who previously voted aye will vote. Speaker Pelosi has little margin for error. Leader Reid has none.

- (Democratic) Members are back home in their States and districts. We have no idea what they are hearing from their constituents. Will any of these Members return to DC and feel they need to “correct” their previous aye vote? We know that national polling says these bills are unpopular, but what matters is the direct pressure felt by Members from their constituents, and how that pressure affects the behavior of those Members. There was a huge tidal effect in August, which the President stemmed with his early September speech. Now I think it is the biggest and most important unknown.

- Why are they moving so slowly? Friends are telling me there is little serious work being done this week, even at the staff level. This gets harder the longer it takes, because interest group influence and outside political pressure have time to build and force Members to make demands: “I can vote aye only if you do X.”

- When Congress left town by December 24th, health care was maybe #3 on the Washington/national issue agenda, behind economy/jobs and the deficit. In less than two weeks, terrorism and Democratic retirements have reshaped the Beltway narrative, pushing health care down further. This is quite unusual, and it’s astonishing that reshaping 1/6 of the economy isn’t the top agenda item, but that appears to be the developing inside-the-Beltway reality. I think that makes it slightly harder to pass a bill, but it could push in either direction.

- Congressional Republicans have been surprisingly energized and effective. Their attacks have to a large extent shaped the public debate. I remember when most Republicans were afraid to talk about health care. That is no longer the case. Their greatest assets are their intensity, the breadth of participation from their Members, and the strength of their policy arguments. They have been far more effective than I had anticipated, especially given how outnumbered they are. If they continue applying intense pressure over the next 3-6 weeks, they may be able to affect the outcome.

- Even if they don’t, Congressional Republicans and their outside allies appear to be building toward a long-term strategy. The stimulus was a Presidential victory last February that has since been redefined to be a policy question mark and a political minus for its supporters. These health bills start from a much weaker policy and political starting point, and if Republicans and their outside allies continue to pound away even after a signing ceremony, there will be long-term policy and political effects that are now impossible to predict. Nervous Congressional Democrats should worry that their opponents will highlight this issue in November, and implementation foul-up stories are ready-made for ongoing press coverage. This is reinforced by policies which front-load the tax increase pain and don’t deliver subsidies for several years. I won’t go so far as to say that this will be a reenactment of the repeal of the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of the late 80s, but the seeds are there.

- CBO is now well-established as a scorekeeper and referee. This is the one area where the policy can be determinative, because the Leaders need a “good” CBO score to hold votes.

If the Speaker and Leader Reid were in town for the next two weeks aggressively driving this process forward, I would estimate a 99% chance that they succeed. But their apparent slow pace, razor thin vote margins, the shifting macro agenda, and the uncertainty about Member feedback make the President’s legislative success less than certain. Betting on a signing ceremony is still a smart wager, but I’d take 7:1 odds against.

(photo credit: Christopher Chan)

Senator Dorgan’s retirement

Senator Byron Dorgan (D-ND) is retiring. In almost eight years as a Senate staffer, I spoke with him only two or three times. I know that I cannot think of a time when I agreed with something he said on economic policy. His prairie populism is a completely different perspective from my own.

It’s because I so often disagree with him that I think it’s important I pass along this story from a friend. This friend has economic policy views similar to my own, and at the time he worked for a Republican Senator:

I’ve always had a soft spot for Senator Dorgan because of one incident on the Senate floor. He and my boss were in a big policy argument on the Senate floor, and I had some charts printed up and things kept going wrong with the graphics – I scratched out some last-minute fixes and the new blow-up was hastily delivered to me on the floor – I took a cursory look at it to be sure the fixes were made, they were, and I put it up behind my boss.

So my boss is going to town, just tearing into Senator Dorgan’s argument, and Senator Dorgan comes over and whispers to me “Those numbers on your poster just can’t be right.” And as he’s telling me how, I look at the board and yes indeed – they had screwed up the dates on the bottom of the chart. Somehow they’d gone back to an earlier version of the chart that had a different timeline on the bottom. What should have been decade by decade was labeled as year by year.

I wanted to fall through the floor. I told Senator Dorgan he was right, slipped a note to my boss telling him the chart was wrong, and awaited the further public humiliation.

Senator Dorgan went back to his place and did a vigorous rebuttal to my boss – and conspicuously didn’t mention the error on our chart. He could have made us look idiotic – he didn’t.

Sort of thing a staffer never forgets.

I tip my hat to Senator Dorgan, a vigorous and honorable advocate for views with which I strongly disagree.

(photo credit: Wikipedia)

Understanding conference and ping pong

My sources are confirming the new conventional wisdom that Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid are working to “ping pong” the health bill rather than go to conference. I think it might be helpful to work through the mechanics of both paths.

I will describe the ping pong and conference floor procedures, then what typically happens behind the scenes. I will also provide a little analysis of the current situation. Today’s post is about explaining the process. I will follow up tomorrow with an update of my projections for health care reform.

Updates to reflect technical corrections and updated intel are in green.

Ping pong procedure

The formal term is “messages between the Houses.” This is procedurally far simpler than a conference. In practical terms for this bill, here’s what I would expect.

On December 29th, the Senate sent the bill it passed on Christmas Eve to the House. A new amendment to that bill will be negotiated by Democratic Congressional leaders, Committee Chairs, and the President’s staff. I expect Speaker Pelosi, Leader Reid, and their staffs will be the most important players in these negotiations.

The House will then try to pass a rule that brings up the Senate-passed bill, makes one amendment (the negotiated agreement) in order, and passes the bill with the new deal as an amendment. I would expect three two votes after the amendment is negotiated, and the Speaker will need to hold a majority of the House for each vote. (Technically, the House would “move to concur with the Senate bill with an amendment.”)

That bill will then be sent to the Senate. Leader Reid can, at his discretion, move to proceed to the “House message” (think of it as the House-passed bill containing only the new negotiated agreement). That House-passed bill is then debatable and amendable in the Senate. This means Leader Reid would need 60 votes to (a) block additional amendments and (b) shut off a likely Republican filibuster. I assume Leader Reid would block Republican amendments by a procedural move called filling the amendment tree, then file cloture on the House-passed bill. The Senate would take up to three at least two votes: a majority vote on the motion to proceed to the House message, a 60-vote cloture vote two days after the Senate process began, and a majority final passage vote the day after that. In addition, there will likely be points of order available against the bill (message) in the Senate. At least one of these could require 60 votes to waive.

So you have six at least five votes:

- A House floor vote on the rule.

- A House floor vote on the amendment (“the deal”).

- A House floor vote on final passage: the House “agrees with an amendment to the Senate amendment.”

- (maybe) A Senate vote on the motion to proceed to the House-passed bill (the “House message.”)

- A Senate vote on cloture (needs 60).

- A Senate vote on final passage (needs 51).

The important and hardest votes are #2 and #5.

Conference floor procedure

On Christmas Eve, the Senate passed H.R. 3590, containing the text of the Reid amendment as modified by a month of debate, as the Senate version of the bill.

Had Leader Reid tried to go to conference, he would have had to offer three motions, in sequence. They are:

- I move the Senate insist on its amendment [to the House-passed bill];

- I move the Senate request a conference with the House on the disagreeing votes of the two Houses; and

- I move that the Chair be authorized to appoint the following conferees on the part of the Senate [ list Senators ].There is then a fourth step that can be introduced by any Senator:

- The Senate can vote to instruct its conferees to do X, where X is any policy matter.

Usually, the first three motions are combined and done by unanimous consent in about eight seconds. On a highly controversial bill, a single Senator can insist that the Senate debate and vote on each motion. Since these are debatable (but not amendable), they can be filibustered. This means that Minority Leader McConnell could force Majority Leader Reid and the Senate Democrats to invoke cloture (with 60 votes) three times before getting to conference. When you include the three votes on the motions, this means up to six votes (three of which require 60) and several days of floor time.

Difficulty #1 for Leader Reid would be holding 60 votes repeatedly. It would be far easier than the Christmas Eve vote, but it’s still a political hassle for his nervous members, and it’s a procedural hassle for Leader Reid to bring his members back for these votes. That sounds absurd, but it’s a real concern for a Leader — getting the attendance when your Members have made other plans is hard.

Difficulty #2 for Leader Reid comes from the opportunity for unlimited and politically painful motions to instruct from the minority. The unlimited part means Republicans could stretch this process out forever (theoretically). The politically painful part is at least as serious Republicans could easily draft amendments designed to split Democrats and make closed-door negotiations more difficult. (e.g., How can the Senate include the House provision to raise marginal income tax rates when the Senate adopted a motion to instruct that rejected such a policy on a 75-25 vote?)

Once the motions to instruct are complete, the Senate message would then go to the House. The House would have to vote on and adopt three parallel motions. That is presumably easier in the House because they’re only majority votes. Once the House has gone to conference with the Senate, a 30-day clock begins. When that clock expire, the House minority has the ability to force a vote on a motion to instruct, causing Speaker Pelosi similar headaches to those faced by Leader Reid.

Once there is a conference agreement (more on this below), one body (probably the House?) would take up the conference report and try to pass it. Assuming the House passes it, that is then sent to the Senate. The motion to proceed to the conference report would be privileged and could not be filibustered. The text could not be amended, but it could be filibustered. So Leader Reid would need 51 votes to proceed to the bill, 60 votes to invoke cloture on it, and a majority to pass it. After that, it would go to the President for his signature.

Behind the scenes

Conference is a more formal and structured way to reach an agreement, and often has a greater chance of building support for the final passage floor votes. The structure creates legitimacy and somewhat reduces the ability of opponents to claim the final product is arbitrary. To the extent that the conferees appointed by the Leaders represent the political breadth of their caucuses and the various factions involved, it’s easier to sell the final product. For instance, if Rep. Stupak, Rep. Lowey, and Sen. Nelson were conferees, and if the three of them negotiated an abortion compromise, the Leaders might be able to more easily sell that deal to both sides of the abortion debate (within the Democratic caucus).

Most bills are done through a conference process. The Leaders typically appoint as conferees the relevant committee chairmen (and ranking minority members), other senior members of the relevant committees, and other key players whom they view as instrumental to a deal. So it’s easy to imagine Speaker Pelosi including someone like Rep. Stupak as a conferee, or Leader Reid including Senators Nelson and/or Lieberman as conferees. You bring them inside the tent and give them leverage over the writing of the conference report, buying yourself their support on the back end when that conference report comes to the House and Senate floors.

In a conference situation, much of the negotiation is done committee-to-committee. Since I assume Republicans will be entirely cut out of the closed door negotiations, in a conference I would expect Ways & Means Committee Chairman Rangel, Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus, and their staffs to negotiate the tax title of a conference report. The leaders and other conferees don’t have to agree to a Rangel-Baucus negotiated tax title, but there would be a strong presumption to use that negotiation as the basis for further discussion. Similarly, in a “normal” conference you would expect House Commerce Committee Chairman Waxman, House Education and Labor Committee Chairman George Miller, and Senate HELP Committee Chairman Harkin to take the lead in negotiating an agreement on the insurance “reforms.”

The Leaders (Pelosi, Boehner, Reid, and McConnell) rarely appoint themselves as conferees. When they do, they almost never make themselves the “chair” of their conferees. A conference structure naturally keeps power in the hands of the committee chairman (and ranking members, when the minority isn’t cut out). The leaders have enormous influence, but that influence is indirect. That difference can hugely affect the outcome.

Ping pong (messages between the Houses) is the opposite. Power lies entirely in the hands of the Speaker and Leader Reid, each of whom unilaterally controls the text that will be brought to the House and Senate floor. The Speaker tells the Rules Committee Chairman “I want a rule on this bill text,” and hands the Chair the text. Similarly, Leader Reid controls the Senate’s negotiations with the House.

Others, including otherwise powerful committee chairs, have no formal power in this scenario. A smart leader will of course involve them quite heavily in negotiating and drafting the leader’s amendment, but this shift in formal power greatly weakens the committee chair’s ability to force or block certain policy outcomes.

But with great power comes great responsibility. Ping pong concentrates the power in Pelosi and Reid’s hands, but it also imposes a greater burden on them to deliver the floor votes. Committee chairs (and others who might otherwise have been potential conferees) may be slightly less enthusiastic to sell the final product if they feel it’s not “theirs.” And the free-for-all nature of the closed door negotiations, and the lack of a formal conference structure, can make the leaders’ management task of the negotiation process much more difficult. Structure can make it easier for you to say no when you need to. When everything appears to be at the Leader’s or Speaker’s discretion, then squeaky wheels are rewarded. This creates an incentive for Members to squeak loudly.

Analysis

All indications are that Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid intend to ping pong the bill. Further, it appears many House Democrats (and, importantly, key House Democratic staff) are resigned that this will not be an equal strength negotiation. I do not expect the negotiations will be about finding reasonable compromises or midpoints between the House-passed and Senate-passed bills, the usual starting assumption for a conference. Instead, the Senate’s weakness and no-room margin create enormous strength for the Senate in its negotiations with the House, especially in a less structured ping pong environment.

I instead expect that the Senate bill will form the basis for negotiations. Key House Democrats, including the Committee chairs and their staffs, will try to convince Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid to accept certain components of the House bill. But the burden of proof will be on he or she who wants to make changes to the bill we know can get 60 votes in the Senate. That’s the primary binding constraint.

There will be exceptions to this default assumption. Not every detail of the Senate bill is vote-determinative, no matter what the Senate says. Negotiators will have lots of room for flexibility on important details, especially when those details are important policy but not in the headlines every day. And when Speaker Pelosi is convinced that she must have a policy change to hold 218 House votes, she’ll probably get it.

Playing ping pong works when you have strong leaders in the House and Senate who share a common goal. Speaker Pelosi’s authority and power within the House Democratic Caucus is indisputable, and so for her this strategy makes a lot of sense. I’m less certain about whether Leader Reid would have been better off with a conference, but it appears the path has been chosen. I think a conference is generally the right and more legitimate process, especially for such a complex and important bill. Even given my opposition to the underlying policy, I think they would create a less-worse version of it were they to use a conference. But from a results-oriented standpoint, the Democratic leaders appear to have made a rational process choice, particularly given the Obama-Pelosi-Reid unity, their clear willingness to be flexible on any policy element so they can get to a signing ceremony, and the Speaker’s overwhelming dominance over her caucus.

(photo credit: Ping Pong Peking by foxxyz)

When the pocket veto conflict mattered

Yesterday I described a Constitutional conflict that the President’s Executive Clerk deftly avoided last week. This process was Constitutionally important, but since it was about a superfluous continuing resolution, the underlying substance was trivial. A few former White House colleagues reminded me of a case when this conflict had a real effect on policy.

At the end of 2007, Congress passed the annual Department of Defense Authorization bill. That bill contained an amendment by Senator Lautenberg to allow victims of the Pam Am 103 terrorist attack (over Lockerbie, Scotland) to go after Libyan financial assets in the United States. The provision was drafted broadly, however, and it also would have subjected Iraqi financial assets in the United States to a high legal risk. After the bill had passed but before being presented to the President, the Iraqi government reached out to tell the Administration that this was a huge problem. Administration lawyers agreed that the risk to Iraqi financial assets was real, and that it would be reasonable to assume they might have to withdraw all their financial assets from the U.S. if it became law. No one in the Legislative or Executive Branch had anticipated this, but it was too late. The bill had already passed both Houses of Congress.

A feisty internal Administration Situation Room debate resulted in a recommendation that the President veto the bill over the excess breadth of the Lautenberg amendment. DOJ lawyers then explained that the bill could not be vetoed because the Congress had already adjourned. Well, then we’ll just pocket veto it, the group (almost) concluded, leading to further explanations of why a pocket veto might provoke the Congress to challenge in court the Constitutionality of the pocket veto. The pocket veto-return veto dispute between the Legislative and Executive Branches posed a serious risk to American foreign policy.

President Bush’s advisors did not want the Constitutional conflict, and certainly not in a fight about Iraqi assets in the U.S., where it wasn’t clear whether Congress would fight us because of the underlying policy question.

After ruining the Christmas vacations of several senior Administration officials with a seemingly endless series of conference calls within the Administration and with Congressional leaders, the President’s advisors finally settled on a pocket veto with protective return. They chose this path only after being reassured by Congressional Republican leaders that they would produce the votes, if necessary, to sustain a return veto in the face of a possible override attempt. Here’s the memorandum of disapproval, our public statement, and the press briefing.

Congress did not attempt to override the veto (or accepted the pocket veto, depending on your perspective), and instead passed a new bill in January, which was the text of the old bill minus the broad version of the Lautenberg language. Iraqi assets were not affected by the new law. The President’s team dodged both the bad policy outcome and the Constitutional conflict. By the fall of 2008, there was legal progress on the Pan Am 103 front and Libya set up a victims compensation fund, leading Congress to revoke the remainder of the Lautenberg amendment.

Thanks to Dan Meyer, Deb Fiddelke, and Brent McIntosh, who helped me with this post. Each of them, and many others, lost some of their 2007 Christmas vacation to solve this problem.

Avoiding a Constitutional conflict

While you were preparing for your big New Year’s Eve party, the President’s Executive Clerk was deftly avoiding a Constitutional conflict. The effect isn’t earth-shattering, but I think it’s a fascinating example of how our Constitution works in practice. Consider this a lesson in your graduate course of How a Bill Really Becomes a Law (or doesn’t, in this case).

On December 30th President Obama vetoed his first bill. Before the annual appropriations bill to fund the Department of Defense was enacted into law, Congress had passed a “Continuing Resolution” (CR) to provide funding for continued Pentagon operations. Once the Defense approps bill had become law, the CR was no longer needed. So the President prevented it from becoming law by vetoing it. To my knowledge there was no policy dispute about the need to do this – everyone agreed that the CR was superfluous.

But how the President vetoed it is interesting, if you care about the details of how the Constitution works in practice.

To understand the conflict and how it was avoided, you need to understand how a “normal” veto and a pocket veto work.

First you need to understand how a “normal” veto works, usually called a return veto:

- The bill is passed by both Houses in identical form. This is the engrossed bill.

- The engrossed bill is then enrolled: the House (or Senate) Clerk assembles the actual parchment copy, which is then signed by the Speaker of the House (Pelosi) and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate (Byrd). For this example let’s assume the House Clerk.

- The House clerk then sends the enrolled bill to the President. Someone from the House Clerk’s office gets in a car and drives the bill to the White House and gives it to the Executive Clerk who works for the President. The technical term is that the bill is presented to the President. (“Presented” is in Article I, Section 7 of the Constitution.)

- The President decides to veto it.

- He instructs his Executive Clerk to return the bill to the originating House of Congress (in this case, the House of Representatives) “with his objections.” In this case the Executive Clerk returns it to the House Clerk, with a Memorandum of Disapproval from the President.

- The Congress can then try to override his veto (if they so choose). To do so they need 2/3 of the House and 2/3 of the Senate to override the veto.

The cool part of a return veto is that the President doesn’t ever have to see or touch the actual bill papers. There’s no veto stamp, and he doesn’t sign the memorandum of disapproval. He can do it all by phone. His Executive Clerk can handle the paperwork without the President’s signature.

This contrasts with the traditional process for signing a bill into law, for which the President must physically have the bill in front of him. This sometimes involves putting a staffer onto a plane to transport the bill to him (say, to Hawaii) before the 10-day deadline expires.

OK, let’s turn to a pocket veto. Here’s the relevant sentence, again from Article I, Section 7 of the Constitution:

If any bill shall not be returned by the President within ten days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the same shall be a law, in like manner as if he had signed it, unless the Congress by their adjournment prevent its return, in which case it shall not be a law.

So the President doesn’t (normally) even have to sign a bill for it to become law, although he almost always does. The tricky part comes when Congress had adjourned. Let’s use the CR as our example:

- The House passed the CR (House Joint Resolution 64) by voice vote on Wednesday, December 16th. It passed the Senate by unanimous consent on Saturday, December 19th.

- On Saturday, December 19th, the House Clerk enrolled the CR and presented it to the President.

- The House adjourned for the year on December 23, and the Senate on December 24th.

- The 10-day clock expires on December 31st, since you don’t count Sundays. If the House is adjourned then to “prevent its return,” then the bill does not become law and we say the President has “pocket vetoed” the bill.

Now that we understand both a return veto and a pocket veto, let’s look at the Constitutional conflict. Please note that when I say “Congress” below, I am talking about the institutions of the Legislative Branch – the House and the Senate. Partisanship is in this case irrelevant. This conflict is about tension between the Legislative and Executive Branches of government, not between Republicans and Democrats.

Here’s the sentence again, which the relevant section in bold:

If any bill shall not be returned by the President within ten days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the same shall be a law, in like manner as if he had signed it, unless the Congress by their adjournment prevent its return, in which case it shall not be a law.

Q: If the House of Representatives adjourns but leaves the House Clerk in town, does this “prevent the return” of a bill and mean the President cannot pocket veto it?

When the Constitution was young, there were long periods when Congress was not in session, so there was no one to receive a returned bill and convene Congress for a veto override vote. This was the birth of the pocket veto.

The Legislative Branch view is that the House of Representatives has appointed the Clerk of the House to act as its agent to receive Presidential messages. Since the House Clerk and Secretary of the Senate are always around, there is always a way for the President to return a bill with a resolution of disapproval, even if Congress has adjourned. Thus the Legislative Branch view is that a pocket veto is no longer possible. There’s an exception to this for when Congress adjourns sine die, meaning at the end of a Congress, which happens late in every even-numbered year. But the Legislative Branch view is that intrasession pocket vetoes are no longer possible, since the President can return a bill even when Congress has adjourned for several weeks (say, during August recess or at the end of an odd-numbered year).

The Executive Branch view is that even if the House of Representatives appoints its Clerk as its agent to receive an objected bill, the House Clerk is not the House, and the Constitution requires the bill to be returned to the House, not to an agent of the House. If the House has adjourned, then Congress has by their adjournment prevented the return of the bill, and the pocket veto is operable.

These different views create a risk that an intrasession Presidential pocket veto might be challenged by the Congress in court. Congress might argue in court that the CR (for example) became law after 10 days, even though the President did not sign it. That would be a silly policy outcome, but the Constitutional dispute can and should be separated from the policy question of what the bill would do.

The Executive Branch would rather not provoke this fight, so they use a belt-and-suspenders approach. The President pocket vetoes the bill and he return vetoes it. The President pocket vetoes the bill and does not sign it into law during the 10 days allowed him by the Constitution. He also returns it to the originating body of Congress (in this case the House) with a statement of his reasons for disapproving it “a return veto.” The President’s statement says that he is pocket vetoing it (the Executive Branch view), and he takes all the steps necessary to return veto it. The term of art is a pocket veto with protective return.

MEMORANDUM OF DISAPPROVAL

The enactment of H.R. 3326 (Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2010, Public Law 111-118), which was signed into law on December 19, 2009, has rendered the enactment of H.J.Res. 64 (Continuing Appropriations, FY 2010) unnecessary. Accordingly, I am withholding my approval from the bill. (The Pocket Veto Case, 279 U.S. 655 (1929)).

To leave no doubt that the bill is being vetoed as unnecessary legislation, in addition to withholding my signature, I am also returning H.J.Res. 64 to the Clerk of the House of Representatives, along with this Memorandum of Disapproval.

BARACK OBAMA

THE WHITE HOUSE,

December 30, 2009.

The result: the Legislative and Executive Branches agree that the bill has been vetoed, but for different reasons. The Congress says the bill has been return vetoed. The Executive Branch says the bill has been pocket vetoed. Since both agree the bill has been vetoed, there’s no opportunity for a court challenge.

Conflict avoided.

Kudos to the President’s Executive Clerk Tim Saunders for his many years of service to six Presidents. Kudos to the New York Times’ Peter Baker, the only MSM reporter I can find who wrote about this. And thanks to Brent McIntosh, former White House Deputy Staff Secretary, for once again teaching me how the Constitution works in practice. Thanks also go to another former colleague for his help.

If you found this post interesting, here is a description of how vetoes work here when things get fouled up: A messy end to a bad farm bill.

Happy New Year.

(photo credit: Bill Walsh)

The Real West Wing Tour Guide

Here is a small Christmas gift for you: The Real West Wing Tour Guide (circa 2007).

While the general public can often get a White House East Wing tour through the office of their Member of Congress, West Wing tours can only be given by White House staff.

Through most of President Bush’s time in office, staff were allowed to give tours Tuesday through Friday evenings, and also on weekends.

One summer (I think it was 2003) my West Wing colleague Krista Ritacco and I thought it would be helpful and fun to create a written tour guide for staff. We could improve the quality and accuracy of information and generally help make tours better for both the visitors and the tour guides.

We recruited Krista’s intern, then-Duke University student Sarah Hawkins, to research and write the first version. We then produced simple decks of index cards which we distributed to friends and colleagues on the White House staff. They quickly became an underground hit and were frequently used on tours.

The project went through several iterations, the last quasi-public version of which was developed by Ashley Hickey.

Karen Evans came up with the idea of upgrading it from index cards to a more professional appearance. This is the version you see below, produced by Karen Evans, Tony Summerlin, and the Touchstone Consulting Group on a volunteer basis without using taxpayer dollars. We never distributed this version broadly, even to other White House staff. The contents are identical to the last “public” version, but this version looks even better.

I am distributing this under a Creative Commons License – you can distribute, share, and display this, but you must attribute it, you may not edit it, and you may not use it for commercial purposes.

I expect that today’s West Wing is somewhat different, especially in the displayed artwork and decor. Nevertheless, I hope you find this interesting and enjoyable.

Merry Christmas. Please click on the cover below to see the Guide. If you get an error message, please update your version of Adobe Acrobat Reader. And thanks to those submitting errata in the comments.

My foggy legislative crystal ball

I tried to update my projections for health care legislation but found I was making wild guesses. This is too much of an inside game for me to predict what will happen over the next ten days. My crystal ball is foggy.

I can, however, offer some questions and observations for you to consider. I hope you find them useful.

Q: Is there a deal?

A: We don’t know. We know that, at the behest of the President, Leader Reid is dropping both the public option and Medicare buy-in from his amendment. Last week he said the buy-in was a core element of what he asserted was a consensus Senate Democratic deal. I think there is an Obama-Reid-Lieberman deal on two key issues, the announcement of which generated tremendous legislative momentum. As best I can tell, there is not yet a comprehensive Reid amendment supported by 60 Senators.

Watch closely for reports of a CBO score. Every time I read “Leader Reid’s staff continues to work with CBO,” I think “They still don’t have an amendment.” They need a good answer from CBO, and they need to sell it to 60 Senators. Despite the apparent enormous shift in public momentum favoring Senate passage, it appears they don’t have either one at the moment.

A friend astutely observed, “The proponents of this thing are simultaneously closer to final success – and to a complete collapse – than they have been for months.”

Q: Why might this take until Christmas Eve?

A: Assume Senate Republicans (or at least one) are willing to use all available procedural tools to slow this down. Leader Reid needs three votes: his new amendment to the Reid substitute, the Reid substitute, and final passage. On each of those votes he will need to invoke cloture. That process takes 3+ days.

Example:

- Leader Reid offers his new amendment today and files cloture on it.

- The Senate votes on cloture the day after tomorrow (Saturday).

- Assuming cloture is invoked, there are then 30 hours of debate post-cloture.

- So the new amendment would then be adopted Sunday.

These cloture votes can be “stacked,” but the three 30-hour periods must run sequentially, burning up the entire next week. Then again, Leader Reid may decide he only needs to win one or two of the three before sending everyone home.

In addition, I assume Senate Democrats have figured out that Senate Republicans can offer and force votes on certain amendments during those three 30-hour periods. There could be some politically very difficult votes for Democrats next week.

Update: Two friends point out that Leader Reid can use a tactic called “filling the [amendment] tree” to block consideration of troublesome amendments, so Senate Republicans may lack this opportunity.

Q: Is there really only one legislative option?

A: No, there are two. Option one is that 60 Senate Democrats/Independents can rally around, invoke cloture on, and pass a Reid amendment. House Democrats would then either have to swallow it whole by passing it without a conference, or, more likely, have a conference in which they make some optical tweaks, then swallow it whole. When one legislative body credibly says “We cannot pass anything but X,” and the other says “We don’t want to pass anything but Y,” X wins.

Option two is for the House to initiate a new bill through the reconciliation process. This path could produce a bill that is farther left than the current bill. Both the public option and a Medicare buy-in would survive the Senate’s Byrd rule, although other parts of the bill might be in some jeopardy. Leader Reid could pass such a bill with 50 Senate Democrats plus the Vice President, allowing/forcing up to 10 moderate or nervous Senate Democrats to vote no. I assume House Blue Dogs would similarly vote no. Social issues within the bill would likely move left as well.

If the President, Speaker, and Senate Majority Leader had agreed to pursue this path months ago, it would have had a high probability of legislative success, in a take-no-prisoners fashion. Successfully executing this process now would be less certain because of the calendar and deterioration of broad-based public support for the policies. Outside advocates on the Left would be initially ecstatic, but Leaders correctly fear that further delay and starting over risk implosion. In addition, they appear to want get health care done so they can shift their focus to the weak employment picture and deficit problem. I would be stunned if the leaders chose to go the reconciliation path, despite the pounding they are beginning to take from their Left. Then again, there’s an outside chance they may be forced down this path.

Q: Who are the key decision-makers?

A: Surprisingly, it’s the leftmost Senators and House members. Any single Democratic Senator has the unilateral ability to force the reconciliation path, simply by saying no to Reid’s deal, if and when it comes together. Formally, Leader Reid gets to decide what will be voted on, and he therefore can “box in” either the left or right side of his party. He appears to be following the President’s lead, leaning toward Lieberman on his amendment, and putting liberals in the position of “Are you going to kill health care reform because it doesn’t have everything you want?”

The question then becomes, will one or more Senate liberals reply, “I’m going to vote against cloture on your amendment because I want to force you to either move your amendment back toward me, or to pursue the reconciliation path, which would be long and painful and risks complete failure but, if successful, is more likely to produce a bill that I prefer.”

Similarly, will the President and Speaker be able to hold a large bloc of House liberals on a bill in which Senator Lieberman’s preferences trump theirs? Or will they instead force their leaders to start over?

There’s no question which path the Leaders should prefer. This is instead a test of how these liberal members weigh their policy goals and pleasing their most active supporters, versus team play and supporting their President and party. Outside Lefties would be more effective if they pounded on their liberal friends in Congress who are more likely to be responsive to their pleas. While liberals beat up Senators Nelson and Lieberman, I wonder why they are not challenging Senators Boxer, Rockefeller, and Sanders for not standing up to their party leaders? Each of them has the ability to force the path the Left desires.

It’s not uncommon for legislative leaders to disappoint the average member of their party to satisfy the marginal member whose vote is needed for passage. In this case, however, the left margin has precisely as much leverage as the right. Senator Lieberman demonstrated his willingness to deny the President and risk Democratic party opprobrium to kill a bill he thought was bad. It worked for him. Will any liberal Members of Congress be willing to do the same? Or do they think that a law without a public option and Medicare buy-in is better than forcing another round of internal Senate negotiation, and better than risking a reconciliation path that might lead to complete legislative failure?

I usually think of policy and political spectrums as lines from Left to Right. We talk about “centrists” and people on the “wings.”

Occasionally the line becomes a circle, in which the Left and Right ends start to sound alike, or to have common interests. I can see two cases of that now.

- Outsiders on the far Left and, it appears, all Congressional Republicans now want to kill Leader Reid’s deal (again, if such a deal exists). Outsiders like former Governor Howard Dean and commentator Keith Olbermann argue the Reid plan is too weak, and should either be moved further left or pursued through reconciliation. Either way, they oppose the Reid-Lieberman agreement.

Senate Republicans are similarly firing away. Dean/Olbermann want the Reid-Lieberman plan to fail so they can get something better. Senate Republicans want it to fail because they think the whole bill may crater if it does. These two factions share a goal of killing the Reid-Lieberman deal primarily because they have different expectations about what would happen afterward if they succeed. And Senate Republicans who are slowing the legislative process down may buy time for outside advocates on the Left to encourage/persuade/force Liberal Members of Congress to block the new Reid-Lieberman deal. - Some on the Left now oppose the individual mandate. (See both partsof Keith Olbermann’s commentary.) This surprised me before I understood the logic. Mandating coverage in which the government can “keep prices down” through fiat is a good thing, they argue, while mandates without “cost controls” is bad. This appears to hinge on an intense hatred for a private insurance industry. So now both ends of the policy spectrum oppose the individual mandate within the Reid bill, albeit for different reasons. It would be interesting to see how a vote to strike the mandate turned out in one of the post-cloture voting periods.Advocates on the Left are correct that health insurers would be big financial winners in this bill. The government would be forcing everyone to buy their product, under penalty of punitive taxation for those who did not. Continued support (or at least non-opposition) from the insurers tells me they believe these guaranteed customers are worth the downsides of community rating and premium taxes.

What to watch

- When does Leader Reid have a CBO score? Each day of delay hurts his chances of success.

- After the next Senate Democratic caucus meeting, what do rank-and-file Democrats on the two edges of the party say? (Nelson, Lincoln, Lieberman, Rockefeller, Boxer, Sanders)

- When does Leader Reid lay down (offer) his amendment and file cloture on it? Once he does, he’s committed. Does he do this before knowing he has 60 votes?

- What does Speaker Pelosi say after the Reid amendment has been filed? She has to worry about dynamics within her own caucus.

- Can the White House tamp down outside opposition from the Left before Reid offers his amendment? Does that opposition grow or subside over the next several days?

(photo credit: Crystal Ball #1 by just.Luc)

Updated health care reform projections

Updated projections

I am lowering from 50% to 35% my prediction for the success of comprehensive health care reform. I now think the most likely outcome is a much more limited bill becomes law.

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the House and through the regular Senate process with 60, leading to a law; (was 30% -> 30%)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the House and through the reconciliation process with 51 Senate Democrats, leading to a law; (was 20% -> 5%)

- Fall back to a much more limited bill that becomes law; (was 15% -> 45%)

- No bill becomes law this Congress. (was 35% –> 20%)

My last update was 3 1/2 weeks ago, right before the motion to proceed was adopted. My prediction then that “there is zero chance a bill makes it to the President’s desk before 2010” has been proven correct. At the time that was not an uncommon prediction, but it was inconsistent with what the White House, Speaker Pelosi, and Leader Reid were all saying.

I still believe that if a comprehensive bill becomes law, I anticipate completion in late January or February, with the latter more likely.

In mid-November I wrote,

I would expect that as the third week approaches, Reid would begin to signal that the Senate has worked hard on the bill and needs to bring debate to a close. Around the middle of week three, he would file a cloture motion on his substitute amendment, with the cloture vote happening on or near Friday, December 18th.

Public and private sources suggest this is likely to play out as predicted.

New prediction: I think Leader Reid will not invoke cloture before Christmas. What’s harder to figure out is whether he’ll even try.

Analysis

I’m still stuck on my “two equally strong stories” model:

- It appears the President’s private meeting last Sunday with Senate Democrats had a similar effect to his September Address to Congress. He unified them, rallied them, and generated tremendous team spirit and legislative flexibility. It appears that 60 Senators agree that they need to agree on something, and are willing to bend a lot to reach their common legislative goal. No one of those 60 Senators wants to be vote #41 against cloture, and they’ll give up a lot to avoid that situation. The internal caucus politics and vote counting leads me to believe there’s a 90% chance that cloture will be invoked.

- But the substance of the Reid amendment, and especially his public option “deal,” are in big trouble. The bill is weakening substantively and politically every 2-3 days. On the substance and politics of this particular amendment and deal, I think there’s a 90% chance that cloture will fail.

The question then becomes which force dominates. At the moment, I think it’s the substance, and therefore I think cloture will fail pre-Christmas. Senate Democrats want to agree on something, but no reasonable something yet exists for them to agree upon.

To invoke cloture next week, Leader Reid needs all of the following to go his way:

- He needs CBO to come back with a Medicare buy-in premium that isn’t so high that it scares away members.

- He needs 60 members to support the buy-in, despite the Washington Post editorial page and other center-left elites are trashing it.

- He needs the CBO score to not have other problems that scare away his members.

- He needs none of his members to fold to provider pressure, especially from hospitals. I remember that pressure well from my time in the Senate, and it can be intense, especially from home-state hospitals.

- He needs abortion to be resolved such that none of his 60 votes will bolt on cloture. Is it?

- He needs those Democratic senators favoring reimportation who look like they may not get a vote to be willing to support cloture anyway (e.g., Sen. Dorgan).

- He needs nothing else to go wrong.

If any one of the above goes wrong and he loses a single vote, then he cannot invoke cloture.

I think the Achilles heel at the moment is the new Medicare buy-in component of the so-called public option deal. Press reports are that Reid picked five liberals and five moderates to negotiate a compromise. Early last week he proudly announced a deal that was supported by all 60 Senators. It appears, however, that all he had was an agreement among the 60 to not blow up the proposal until seeing what CBO said about it. Even so, there is fraying around the edges of even that tenuous agreement as his staff work behind the scenes with CBO.

I’m going to guess that by mid-week that proposal has imploded, probably due to a combination of:

- CBO saying the buy-in premium is astronomically high and/or there’s a big cost to taxpayers,

- medical care providers (especially hospitals and doctors) pounding on Democratic Senators,

- more attacks from the press elite,

- exacerbated by continued pressure from Senate Republicans, who are attacking the bill’s quantitative effects: higher spending, higher premiums.

Leader Reid raised expectations by asserting there was a deal when there really wasn’t. If the deal collapses, it’s not just a loss of momentum, it’s moving in reverse. Cloture would not be invoked, and the week could end with a partial implosion.